In 1936, with war clouds gathering in Europe, author E.B. White wrote the following for The New Yorker: “Shopping in Woolworth’s, in the turbulent days, we saw a little boy put his hand inquiringly on a ten-cent Christ child, part of a creche. “What is this?” he asked his mother, who had him by the hand. ‘C’mon, C’mon,’ replied the harassed woman, “you don’t want that!” She dragged him grimly away — a Woolworth Madonna, her mind dark with gift-thoughts, following a star of her own devising.”

Traditional holiday cheer features extravagant strings of lights, the scent of fresh-cut evergreens, Frosty and Rudolph, frosted-breath carolers, and the squeals of children opening colorfully ribboned presents. Plus It’s a Wonderful Life and Miracle on 34th Street drama.

Ken Sehested

Not to mention the season’s commercial aperitif of Black Friday, Small Biz Saturday, Cyber Monday and Giving Tuesday. And a heavy dose of newscasters’ heart-warming anecdotes of charity events. Lots and lots of charity.

We sometimes forget that charity is one means of maintaining control by the few and a reminder to the many of their dependency.

The original Yuletide accounts, from the Gospels of Matthew and Luke, are more chilling. And not the kind you ward off with your warmest coat, mittens, wassail and hot toddies.

Three cruel stories

This year’s cheer was dampened by three cruel stories (and one alarm) from friends arriving on my computer last week. Gut punches, one after the other.

The first was news from Brazil about my friend, Odja, a pastor and feminist theologian. She received an explicit death threat (that included her children and husband) after having officiated a same-sex wedding. Even more despicable, a photo depicting a gun lying next to a Bible was included. Having spent time in their home, I could visualize browbeaten, anxious looks on all their faces.

Then a note from my friend Shizua,* a theology professor in Japan, who wrote to request additional background information on Mon Saw,* a theology professor in a South Asian country. Shizua was attempting to bring Mon Saw to Japan as a visiting professor but also to provide him with sanctuary from his dictatorial military government’s reach, which considers him a security threat.

I told Shizua the little I knew and gave contact information on someone who knows Mon Saw much better.

“This year’s cheer was dampened by three cruel stories (and one alarm) from friends arriving on my computer last week.”

Then, two days later, Shizua sent a distressed note urging me to delete our email exchange about Mon Saw. She had become aware of cyber snoopers tracking his name.

Next came a note from LeeAnn, a Canadian friend, passing along the distressing news that our common friend, Mirkit*, had become the subject of “red-baiting” rumors in the Philippines, stemming from her faith-based human rights activism. Red-baiting — whispered accusations of being associated with a violent insurgent group — can be the prelude to deathly consequences in the ruthless regime of Filipino President Rodrigo Duterte.

The news just kept on coming. Two friends in a nearby city sent a note requesting various forms of aid to help them prepare to receive an extended family of Afghan refugees being resettled. What a great Advent story! But they also asked that we not broadly publicize this effort because of some loud anti-immigrant voices in the area.

Celebrating the season

Don’t get me wrong. I love festive occasions. Balsam Firs loaded with ornaments, many bearing long family memories. We have a magnificent Moravian star in our front window. We’ve often gone caroling. And powdered sugary Pecan Sandies, an annual treat from our firstborn.

For many years, my family got in the car after dinner, drove through the night, arriving at my parents’ home down the Louisiana bayou just before dawn. It wasn’t visions of sugarplums that kept us going. It was the promise of my Mama’s gumbo.

For the first few centuries of the church’s existence, no one paid attention — or even knew — to a supposed date of Jesus’ birth. It wasn’t until the fourth century that church leaders in Rome established a Christmas holiday, probably to compete with pre-Christian rituals and observances around the Winter Solstice.

Oliver Cromwell

When Oliver Cromwell was crowned in 17th century Great Britain, he vowed to abolish Christmas festivities, as did the pilgrims and Puritans of Colonial America. (The observance was illegal in Boston for a time.) It was the zealously pious who inaugurated the war on Christmas.

In case you need a seasonal primer, I recommend “How December 25 Became Christmas,” by Andrew McGowan.

Good news/bad news

The most enduring lesson I learned in seminary was this: In order to comprehend how, and for whom, the gospel is good news we also must understand how, and for whom, it is bad news. Or as Dietrich Bonhoeffer put it, “The coming of God is truly not only glad tidings, but first of all frightening news for everyone who has a conscience.”

