I should have figured this out right away, but it took me several months of driving by the mid-sized Baptist church building on the busy freeway to connect all the dots. The church I knew had been battling decline for years suddenly was getting an exterior facelift. New paint, new HVAC, new landscaping, new roof, new construction.

These are not things dying congregations spend money on.

Then I found the answer online. Park Central Baptist Church was merging with Lakepointe Church, a multi-campus Baptist church based in the Dallas suburb of Rockwall. The new North Dallas campus will be Lakepointe’s seventh metro Dallas location. It also will be the third of those locations to occupy the property of a dying Baptist congregation.

Then I found the answer online. Park Central Baptist Church was merging with Lakepointe Church, a multi-campus Baptist church based in the Dallas suburb of Rockwall. The new North Dallas campus will be Lakepointe’s seventh metro Dallas location. It also will be the third of those locations to occupy the property of a dying Baptist congregation.

Lakepointe is far from alone in this pattern. Mergers and acquisitions of church properties is big business nationwide these days, as multi-campus megachurches take over the buildings of dying congregations.

“Mergers and acquisitions of church properties is big business nationwide these days, as multi-campus megachurches take over the buildings of dying congregations.”

Three models

There are at least three ways this happens. In the most straightforward option, a church plant or growing young congregation purchases the property of a congregation in decline. These can be multi-million-dollar deals.

A second option, which is a variation on the first, is that a church closes and deeds their property to the local Baptist association, which then sells the property to another congregation in need of space. (Similar things happen in connectional denominational bodies too.) I’ve been in the middle of one of these deals before and, frankly, it made me angry that the association profited off the property that was gifted to it and pocketed quite a bit of money from an ethnic congregation.

The third option is the most interesting, though. This is when a dwindling congregation with a large facility that has been neglected due to lack of funds and volunteer manpower essentially hands over the keys to a larger congregation to create a satellite church. While this might appear to be a windfall for the acquiring congregation, consider the investment required to bring such a church property up to contemporary standards.

The third option is the most interesting, though. This is when a dwindling congregation with a large facility that has been neglected due to lack of funds and volunteer manpower essentially hands over the keys to a larger congregation to create a satellite church. While this might appear to be a windfall for the acquiring congregation, consider the investment required to bring such a church property up to contemporary standards.

In the case of the Park Central and Lakepointe merger happening near where I live, the church building has been closed for six months while major renovations are taking place. Lakepointe obviously is investing millions of dollars to bring the facility up to its standards and to make it inviting to the ever-sought after young families of church growth fame.

“Megachurches with resources and resolve can swoop in and grow a thriving congregation where the previous occupants no longer could make a go of it.”

We’ve seen this play before, and the odd thing is, it works. Megachurches with resources and resolve can swoop in and grow a thriving congregation where the previous occupants no longer could make a go of it. In a short drive across North Dallas, I could show you multiple places where this very thing has worked.

More attend larger churches

What’s ironic about the new Lakepoint North Dallas campus is that it’s located almost directly across a major freeway from one of the largest nondenominational Bible churches in town. You could stand in the parking lot of either church and see the other across 12 lanes of highway.

To the older dying church, this was a liability. To the incoming satellite campus, location trumps competition.

All this fits the pattern church researchers have been telling us about: America is increasingly a place where even though most churches are small, most people who attend church go to a large church. More than half of American churchgoers attend just 9% of the churches in America.

The sifting currently happening in American congregational life shows up most visibly in real estate. This is illustrated by a series of concurrent events happening in the section of North Dallas where I live — again, mirroring national trends.

Dallas as a case study

Apart from the Lakepointe acquisition already mentioned, I am aware of at least four church property deals happening at the same time within a 15-minute drive from my house.

Eastside Church now merged with Scofield Bible Church in the facility that used to be Scofield.

First, the historic Scofield Memorial Bible Church (yes, named for C.I. Scofield of Bible commentary fame) recently merged with a church plant called Eastside Community Church. Scofield is a nondenominational church that dates to 1877, making it one of the oldest churches in Dallas County. Eastside is a nondenominational-appearing church with Baptist roots that launched in 2018.

Before the merger, Scofield Church had been in decline for a number of typical reasons, including a series of ill-fated decisions and a churn of pastors. Then Eastside Church began renting space in the building on Sunday afternoons. Before long, the tenant church had outgrown the landlord church, and a merger was proposed.

“Before long, the tenant church had outgrown the landlord church, and a merger was proposed.”

