The United Methodist Church’s premier edifice has stood for 100 years as a symbol of Christian social witness for peace and justice in the U.S. capital city. Now as they mark its centennial, trustees and tenants of the United Methodist Building in Washington, D.C., also prepare for a danger against which many national experts are warning: the threat of political violence like the January 6 insurrection that invaded the U.S. Capitol.

The General Board of Church and Society, which manages the United Methodist Building, plans a ceremony at 1 p.m. Feb. 13 to launch a year of celebration in Washington. The ceremony will be livestreamed on Church and Society’s YouTube Channel. The agency also is publishing an online history, “On This Day,” noting significant events in the building’s life.

As the centennial proceeds, however, national security experts have been warning repeatedly that government agencies should prepare for the possibility of political violence during the 2024 election year, judging from heated political rhetoric on the campaign trail and in social media posts. Because of its location in the Capitol Complex and its social witness purpose, the five-story wedge-shaped United Methodist building lies within a zone of vulnerability.

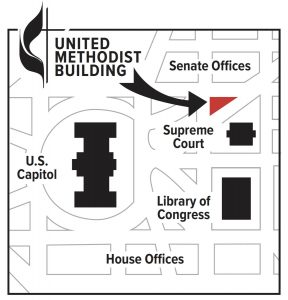

Situated at 100 Maryland Avenue NE, a quarter mile from the U.S. Capitol, the United Methodist Building forms part of the Capitol Complex. It’s the only non-governmental institution within the bounds of the legislative and judicial seats of U.S. government. United Methodist-related bodies located in the UMB, as it’s known, include the General Commission on Religion and Race, the General Council on Finance and Administration, and Church and Society. In total, 48 office and residential tenants occupy the UMB.

Situated at 100 Maryland Avenue NE, a quarter mile from the U.S. Capitol, the United Methodist Building forms part of the Capitol Complex. It’s the only non-governmental institution within the bounds of the legislative and judicial seats of U.S. government. United Methodist-related bodies located in the UMB, as it’s known, include the General Commission on Religion and Race, the General Council on Finance and Administration, and Church and Society. In total, 48 office and residential tenants occupy the UMB.

Security for the Capitol Complex has become a greater concern in the wake of the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection that attempted to block Congress’ certification of the 2020 presidential election. Frequent protests occur across the street from the UMB on Supreme Court Plaza as the high court takes up hot-button issues such as abortion and LGBTQ rights.

Jeffrey Corey, Church and Society communications director, responded to questions regarding security at the United Methodist Building. While understandably reticent on protection specifics, Corey confirmed the United Methodist Building has a strict security protocol in place while attempting to maintain Christian hospitality.

“The staff, tenants and property at United Methodist Building offices and attached residences are protected by multiple enforcement agencies coordinated to provide security and safety for the entire Capitol Hill Complex,” Corey said in an email. “Decades of agency security training, protocols and safety procedure have established a strong Capitol Hill security force minimizing risks and vulnerability.”

Tenants gain access to the building through coded key cards, while visitors must register in the lobby before entering offices or attending events, Corey said.

Although primarily served by the District of Columbia’s Metropolitan Police, the United Methodist Building’s security team cooperates with the Capitol Police and the Supreme Court Police Department, Corey said. He added that Capitol Police and Supreme Court Police sometimes can respond more quickly to an emergency at the UMB.

The United Methodist Building’s proximity to power began as an effort to rid the United States of social evils Methodists believed were caused directly by alcohol consumption.

The United Methodist Building’s proximity to power began as an effort to rid the United States of social evils Methodists believed were caused directly by alcohol consumption.

Funded mostly by small donations from laypeople, the United Methodist Building opened on Jan. 10, 1924. Originally owned by the Methodist Board of Temperance, Prohibition and Public Morals, it served as the headquarters of Methodist efforts to support Prohibition, the 1920-1933 era when federal law banned the production, import, transport and sale of alcoholic beverages.

When Prohibition ended, the Methodist Building’s purpose evolved as the site for the church’s efforts to “promote justice and pursue peace,” according to a history of the building, “For Justice and Enduring Peace: One Hundred Years of Social Witness,” written by Jessica M. Smith, Church and Society’s senior director of research, planning and spiritual formation. Social justice demonstrations often begin their marches with worship in the building’s Simpson Chapel, where in 1983 Coretta Scott King led the first observance of the federal holiday commemorating her late husband, Martin Luther King Jr. The UMB also has been a staging area for ecumenical clergy, such those that joined in the 1968 Poor People’s March for Jobs and Justice.

Even as the UMB guards against political violence, Church and Society works to preserve its tradition of hospitality to those seeking rescue from many social ills, according to the introduction of Smith’s UMB history. She cites social concerns such as racism, criminal justice, police brutality, migrant justice, immigration, non-violence, peace, public health, economic justice, creation care and environmental racism as topics that previous and current generations have given as important issues.

Church and Society directors underscored the building’s lasting significance in a video opening the centennial observance.

Church and Society directors underscored the building’s lasting significance in a video opening the centennial observance.

“There’s not many places in Washington where you have a holy place next to so many public government spaces,” said Raúl Alegría, a Church and Society director from the Nashville-based Tennessee-Western Kentucky Annual Conference.

Speaking in French, Bishop Daniel Lunge of the Democratic Republic of Congo said the United Methodist Building has an impact in his African country as well.

“Few Congolese have visited the building,” he said. “Yet my people have an idea of the symbolism of peace, but also of justice that the building represents.”

Video narrator Bailey Varness said, “Today, the United Methodist Building continues to be a gathering place for the faithful to be energized for the sharing of ideas and beliefs and to pursue a common purpose.”