Surely I am not the only person in the land of the free and the home of the classified documents who keeps wishing, even hoping, that the innumerable issues, actions and ideas that divide us as a people have finally hit bottom, that so many terrible, dangerous demons have been unleashed that it can’t get any worse than climate, guns, mass shootings, inflation, politics, elections, government action/inaction, schools, college tuition, Christian nationalism, threatening phone calls. militias, conspiracy theories, church closings, SCOTUS rulings, COVID, monkeypox, polio, sex abuse scandals, disinvited lecturers, opioids, flight cancellations, the Russian/Ukraine war, space lasers, and the return of JFK Jr. — to name only a few.

Then the sun also rises on a new and equally terrifying day with another crisis added to the list or an old one resurrected.

If it’s not going to get any better any time soon, why not gamble on a bit of hope?

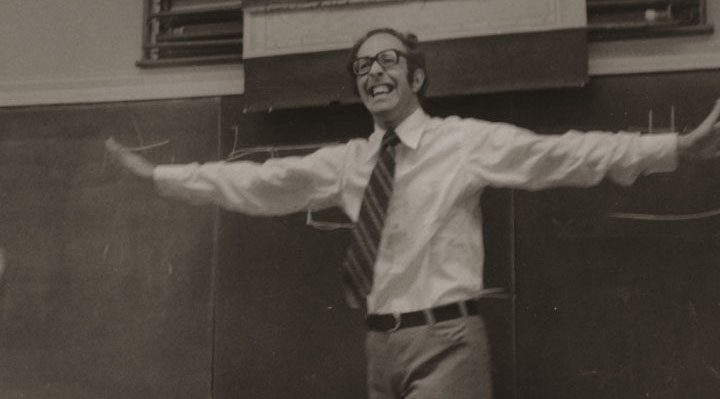

Bill Leonard

I recently remembered Hope in a Time of Abandonment, written in 1973 by French professor of history and sociology Jacques Ellul (1912-1994). Ellul wrote: “We live in a period of ‘abandonment,’ of God’s silence; and we also live in a day of hope, where (our) only reasonable response is to appeal to God to speak again.”

“If God seems silent to the world, here and now, then we surely have little to lose in seeking hope.”

While Ellul believed God continually encounters individuals, he sensed God’s absence from global human society because those cultures had turned elsewhere. Ellul wrote in 1973; what would he say in 2022? If God seems silent to the world, here and now, then we surely have little to lose in seeking hope.

I read Hope in a Time of Abandonment long ago, but I welcomed an insightful 2012 analysis from ethicist David W. Gill who wrote that for Ellul, “hope liberates. It relativizes this world and history because we know that absolute justice and peace can only occur with God’s gracious intervention at the end of history.”

Gill cited Ellul’s own observation that “freedom is the ethical expression of the person who hopes. Hope is the relation with God of the person liberated by God.”

Gill added that for Ellul, “Hope motivates our ethical behavior.” In Ellul’s words, it “brings with it … the relativizing of all things and a total seriousness applied to the relative.” Gill calls this “a future hope which guides our present, particular action. We are not called upon to purge, reform and manage the world as a whole. We are called to find ways of acting as faithful ‘signs’ of God’s promised future.”

Then, quite by chance, or grace, I ran across these words from the late priest/professor Henri Nouwen. I didn’t find hope; hope found me:

Those who help us most are not always those who give us new ideas,

but who radiate the presence of God — who in their person teach us.