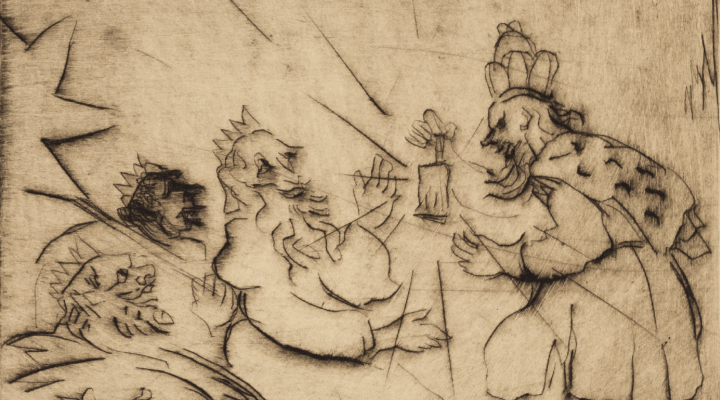

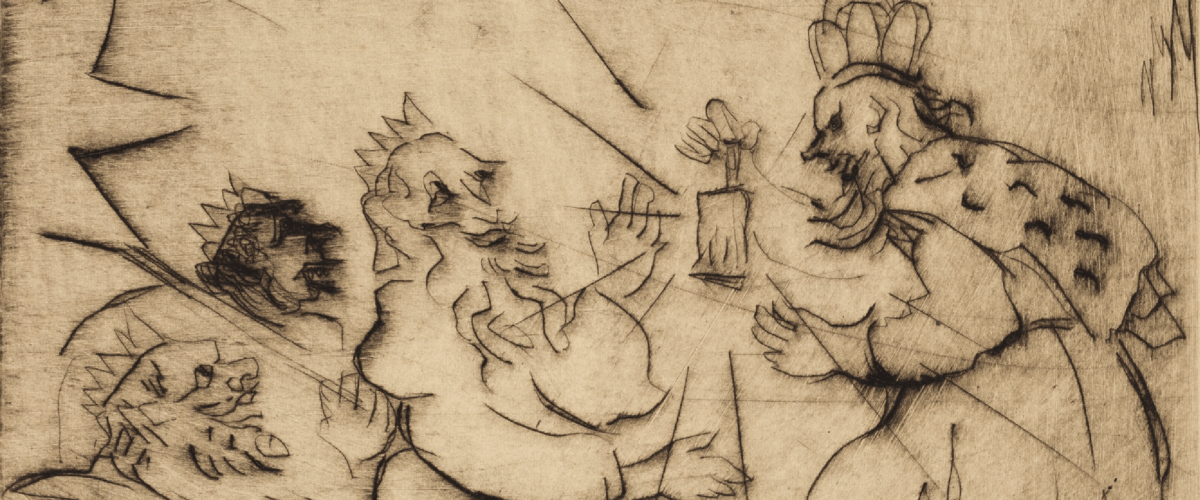

Maybe we need to learn how to put Herod back into Christmas, to pay attention to the subversive lines in Mary’s hymn of praise, maybe incorporate into our liturgical calendar the little-known observance of the Feast of the Holy Innocents (Dec. 28), which is grounded in Matthew’s R-rated tale of horror, of Herod’s henchmen slaughtering male infants in Bethlehem.

“The Massacre of the Innocents,” 1640,

Pacecco de Rosa. Philadephia Museum of Art.

The significance of the Incarnation is this: God is more taken with the agony of the earth than the ecstasy of heaven. This is the meaning of our baptismal vows, reiterated every time we observe Communion.

The way of the world is not threatened by our holiday baubles. The threat implied in our crèches has been expunged. Since no-crying-he-makes, the world’s cries have been silenced in our Nativity transcript.

According to Good Housekeeping, Bing Crosby’s White Christmas is the No. 1 Christmas song. Which, ironically, is a prophetic judgment even today.

Bring back Herod?

So, how to reinstate Herod in the Christmas story — and restore the insurrection intent in the Incarnation’s advent?

It begins with rededicating ourselves to reclamation of the beatific vision of God’s intention embedded in creation’s story, including the Hebrews’ sighs amid Pharaoh’s camp, which Scripture says mobilized God’s attention:

- Heralded in the psalmists’ and prophets’ lament, “How Long, O Lord?”

- Announced in the angel’s reassurance, “Fear not.”

- Underscored in Jesus’ Beatitudes and model prayer.

- Acclaimed in the Apostle Paul’s metaphor of “all creation groaning in labor pains” but destined to be “free from its bondage to decay.”

- And reassured by the Revelator’s vision of a new heaven and a new earth, where all tears will be dried and death will come undone.

Fostering such beatific vision is essential in developing the needed perseverance, in full view of the world’s pain, buoyed by the reliable goodness of the news: We have not been abandoned to enmity. Hope bats last. Joy outlasts all disconsolation. God is calling death’s bluff.

*Names changed to protect identity.

Ken Sehested is curator of prayerandpolitiks.org, an online journal at the intersection of spiritual formation and prophetic action.

Related articles:

Angel wings and devil tails: Meditation on the Feast of the Holy Innocents | Opinion by Ken Sehested

It’s hard to quit Herod, but we must worship another | Opinion by John Insore Essick

Let’s keep Herod in Christmas | Opinion by Brett Younger