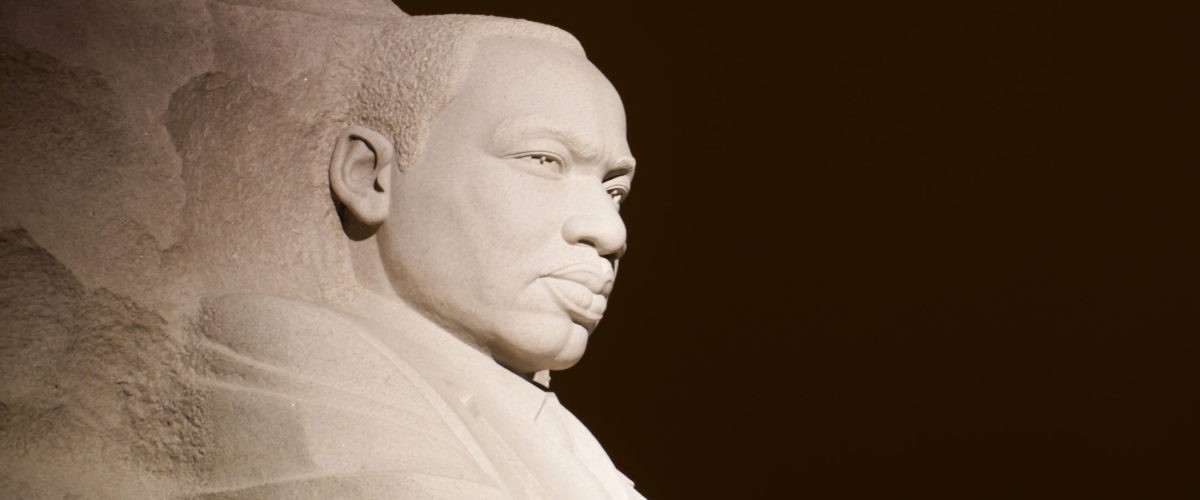

I was in third grade in 1983 when Ronald Reagan, after much hesitancy, signed an act designating the third Monday of each year as a federal holiday honoring the life and contributions of Martin Luther King Jr. I was in seventh grade when Texas, my home state, recognized the holiday which, sadly, occurs every year around the same date as Confederate Heroes Day, which still, in 2021, is an optional paid holiday for many State of Texas employees.

I have no memories of the day being recognized in any official way, and only vague recollections of being taught anything in school about Martin Luther King or the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. Any mention of King by church leaders or other adults I knew was always shaded with airs of suspicion and qualification. “Well, he said some good things, but…,” usually followed by whispers of communism and infidelity, with the implication that we needed to take him with “a grain of salt.”

Craig Nash

When unofficial recognition and observance of MLK Day reached critical mass in the white, evangelical circles I was raised in, we focused almost solely on a narrow selection of quotes from a small handful of speeches but never on the circumstances that gave rise to his oratory. We took a scalpel to every inconvenient part of the narrative. As popular opinion and legal rulings bent toward justice and a recognition of the dignity of all God’s children, white people reserved the right to control and isolate the narrative around King and civil rights. This is a feature of the system, not a bug.

It was a feature at work in the murder trial of George Zimmerman for his shooting of 17-year-old Trayvon Martin. The white judge in that case implored the jury to ignore anything that led up to the altercation, “thus transforming a 17-year-old, unarmed kid into a big, scary Black guy, while the grown man who stalked him through the neighborhood with a loaded gun becomes a victim,” according to Carol Anderson in her essay (and title of a subsequent book) “White Rage.”

In her Introduction to The Fire This Time: A New Generation Speaks about Race,” Jesmyn Ward notes how this selective isolation of details and framing of the Trayvon Martin killing in the court of public opinion gave permission not to see what needed to be seen:

I saw a child. And it seemed that no one outside of Black Twitter was saying this: I read article after article that others shared on Twitter, and no major news outlet was stating the obvious. Trayvon Martin was a 17-year-old child, legally and biologically; George Zimmerman was an adult. An adult shot and killed a child while the child was walking home from a convenience store where he’d purchased Skittles and a cold drink.

“I’ve seen this selective framing in my work addressing systems of poverty and hunger.”

I’ve seen this selective framing in my work addressing systems of poverty and hunger. The median yearly household income in the United States is $66,000 for white families, $51,000 for Hispanic or Latino families, and $42,000 for Black families. Black and Hispanic/Latino families are almost twice as likely to experience food insecurity at any given time than white families. The list of disparities is long.

When I share this data with white Christians, I am almost invariably met with one of two reflexive responses for how to address the issue: We either need more job training or we need to find a way to teach people experiencing poverty and food insecurity how to motivate themselves.

This quick framing is a subtle power move on par with quoting King’s inspiring “I Have a Dream” while ignoring his damning “Beyond Vietnam” speech, or of asking a jury to ignore George Zimmerman’s stalking of Trayvon Martin while focusing only on the moments before the shot was fired. Its purpose is clear: To absolve us of any guilt over the racial disparities in income and quality of life. If the narrative around poverty is “they need to be motivated and trained to work harder,” then we can avoid the reality that the income gap occurs in a world where people of color work at least as hard as their white counterparts.

King spoke of this tendency of ours while addressing white, moderate clergymen in his “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” when he wished that their concern for the racist conditions that led to protests was as high as their concern for protests themselves. He refused to let them take control of the narrative in a way that would absolve them of discomfort. He gave them an opportunity, as we all have the opportunity, to release the reins of control and allow the voices of lived experience to inform and shape our understanding not just of how people become marginalized, but what we must do to ensure that “every valley is exalted, every hill and mountain laid low, the rough places made plain, the crooked places straight, and the glory of the Lord revealed.”

Craig Nash lives in Waco, Texas, and works for the Baylor Collaborative on Hunger and Poverty. He is a graduate of East Texas Baptist University and Baylor’s George W. Truett Theological Seminary. He is active in the life of University Baptist Church in Waco.