Our country is politically torn apart. This is the reality that greets us every day in the national media, regardless of which network, website or newspaper we follow.

Our states are labeled by their Republican or Democratic governors, eliciting opinions that these elected officials do not represent all of the citizens of their states. In Washington, the House of Representatives is dominated by Democrats while the Senate is ruled by Republicans. Congress is waging a fierce battle to secure the ideological high ground in the Supreme Court, one party maneuvering for a controlling majority of justices, the other resisting in order to maintain a closer balance of power. The Department of Justice operates according to what seems to be a partisan agenda, but questions are raised whether its actions would be any more impartial or just if the political power were reversed.

Rob Sellers

At the 2004 Democratic National Convention, Barack Obama — in his keynote speech — declared: “There is not a liberal America and a conservative America; there is the United States of America. There is not a Black America and a White America and Latino America and Asian America; there’s the United States of America.” More familiar is the abbreviated expression of this maxim: “There are no Red States or Blue States, just the United States.”

But this idealistic image of our nation and people no longer inspires many Americans who have taken political sides.

Despite our being deeply troubled by the domestic division that marks our country during this election season, many of us don’t realize that our enthusiasms and loyalties only propagate the problem. Daily, we open social networking sites and are bombarded with political ads, opinion editorials and news reports both real and fake, as well as hundreds of comments and verbal reactions to posts that readers either adored or abhorred.

It is unsettling enough to read snarky, ill-tempered and angry comments from complete strangers, or from people we don’t know well, but a quite different emotion is stirred when good friends or family members attack our positions, challenge our patriotism or question our faith when we disagree.

How many things can’t we talk about?

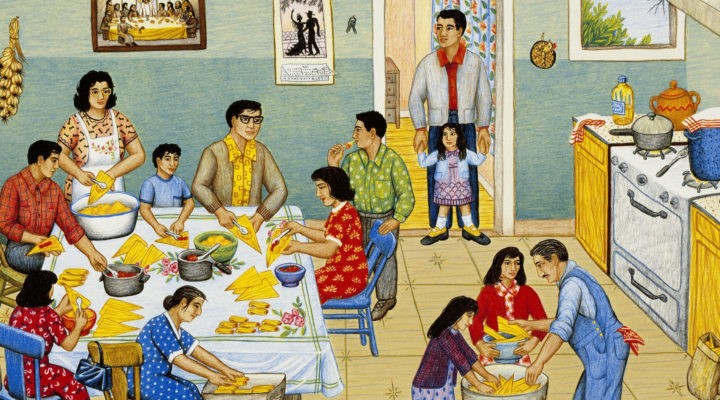

There used to be just two things we shouldn’t talk about at Thanksgiving. Now a Google search reveals multiple lists of five, 10, 15, or even 20 topics to avoid in order not to process acid stomach along with our turkey and dressing. Perhaps holidays should be refuges from the political storm, but at the very moment it might be helpful to hear honest opinions in the safe context of family, we have become so opinionated that respectful dialogue is impossible.

“The childhood rhyme, ‘Sticks and stones may break my bones but words will never hurt me,’ is not now and never was true.”

The childhood rhyme, “Sticks and stones may break my bones but words will never hurt me,” is not now and never was true. Words sting. They cut. They cause unbearable pain and festering wounds. They destroy and even kill.

But hurtful words are not the only danger we are facing today, for acts of violence from every side are becoming frighteningly common.

There are proud “militias” patrolling cities with automatic weapons, standing by to disrupt democratic election procedures, occupy state houses or even conspire to kidnap, try and execute a governor. There are autonomous far-left groups loosely affiliated by their militant opposition to fascism and extreme right-wing dogma and their willingness to use violence, if necessary, to achieve their goals. There are trucked-in, out-of-state agitators infiltrating peaceful protests in order to burn, loot and demolish businesses and public buildings. There are anonymous military-equipped enforcers controlling the crowds with intimidation and fomenting anger and fighting in their camouflaged, unidentified uniforms. There are riot police and federal troops wielding batons and shields to push back marchers, or firing paint balls, tear gas and rubber bullets into fleeing groups of American citizens pursuing their Constitutional right to demonstrate.

Most divided since the Civil War?

Some have been saying for the last few years that America is more divided now than at any time since the Civil War. That is the opinion of professor of policy, government and international affairs at George Mason University, Bill Schneider, who admits that “nothing is ever permanent, but we are broken.”

“This alarming prediction about the threat to our Union’s existence is made by both conservative commentators and liberal ones.”

This alarming prediction about the threat to our Union’s existence is made by both conservative commentators and liberal ones. Could it be that our country is careening down a steep, dangerous path of political disagreement that will lead inexorably to armed insurrection?

In the great and shameful conflict of 1861-1865, alliances were destroyed because of different allegiances. Neighbors were driven by principle, pragmatism and profit to distrust and arm themselves against one another. Siblings enlisted with army units on opposing sides of the fight. Parents and children, sisters, brothers and cousins disregarded what bound them together because their political differences were stronger than their familial love.

