Baptist Christians must dive fearlessly into the white supremacist and pro-slavery histories of their religion and congregations, Camille Loomis Rehnborg said during a webinar hosted by the Baptist History and Heritage Society.

“We need not fear the discomfort we might feel when we learn about Christian arguments for slavery. I would invite us to consider any discomfort as an intercession from God nudging us toward God’s true vision for a redeemed world,” said Loomis Rehnborg, minister of spiritual formation and outreach at First Baptist Church in Greenville, S.C.

Kimberly Ellison

She spoke in response to Baylor University historian Kimberly Kellison’s presentation of her forthcoming book, Forging a Christian Order: South Carolina Baptists, Race, and Slavery, 1696-1860. Due for release in February, the text documents the collusion of Baptist leaders, churches, associations and seminaries in promoting belief in slavery as a religious and social necessity fully supported by Scripture.

Loomis Rehnborg said First Baptist in Greenville has had its own self-searching to do as a church located squarely in the religious, cultural and political context of the period covered in Kellison’s book. “When history is painful or difficult to face, it is OK to feel that pain and difficulty because we confess a God who walks with us through pain and guides us toward new light and restoration.”

During the society’s Jan. 19 “Making Baptist Public History” webinar, Kellison described support for the institution of chattel slavery as the bond between South Carolina Baptists who were otherwise sharply divided over denominationalism and ordained clergy.

Baptists in the southern part of the state, also known as the Lowcountry, heavily favored denominational structures and state associations as instruments for spreading the gospel and producing educated and trained church leaders. Baptists in the Upcountry, on the other hand, largely opposed seminary trained ministers and denominations.

Camille Loomis Rehnborg

But as the 17th century segued into the 18th century, a shared attitude and theology about enslaved people began to gel, Kellison said. “They disagreed over denominationalism … but they adopted a shared vision regarding race and, by the 1800s, regarding slavery. This is the thread that held them together, this affirmation of white supremacy and a strong affirmation of the Christian version of slavery.”

White men and women in the upper and lower regions of the state came to agree that slavery was not a sin if practiced with biblical principles, she said. “This white-constructed model really was key to white Baptist organizational identity in the Upcountry and the Lowcountry.”

That identity was advanced by Lowcountry Baptists who promoted their vision of the faith in Upcountry communities like Greenville. Kellison identified Richard Furman, a Charleston pastor, as a leading voice in the slavery-as-biblical movement.

Furman, the namesake of Furman University, served as the first president of the first nationwide Baptist organization, the Triennial Convention, and became the first president of the South Carolina Baptist Convention.

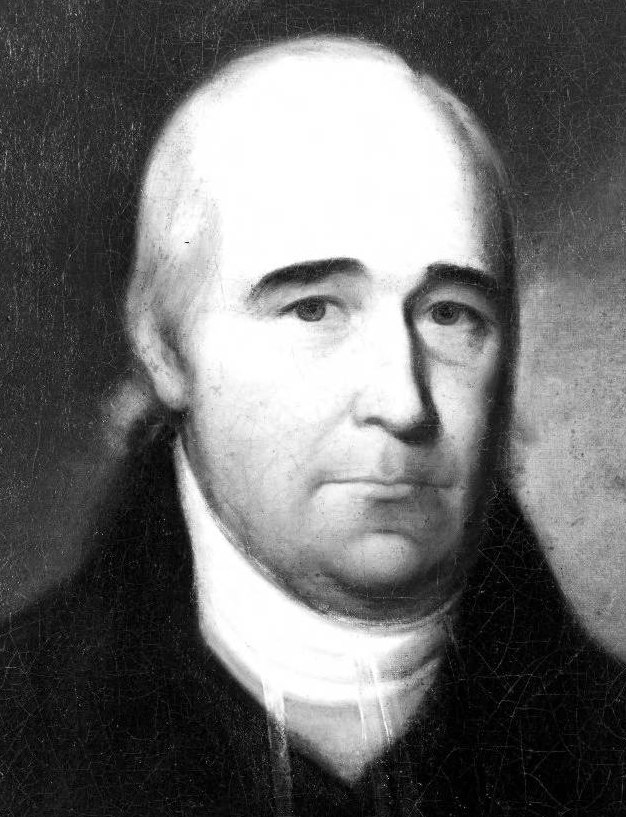

Richard Furman

He also was in the vanguard of a movement for “a white-constructed Christian model of slavery,” Kellison said. “The argument was the enslaver and the enslaved have relative duties to one another. … Within this argument was a clear recognition of racial difference separating the enslaved and the enslaver. The argument that Furman made repeatedly was that Christian slavery would create harmony and order in society rather than create slave insurrections and violence.”

Furman’s pamphlet “Exposition of the Views of the Baptists Relative to the Coloured Population of the United States” asserted that “slavery, when tempered with humanity and justice, is a state of tolerable happiness; equal, if not superior, to that which many poor enjoy in countries reputed free.”

The document, which Kellison displayed, also claimed “a master has a scriptural right to govern his slaves so as to keep them in subjugation; to demand and receive from them a reasonable service; and to correct them for the neglect of duty.”

“No man who is desirous of knowing the will of God and will read the scriptures … can entertain any doubt as to strict propriety of slaves being held.”

She cited a 19th century statement by a local Baptist association in South Carolina to illustrate how effective Furman’s efforts were. It declared: “We believe that the existence and morality of slavery is so clearly acknowledged in the sacred scriptures that no man who is desirous of knowing the will of God and will read the scriptures … can entertain any doubt as to strict propriety of slaves being held.”

The power of those ideas was felt beyond the state’s borders, she added. “Because of Furman, white South Carolina Baptists were at the vanguard of creating a pro-slavery narrative that would, over time, be widely embraced by white Southerners, both religious and secular.”

Loomis Rehnborg added that the concept of Christian slavery also was perpetuated in the Baptist schools and seminaries established in the South during the 18th and 19th centuries.

“In the minds of the white men discussed in Kellison’s history, orthodoxy meant theologies that maintained the oppressive status quo. The theologies and methods of exegesis … protected white supremacy, protected and ensured the subjugation of enslaved people and ensured domination by the enslaving class — the gentry of white Baptist South Carolina.”

The theology of scarcity that slavery and white supremacy represented in that period of history are clearly visible today, Loomis Rehnborg said. “I see this fear in contemporary replacement theory. White people in Western countries fear that people of color seek to replace the white race by immigration and increased birth rates and fear they are colluding to seize finite power and finite resources that belong to white people.”

Digging into such history on the congregational level can be painful, but also spiritually rewarding, Loomis Rehnborg said.

“The essence of our Christian identity is to recall the past and to see how past events still influence our life and our faith today. The road to 2023 is not paved in gold, especially in Christian history. But any pain, or conviction of guilt or shame, or sense of urgency, does not mean we are doing something bad. Life with God does not insulate us from pain. … In fact, our pain confirms our humanity, which itself is a sacred project.”

Related articles:

Slavery, race and biblical authority: Before we claim the Bible is ‘inerrant,’ let’s confess that we aren’t | Opinion by Bill Leonard

Naming and un-naming: Slavery, schools and the present moment | Opinion by Bill Leonard

What to do if you unearth a history of slavery in your church, college or institution?