Now the signage on the building has been changed to say Eastside Church, and inside the building, the remnant of Scofield Church has blended into the church plant and they all meet together on Sunday mornings. The new church on its website has retained the history of Scofield Church and blended it into the brief history of Eastside Church.

A second-generation acquisition

But wait, because there’s even more to this story. This is a second-generation church merger or acquisition, depending on how you see it. Bear with me on this because I promise the payoff of the story is worth it.

Back in the early 1950s as Dallas was growing northward, a new congregation was started called Northway Baptist Church. This congregation grew and thrived in a time of easy church growth. As Dallas continued to expand, Northway sponsored a mission that would come to be known as Prestonwood Baptist Church. Of course, Prestonwood today is one of the largest churches in America.

Northway’s pastor at the time was Billy Webber, who originally preached at both Northway and at the Prestonwood mission every Sunday. Eventually, as Prestonwood grew, he had to make a choice between the two, so he resigned at Northway and became solely the pastor of the rapidly growing Prestonwood.

Northway rocked along, calling another pastor who was beloved and who served the church well. After a good while, though, he was called to another position and Northway began an all-too-predictable series of bad decisions, including hiring a pastor who unilaterally flipped Sunday worship from traditional to contemporary on about a week’s notice.

Soon the church split, and over the coming years, Northway was unable to rebound. They found themselves with a big building but only a few people. That’s when another Baptist church swooped in and acquired the property as a satellite campus in 2009.

“That’s when another Baptist church swooped in and acquired the property as a satellite campus in 2009.”

Northway Church before the tornado

The remnant of Northway Baptist Church became a senior adult Sunday school class at the new North Dallas campus of Village Church. You may know of Village Church, based in the far northern suburbs of Dallas, because of its well-known pastor, Matt Chandler.

Once again, where an existing Baptist church was declining and could not recover, a megachurch came in and turned things around. The once-dying church became a thriving outpost.

After the tornado

An interesting postscript to this story: By 2015, Village Church announced it would set its satellite campuses free to be their own congregations. That led to the Northway campus of Village Church becoming autonomous in 2019 and reclaiming two-thirds of its original name: Northway Church. One month later, a devastating tornado blew through North Dallas and demolished the original building but the congregation has survived.

Why have I told you this long story about Northway and Village Church? Because Eastside Community Church was started by the Northway campus of Village Church, making it a second-generation church merger — or acquisition, depending on your viewpoint. The very play that created the sponsoring church now has sustained its church plant.

Churches of Christ in flux

But that’s not the only notable church property deal going on in my neighborhood right now. There’s a notable church property swap happening just 6 miles down LBJ Freeway from the former Park Central Baptist Church location. And this one comes with a bit of a twist of historical irony.

Highland Oaks Church of Christ property being sold to Shoreline City Church.

Highland Oaks Church of Christ once was one of the largest congregations in the Dallas-Fort Worth area affiliated with the Churches of Christ. For a variety of reasons, its membership and attendance have declined — but not to the point of inevitable death. From a high of about 2,000 members, the congregation today reports about 400 members but insiders tell me average Sunday attendance is less than half that, which is a typical Protestant church ratio.

Highland Oaks occupies a 43,000-square-foot, two-story building situated on 18 acres — way more space than the church needs or can keep up today. On top of that, the church carries nearly $2 million of debt.

As church elders earlier this year debated what to do, they were approached by another congregation that has the opposite problem — too many people in too small a space. And here’s the irony: That fast-growing church, called Shoreline City Church, currently occupies the building Highland Oaks Church of Christ used to own.

“And here’s the irony: That fast-growing church, called Shoreline City Church, currently occupies the building Highland Oaks Church of Christ used to own.”

Previously known as Garland Road Church of Christ, the congregation built its earlier building in 1955 and stayed there until relocating to a new, larger building in 1983. With the move, the church changed its name to Highland Oaks.

After that move, various other churches occupied the original property, until Shoreline City Church acquired it in 2016.

Current location of Shoreline City Church

Now, Shoreline City Church is following Highland Oaks Church of Christ once more, having recently purchased their property for an undisclosed amount. A spokesman for Highland Oaks told the Christian Chronicle the sale will allow Highland Oaks to retire its debt and still have “sufficient funds to relocate in the same community but have millions of dollars in addition to invest in ministry and mission.”

This multi-million-dollar sale is made possible, in part, because a developer has bought the current Shoreline property and plans to create a mixed-use development with traditional multi-family rental units, two-story rental homes, creative office space and green space. Where the church currently stands, 310 housing units will be built.

By the way, Shoreline City Church also is a multi-campus church, but in this case the primary church location is what’s being upgraded.

