Since the former president unwillingly departed the office, his Republican minions have leaned into the ardent racist dog whistles and racial mythologies he employed in trying unsuccessfully to remain in power. Big among these Republican racial tropes is the idea that an academic discipline called Critical Race Theory is actually a dangerously racist ideology rolling over the country and trampling white people underfoot.

Despite the fact almost nobody arguing against it knows what it is, Critical Race Theory has become yet another conservative dog-whistle signaling the virtue of the white race and the inferiority of all others.

Greg Garrett

I will tell you frankly: Although I know what Critical Race Theory is not — a boogeyman that will destroy our nation — I also could not define for you precisely what Critical Race Theory is, as I have not studied it formally or informally. Stephen Sawchuk offers us an origin story in Education Week. Critical Race Theory, he writes, “emerged out of a framework for legal analysis in the late 1970s and early 1980s created by legal scholars Derrick Bell, Kimberlé Crenshaw and Richard Delgado.”

I never have read any of these writers, but at its most basic, it seems that Critical Race Theory acknowledges the reality that America’s history is shaped not only by individual racism but by the formal and informal structures that have put and kept people of color in inferior situations in housing, education, jobs, health care and almost every other aspect of American life.

This feels like simple observation to me, but some senators have labeled Critical Race Theory “activist indoctrination,” and so this factual understanding that American life has been shaped by racist policies designed to keep people who look like me in positions of prominence now has become an issue to those who don’t want to acknowledge their power, position and privilege.

A troll on social media recently responded to a sentiment I’d posted about systemic racism by saying that people like me who dwell in the past are mentally ill, and that I could really benefit from therapy. (That last part is true. I do.)

But what I did not say to my new friend — there really is no point in arguing on Twitter except for the personal satisfaction of believing you are right — is that people refusing to acknowledge that past are living in delusion, or worse, in baleful ignorance.

I am a white, middle-class, middle-aged Christian male. I am well aware that I have benefited from that identity over and over again. I never have felt in danger during a traffic stop, never been in danger in casual encounters with law enforcement, and never ever felt that when I left the house in the morning there was a chance I would not return in the evening based on the color of my skin.

“I benefited and continue to benefit from structures set up generations before me to ensure that I can go all day without having to acknowledge or even think about my skin color.”

I benefited and continue to benefit from structures set up generations before me to ensure that I can go all day without having to acknowledge or even think about my skin color.

On the other hand, the median wealth of Black families in America is 15% that of the median wealth of white families.

The racist mythologies white people have advanced for 400 years in this country justify this tragic inequity by claiming that Black people are lazy, stupid, criminal or simply not as advanced as whites. These racial mythologies are self-confirming, as they lead to more Black people being excluded, red-lined, imprisoned and dumped from public assistance that has been freely given to white people.

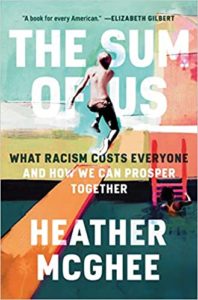

I personally have benefited from an array of what Heather McGhee in The Sum of Us calls the “free stuff” the U.S. government offered to help my family climb into the white middle class and pass on wealth to the next generations: the Homestead Act of 1862, mortgage insurance during the Great Depression (and the ability to simply get a mortgage because we didn’t live in red-lined areas occupied largely by Black families), the GI Bill, Social Security — the list of free stuff that has mostly enriched whites is long.

I personally have benefited from an array of what Heather McGhee in The Sum of Us calls the “free stuff” the U.S. government offered to help my family climb into the white middle class and pass on wealth to the next generations: the Homestead Act of 1862, mortgage insurance during the Great Depression (and the ability to simply get a mortgage because we didn’t live in red-lined areas occupied largely by Black families), the GI Bill, Social Security — the list of free stuff that has mostly enriched whites is long.

Black people often didn’t benefit in the least from these government giveaways, despite racial stereotypes about “welfare queens” and lazy Black men on unemployment. In fact, in recent years, white voters and policy makers have actually chosen to contract the safety net and diminish our social spending — even though the majority of those disadvantaged are poor whites — rather than have people of color benefit from them as well. (As Ryan Sit notes in Newsweek, despite the racist stereotype that Black people leech off the system, “whites are the biggest beneficiaries when it comes to government safety-net programs.”)

McGhee understands how American racism has shaped our unequal economy: “The advantages white people had accumulated were free and usually invisible, and so conferred an elevated status that seemed natural and almost innate. White society had repeatedly denied people of color economic benefits on the premise that they were inferior; those unequal benefits then reified the hierarchy, making whites actually economically superior.”

And all this economic injustice, of course, is without talking about slavery, about Jim Crow, about lynchings, about the destruction of prospering Black communities — none of which people terrified by Critical Race Theory want to own.

How does my recognition that systemic inequities, born of racial prejudices, have made me prosperous and safe at the same time they have impoverished and threatened my Black sisters and brothers make me a racist?

“If Critical Race Theory means we begin to tell the truth about our American experiment, then it provides a much greater good than a delusional denial of our past.”

I don’t know. But if Critical Race Theory means we begin to tell the truth about our American experiment, then it provides a much greater good than a delusional denial of our past, regardless of how many state legislatures (like in my native Texas) tell schools not to tell that truth.

Last year on his Emmy- and Peabody-awarded weekly show Last Week Tonight, John Oliver summed up why I’d rather we lean into Critical Race Theory even if it makes people who look like me uncomfortable: “Ignoring the history that you don’t like is not a victimless act, and a history of America that ignores white supremacy is a white supremacist history of America.”

We’ve told that racist story for way too long, and despite squeals to the contrary, Critical Race Theory is not injecting racism into our schools and public life; it is simply asking that race be considered.

And any angle of vision that helps us tell a new story about America, a truer story, can help us live into the hard work of repair and racial reconciliation to which we are called.

Greg Garrett is an award-winning professor at Baylor University. One of America’s leading voices on religion and culture, he is the author of more than two dozen books, most recently In Conversation: Rowan Williams and Greg Garrett and A Long, Long Way: Hollywood’s Unfinished Journey from Racism to Reconciliation. He is currently administering a research grant on racism from the Eula Mae and John Baugh Foundation and writing a book on racial mythologies for Oxford University Press. Greg is a seminary-trained lay preacher in the Episcopal Church and Theologian in Residence at the American Cathedral of the Holy Trinity in Paris. He lives in Austin with his wife, Jeanie, and their two daughters.

Related articles:

White hysteria, Critical Race Theory, and eyes that dare not see | Opinion by David Gushee

Want to understand Critical Race Theory? Read the Good Samaritan story | Opinion by Susan Shaw and Regina McClinton

It’s not just the SBC banning Critical Race Theory; now state legislatures are joining the fight

Could you win a quiz show by defining ‘Critical Race Theory’? | Analysis by Mark Wingfield