The tiny feet of a growing baby kicked my hand as we prayed with a young mother just south of the Texas border in Reynosa, Mexico. Surrounded by blankets on a concrete floor and the sounds of a refugee village encircling us, a local missionary named Alma Ruth had invited expectant mothers to join us for a prayer.

Within minutes there were 10 women huddled up together under the large canopy shielding us from the sun. Space and touch and words, translated into a moment of hope blowing through stagnant, repetitive days of waiting.

Colleen Burroughs

Every morning, thousands of asylum seekers along the southern U.S. border open the CBP-One phone app trying to schedule one of the 1,450 daily appointments. There is no time frame for this process, and some wait for days. Most wait for months. They wait in limbo, sheltering in whatever holding space they can find or afford for themselves and their families. This lottery-ticket waiting game represents the hope of a lifeline, but no guarantee of one.

Nevertheless, thousands of people keep coming. Many trek through the Darien Gap, a 66-mile strip of land that connects South America to Central America. This muddy, roadless jungle is the only land bridge north and is 100% controlled by a cartel.

Asylum seekers choose the uncertainty and danger of fleeing, weighed against inevitable life-threatening violence back home. They flee a precarious existence due to government instability, religious persecution, economic insecurity and war.

Once they pay their way through the gap and a dangerous trip through Mexico, those with any money left can wait for an appointment in an Airbnb or other rentable options. Those with little money wind up on the streets, in sketchy hostels or in one of a handful of refugee camps popping up on the outskirts of border towns.

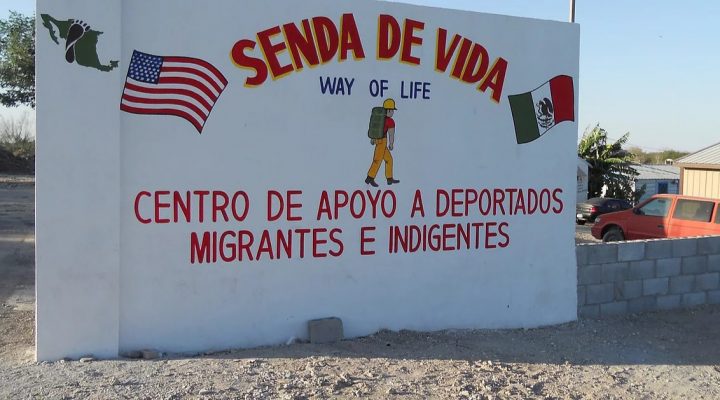

During a worship service at Senda La Vida, outside Reynosa, Texas, Ryon Price, senior pastor at Broadway Baptist Church in Fort Worth, Texas, is embraced by a new friend. (Photo by Cameron Vickery, Fellowship Southwest)

It was in one of these shelters, Senda La Vida, where we prayed with young mothers, danced with children and attended a Haitian church service.

Our small band of ministers was there at the invitation of Fellowship Southwest, an organization committed to loving neighbors with compassion and justice while crossing borders and pushing beyond boundaries. This was not a mission trip. We were there to witness in real time what immigration on both sides of the border looks like. We were there to grapple with a reality where thousands of people are stuck between the literal rock of their homeland and the actual hard place of a hoped-for promise land.

On the Texas side of the border, we worshiped at a church called Iglesia Bautista West Brownsville. This congregation is doing the impossible, unending work of welcoming strangers to the United States. Their building is minutes from the border and as of April 3, their hospitality ministry has welcomed 69,000 migrants and housed 2,459 individuals in their short-term respite center. We joined church volunteers passing out hotdogs and bottles of water to crowds of people who have gone through the process of securing an appointment, filling out paper work and crossing the border as asylum seekers.

We met a mother, her sister and three children who were staying in the church’s newly renovated respite house. The church renovated the pastor’s former house to make room for people who needed shelter. The family welcomed us with smiles and hugs and invited us in for handmade empanadas.

Having traveled from Venezuela, and being granted asylum, they were waiting for the next stage of their journey. One of the children, a 10-year-old boy, is in a wheelchair. As they told us about their journey through the Darien Gap we asked, “How did you get through the jungle with a child in a wheelchair?” They said, “People just helped each other.”

The Fellowship Southwest group

This newly arrived family daily chose matching T-shirts from the clothes closet and loaded up to help other church volunteers hand out hotdogs to the next crowd of immigrants, all with their paralyzed 10-year old in tow. The hotdog stand is just across the street from the border, and to each new face coming by they offer “Bienvenidos.” Welcome.

David Leonhardt, senior writer and columnist for The New York Times, says, “When experts try to explain why immigration rises and falls, they talk about ‘push’ and ‘pull’ factors.’ Immigrants move because something in a home country is pushing them out (war, corruption, violence, religious persecution). The prospect of entry level jobs, even while possessing post-graduate degrees, pulls immigrants away from the danger their families face for the hope of a better, safer life. The “push” for newly arriving Russian families at the border, for example, is Vladimir Putin’s call for young men to fight in the Ukrainian war.

“Of the 121 destinations to which Southwest Airlines flies, John was on his way to mine.”

Back at the shelter, I asked the expectant mother in my extremely basic Spanish, “Chica?” “Chico?” “Is it a boy or a girl?” She smiled at me and answered, “Dos.” Two babies! Los Gemelos! I explained I was the mother of twins as well. “Dios lo bendiga.” “God Bless you,” another friend helped me say.

A day later, on my Southwest flight back to Birmingham, I noticed a passenger clearly unsure about where to stand in line for his seat placement. “Hola!” I looked at his boarding pass and showed “John” where to stand near me.

The late Saturday flight to Houston was miraculously empty, and our flight attendants announced that everyone should spread out and relax. These words normally cause me to break into the Doxology and post a photo celebrating an empty row. As we boarded the plane, I motioned to John to put his bag in the overhead bin and then I slid into my open row and window seat. John closed the bin and then buckled up in the center seat right next to me. Perfect.

Of the 121 destinations to which Southwest Airlines flies, John was on his way to mine.

Our fore parents fled to America from religious persecution, famine and the hope of a better future for their families. And people are still fleeing. They are running away from their homes, and they are headed to your hometown. Churches need to take a cue from Iglesia Bautista West Brownsville, who today is blessing mothers, sharing hotdogs, welcoming strangers, making room.

Colleen Burroughs is co-founder and vice president of Passport Inc., a national nonprofit student ministry empowering students to encounter Christ, embrace community and extend grace to the world.