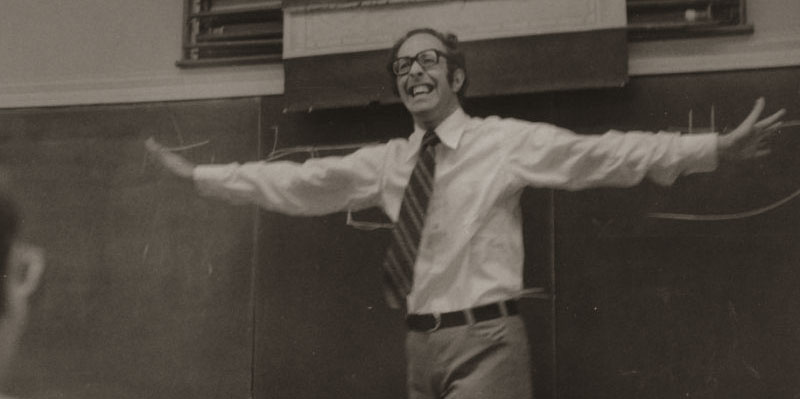

I wrote the words on an 8.5 x 11 sheet of yellow notebook paper on September 25, 1980, in a lecture hall at Yale Divinity School. It was the first day of Nouwen’s Introduction to Spirituality class, one of the most amazing courses I ever experienced. Our family was in New Haven as part of my first sabbatical leave from Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, where I was a newly tenured faculty member. Ensconced in divinity school housing, Candyce Leonard began classes in the Yale Spanish department, our daughter, Stephanie, age 5, started preschool at Celentano School for special needs children, and I signed up for a two-semester seminar with Sydney Ahlstrom, the renowned historian of American Christianity. Nouwen’s spirituality course was an unanticipated gift of grace.

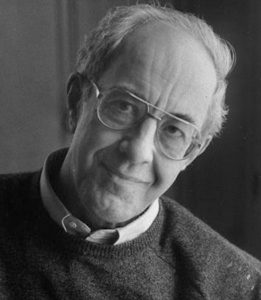

Henri Nouwen

Henri Nouwen (1932-1996), a Dutch Catholic priest, was in his final year at Yale, where he began teaching in 1971. He was a much-beloved professor and well-respected writer on faith, gospel and the spiritual life. The notes remain a treasure I’ve returned to across the years. Cleaning out my files on the way to eternity, I reread them, and that’s when hope showed up.

In 1980, Nouwen “radiated the presence of God” to our class. In 2022, notes from his class helped me recover hope in a time of abandonment.

Looking for hope, Nouwen taught me:

First, solitude is a source of spiritual hope. In that first lecture, Nouwen asked, “How can the life of the Spirit become a formative source of our faith? When we go to the desert.” In the internal solitude of the desert, “We get outside the compulsions of society and move from a compulsive lifestyle to a space in which the Spirit can speak to us and inform our entire being.” The desert, he said, has a “double meaning:” It is wilderness invoking struggle with the “demons” in society and inside us. It is paradise, a space where we encounter the hope-filled presence of the Spirit.

Cultivating life in and with the Spirit means moving from one way of being in the world, to another way of relating to the world. The issue is not “How can I be distinct?” but “How can I identify with the world in hiddenness and compassion?”

One place to start is with the quest for “solitude, silence and prayer.” He called solitude “the furnace of transformation,” a “private time” with God and with our “true selves.” Solitude restores us for action, a time of healing that enables us “to go back into the world.” It is “a quality of the heart, not something we do once in a while,” but a way we choose to live.

Second, hope is cultivated through silence. Silence is essential, Nouwen insisted, because the modern world “assaults us with words that keep us from listening” to God and one another. He said that in 1980 before cell phones, cable TV, email, Twitter, Facebook, four hours of Morning Joe, or an hour of Tucker Carlson.

“Silence is essential, Nouwen insisted, because the modern world ‘assaults us with words that keep us from listening’ to God and one another.”

Nouwen warned that continuous talking “avoids silence in which questions could be asked.”

He asked: “Where is the word that creates and recreates?” And answered: “The word as we hear it is born out of silence.”

Third, hope is a “new way of knowing.” On the last day of class, Dec. 2, 1980, Nouwen told us that Jesus is the source of a “new way” as taught in Scripture, meaning Scripture “is much more than infallible.” Inerrancy, he said, makes the text “static, dead, finished and understandable.” It “removes the mystery from Scripture,” turning it into a collection of “unquestionable doctrinal proof texts.”

The class ended 42 years ago. Father Nouwen died in 1996. In the solitude, the silence and the gospel, hope remains, unabandoned.

Bill Leonard is founding dean and the James and Marilyn Dunn professor of Baptist studies and church history emeritus at Wake Forest University School of Divinity in Winston-Salem, N.C. He is the author or editor of 25 books. A native Texan, he lives in Winston-Salem with his wife, Candyce, and their daughter, Stephanie.

Related articles:

Apocalypse now? If only it were that easy! | Opinion by Bill Leonard

It’s time to live like mystics | Opinion by Brett Younger