In an article published by the Liberty University student newspaper titled “Women Should Not Serve As Church Elders,” writer Jesse Hughes states plainly, “Women are able to assist the church in a wide variety of ways, but they should not serve in the role of pastor” and that both men and women are created equally, but God “assigned them to different roles” based on divine providence.

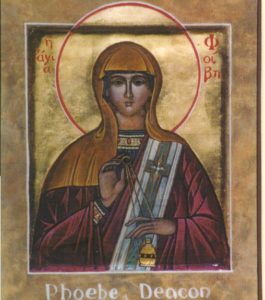

He uses Phoebe as an example, stating that she plays an important role in ministry but forgoes the authority of a title (despite being referred to by Paul as a “deacon” in Romans 16:1).

In contrast, other interpreters would view Romans 16 as a clear expression of women’s leadership in the early church. In fact, Paul greets four women in this passage — Phoebe, Prisca, Mary and Junia — one of whom is named before her husband (which was a big deal in ancient letter-writing), and another named alongside her husband as having been “prominent among the apostles.”

In contrast, other interpreters would view Romans 16 as a clear expression of women’s leadership in the early church. In fact, Paul greets four women in this passage — Phoebe, Prisca, Mary and Junia — one of whom is named before her husband (which was a big deal in ancient letter-writing), and another named alongside her husband as having been “prominent among the apostles.”

The book Band of Angels: The Forgotten World of Early Christian Women by Kate Cooper discusses how women have played an invaluable role in the growth and development of Christianity. Her book outlines a study on forgotten Christian women who, from all levels of society, helped to spread their faith. She discusses women like Lydia of Philippi mentioned in Acts 16, or Thecla, an early convert and disciple of Paul who was famous in early Christianity for her conversion narrative.

And although these women were powerhouses of faith in antiquity, the modern church has “airbrushed” them out of the conversation. In other words, we have allowed them to become background noise, and in some instances, we have forgotten about them altogether. We do not often talk about or teach about the importance of these women.

Our arguments about whether these ancient women really were leaders hinder us from seeing the spiritual gifts of women in both the ancient and modern church. Do we think God is unwilling, or perhaps unable, to call women into ministry?

This is a challenging question, especially considering the power and authority we assume of God.

What if, in early Israelite history, there were evidence that YHWH had a female consort? Even further, she is mentioned in the Bible, but just like women throughout Christian history, she may have been airbrushed from the narrative?

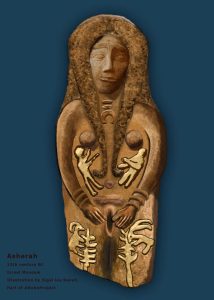

Canaanite goddess Asherah, 13th century BCE. From the Israel Museum via Wikimedia Commons.

The term “Asherah” occurs about 40 times in the Hebrew Bible, sometimes in reference to a deity named Asherah, and other times in reference to a cultic object. Here, the term “cultic” simply refers to the practice of worshiping something in an organized manner, such as worshippers using an altar to pray.

Hebrew Bible scholar Dan McClellan’s book YHWH’s Divine Images: A Cognitive Approach outlines what a deity is and explores multiple aspects of YHWH in the Hebrew Bible.

According to McClellan, the root words used to describe the Asherah in Hebrew suggest the cultic object in reference was made of wood. This suggests that she was “a special tree or wooden pole of some kind,” meaning that the phrase “the Asherah” can refer to an object used for worship.

In some texts, Asherah is referred to in English translations with the masculine singular pronominal suffix “his,” such as phrases like “YHWH and his Asherah” from the Kuntillet Arjud inscriptions. This phrasing, because of the use of a pronominal suffix, implies further that the Asherah was a cultic object.

Biblical scholar Nathan MacDonald furthers this by pointing out that it is “a bit odd” to refer to a person in this way. (He gives the comparison that one would not refer to a couple as “David and his Susan” because this is the incorrect use of the pronoun.) He thinks it is most likely the Asherah was some form of cultic object being worshipped during ancient Israelite history, but not necessarily a goddess.

However, he admits “we have a complicated picture of the Old Testament,” as there are certain parts of the Bible wherein Asherah seems to be “airbrushed” in and out. It is possible the cultic object named “the Asherah” was a representation of what worshippers believed to be a goddess.

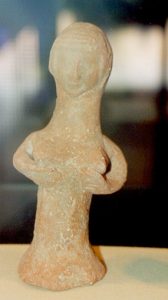

Pillar figurine of the goddess Asherah. Judea, 8-6th c. BCE. Eretz Israel Museum. Terracotta.

Another biblical scholar, Ellen White, also makes reference to this strange use of possessive pronouns. She says the term Asherah may refer to an object or could be the “proper name of the ancient Near Eastern goddess.” Further, she notes that in the ancient Near East, it was common for deities to be represented by physical objects used for worship.

White also discusses the presence of Asherah within the context of the Hebrew Bible, emphasizing an important theme in Deuteronomistic history (Joshua, Judges, Samuel and Kings): the rejection of gods that are not YHWH.

She thinks the ambiguous ways of referencing the worship of Asherah could be a means of demoting her from a goddess to “an object that could be discarded” in the biblical text, much like Hughes does when he nonchalantly argues that Phoebe’s authority should not be recognized, despite the text indicating she held a role of leadership.

Tilde and Hunter, in the book Asherah: Goddess in Ugarit, Israel and the Old Testament, solidify this claim when they state it is a “well-known fact” that cultic symbols like this would have been used by religious people to symbolize gods and goddesses, and it would be strange to consider an object being worshipped by people who did not believe it represented some sort of deity.

“Perhaps modern readers never will know the true story of Asherah. However, we can honor the women from church history who we do know about.”

They also note that when a goddess is connected to a god in the way in which Asherah is connected to YHWH in texts like the Kuntillet Arjud inscriptions, the goddess can be seen as the referenced god’s consort or wife.

So, who is Asherah: a goddess or an object? It seems the community of biblical scholarship is puzzled by her presence in the Hebrew Bible. If she was the ancient consort of YHWH, what does her ambiguous presence in the biblical text mean for believers today?

At some point in biblical history, YHWH must have shared, or perhaps competed for, power with the Asherah. Goddess or object, her presence in the Hebrew Bible indicates that at least some ancient believers thought Asherah could be powerful enough to warrant worship alongside YHWH, even if the Bible’s writers had mixed feelings about this.

However, with a name that has been “airbrushed” in and out of the biblical text and left out of church tradition and doctrine, perhaps modern readers never will know the true story of Asherah.

However, we can honor the women from church history who we do know about by learning about them and using their stories to inform our understanding of God’s calling on our lives. The knowledge of their contributions helps to empower modern women to understand and explore their spiritual gifts, rather than be airbrushed out of church leadership.

Mallory Challis is a senior at Wingate University and serves this semester as BNG’s Clemons Fellow.

Related articles:

Peter’s un-healing of Petronilla’s holy ‘palsy’ in the Coptic Act of Peter has a lesson for us today about disability | Opinion by Mallory Challis

I knew the truth about women in the Bible, and I stayed silent | Opinion by Beth Allison Barr

Fox News anchor gives voice to 16 women in the Bible

The invisibility of women in the Bible | Opinion by Grace Ji-Sun Kim