By Jeff Brumley

American churches already struggling with ways to attract young people got more bad news this week: Millennials don’t like them very much.

And worse yet, their esteem of religious organizations is dropping right along with that of the news media, the Pew Research Center offered in a study released Monday.

“Younger generations tend to have more positive views than their elders of a number of institutions that play a big part in American society,” the polling organization said. “But for some institutions — such as churches and the news media — Millennials’ opinions have become markedly more negative in the past five years.”

The numbers may be appalling to ministers and others tasked with convincing Americans born between the early 1980s and early 2000s.

Pew said that generation’s rating of religious groups fell 18 percentage points to 55 percent who say those organizations have a positive influence on the nation. It was about 73 percent five years ago.

“As a result, older generations are now more likely than Millennials — who are much less likely than their elders to be religious — to view religious organizations positively,” Pew said.

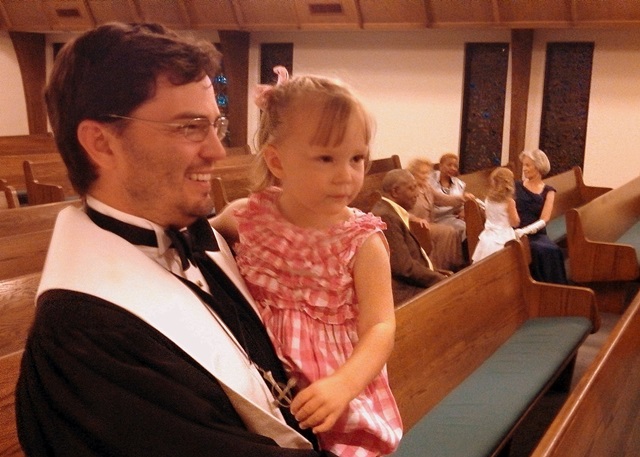

The research really came as no shock to minister — and Millennial — B. J. Hutto, associate pastor at Madison Avenue Baptist Church in New York City. And it shouldn’t surprise anyone else, either, given how advertisers and marketers targeted Millennials.

Until the late 1970s, housewives were the focus of advertising campaigns because women were seen as the agents of domestic spending.

“Then in the early ’80s they started to market to children … as the drivers of consumption,” he said.

That insight is based on a marketing article he read recently, but is also consistent with his own experience and his assessment of his contemporaries.

“Since we came home from the hospital [as newborns] my generation has been marketed to,” Hutto said.

That matters, he explained, because after a childhood where massive advertising efforts are tailored to your age group, it’s hard to believe any institution is genuine.

“What happens is you get pretty jaded and you get a pretty strong sense … when someone is trying to sell you something,” Hutto said.

By the time they are teens, Millennials were able to “sniff out pretty quickly” when somebody wanted something from them. They also developed a cynical attitude toward much of what was shoved their way by advertisers.

“Since we were kids we have been sold things that are plastic and disposable,” he said. “We were sold planned obsolescence.”

Being skeptical of products translates for many members of the generation into being skeptical about other things — including church.

For some, it may have started with the rise of the praise churches during the 1990s and early 2000s, Hutto said.

With music designed to look and sound like modern music, and other trappings, the movement came across in some cases as little more than an effort to lure people through the doors.

“People are starting to get turned off to it.”

Signs of that include college-age Catholic students demanding Latin Masses, he said. But Hutto also warned that statistics in the Pew and other reports be viewed cautiously. Many Millennials do not attend church because their opinions of religious groups may come from second-hand sources, such as media reports.

It could be that many young people base their opinions on the reporting of issues like the Catholic church sex scandal and more recent coverage of the same-sex marriage debate.

“When they say they don’t like or trust church, we need to be aware of what they are talking about,” Hutto said. “Especially with young people, what do they mean by ‘church?’”