North and South was a trilogy of television miniseries by historical fiction writer John Jakes that was situated before, during and immediately after the Civil War. This series related the tragic saga of Orry Main, son of a South Carolina family of slave-owning farmers, and George Hazard, son of a Pennsylvania mill town family of abolitionist manufacturers. Orry and George, former fellow cadets at West Point and good friends, found themselves on different sides of history because of their heritage, beliefs and loyalties that ultimately drove them to fight for opposing armies. Now, more than a century and a half later, with predictions of another civil conflict growing in number, this tragic story symbolizes the fractured nature of our society once again.

Lesson from a grieving family

How can we hope to overcome our current discord and avoid interpersonal, even national, calamity?

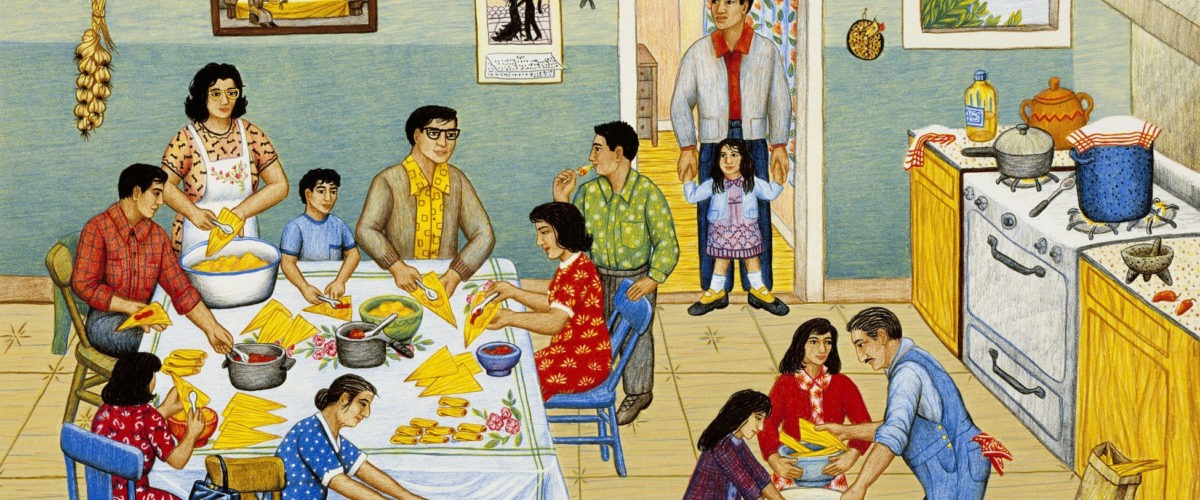

I believe that the love that is expressed in the midst of shared tragedy can overcome even the most dramatic differences. Recently I conducted a graveside service for the beloved parent of my close friends. I was touched by the love that tied the three siblings to one another as they grieved their loss — and their unity was profoundly experienced, despite the likelihood that they do not have identical views about what’s best for our country.

In the midst of shared tragedy, the love they feel for one another was never at risk because of their distinct political views. Perhaps what I observed in this family is a microcosm of what must happen in our larger society. Facing and going through hard times together, people who feel genuine love for one another have a way to overcome their divisions.

“Facing and going through hard times together, people who feel genuine love for one another have a way to overcome their divisions.”

We are facing incredible trials, in fact we are sharing national tragedies — a deadly pandemic and the incalculable loss of life, natural disasters and personal losses caused by climate change, economic collapse that is destroying livelihoods and canceling dreams, racial unrest climaxing centuries of injustice and discrimination, political intrigue and the crumbling of our democracy. Confronting this constellation of challenges, it never has been more true that our love must be greater even than our faith (in our party or candidate) or our hope (in a bright future).

A house divided

Jesus said that a house divided against itself will not be able to stand (Mark 3:25). He prophesied that in the very contentious and disruptive days of his life in Palestine, when so many political perspectives were argued and advanced. I suspect the brother of Jesus must have watched him closely and noted his calm and compassionate demeanor, later writing, “You must understand this, my beloved: let everyone be quick to listen, slow to speak, slow to anger” (James 1:19).

Can we who claim to follow the Man from Galilee listen more, speak less and dispel our anger with love? Is it possible for us to replicate the love we feel for our parents, siblings, children and grandchildren and apply it liberally to our global family, our national family and our human family?

Perhaps what the world needs now really is “love, sweet love.”

Rob Sellers is professor of theology and missions emeritus at Hardin-Simmons University’s Logsdon Seminary in Abilene, Texas. He is the immediate past chair of the board of the Parliament of the World’s Religions in Chicago. He and his wife, Janie, served a quarter century as missionary teachers in Indonesia. They have two children and five grandchildren.

Related articles:

Baptist layman offers lessons from South Africa on overcoming civil war

‘Broken Churches, Broken Nation’: Yes, Pastor Jeffress, words do ‘mean something’