Not dead yet

What’s notable about this church property swap is that Highland Oaks Church of Christ is not dead yet. It is a viable congregation, although much smaller than its former self. But with the infusion of cash from the sale of the property, many new ministries become possible.

Yet that, too, prompts soul-searching, as Highland Oaks already is perceived as a more progressive outlier amid the traditionally conservative Churches of Christ. Some internal critics claim the decline in membership and attendance over the last decade is “God’s judgment” on the church for its ministries addressing race and sexuality, for example. Changing locations won’t change that debate. It’s possible there will just be more money to fight over.

“Changing locations won’t change that debate. It’s possible there will just be more money to fight over.”

Another Churches of Christ congregation in North Dallas currently faces similar declines, and not because of progressive theology. Elders of Skillman Church of Christ had proposed a merger with a multi-campus nondenominational church called The Hills, based 30 miles away in Fort Worth.

Skillman Churcb of Christ

But when the formal proposal recently was put to a vote at Skillman Church of Christ, it fell two votes short of the two-thirds majority required for passage. Now church elders are rethinking and trying to pick up the pieces of the failed deal. An already fractured congregation now has 65% of its people who wanted the merger and are disappointed it failed by such a slim margin.

A longtime member of the church told the local Advocate magazine that the declining church will now attempt to try harder in its current location — even though that hasn’t worked for a decade or more. “We need a period of healing,” said Don Williams, a 50-year member of the church who opposed the merger. “Once that is over, I believe we can reboot Skillman Church of Christ 2.0 with a message of service to the members, community and the poor.”

History shows that is a strategy doomed for failure. Whether or not the merger with The Hills was the right option or not, its rejection not only has thrown the church backward but has added to the dissent and dysfunction.

Thus, two Churches of Christ congregations in the same city now face very different futures because of decisions about their properties.

Not a new phenomenon

The sale and swapping of church properties is not a new phenomenon. What’s different today is the ability of multi-site megachurches to make an almost instant success of locations where other churches have declined.

Park Cities Presbyterian Church

I was reminded of the deep history of church property swaps the other night as we ate dinner in a restaurant on the edge of the posh Park Cities/Turtle Creek neighborhood just north of downtown Dallas. Looking out the window, I saw next door the majestic and historic building of Park Cities Presbyterian Church. Except for most of its history, that building was not a Presbyterian Church but a Baptist church.

Park Cities Presbyterian Church was created in 1991 out of the split with Highland Park Presbyterian Church. The original church at the time was affiliated with the mainline Presbyterian Church (USA). The new church affiliated instead with the more conservative Presbyterian Church in America.

The new congregation attracted 1,500 people on its first Sunday, meaning a large facility would be needed pronto. The Presbyterians quickly worked out a deal with Highland Baptist Church, a once-grand congregation that by then was rattling around in an enormous sanctuary far too big for its needs. The Baptists welcomed the Presbyterians as tenants. Two years later, the Presbyterians purchased the historic property outright, and the Baptist remnant moved to another location (more on that in a moment).

Let’s return for a moment, though, to the impetus that created a new Presbyterian church in central Dallas. It resulted from a failed attempt to get Highland Park Presbyterian Church to leave the PCUSA because of its perceived liberalism in regard to social issues, sexuality, biblical interpretation, female clergy and more. In 1991, this mirrored the schism raging within the Southern Baptist Convention.

In a story that would be well understood by the folks at Skillman Church of Christ, the motion to leave the PCUSA was affirmed by a simple majority but not by the required two-thirds majority. The vote was 2,001 to remain in the PCUSA and 2,563 to leave.

“At that time, Highland Park Presbyterian Church, with 7,000 members, was the largest and perhaps wealthiest PCUSA church in the nation.”

Highland Park Presbyerian Church

At that time, Highland Park Presbyterian Church, with 7,000 members, was the largest and perhaps wealthiest PCUSA church in the nation. Ironically, later the congregation would indeed vote to leave the PCUSA and affiliate with a new body called ECO: A Covenant Order of Evangelical Presbyterians. This split was motivated largely by the same issues as before, but especially LGBTQ inclusion.

I’ve been inside the sanctuary of Park Cities Presbyterian Church several times. It is a grand and glorious and cavernous space. Which set me to wondering on more than one occasion: How did a Baptist church that once was large enough to build such an edifice reach the point of moving away to a property one-tenth of the size?

That took some research, but the answers are fascinating. And they illustrate how the very problems of church decline we think are “new” today aren’t new at all.

Enter J. Frank Norris

What eventually became known as Highland Baptist Church began in 1905 with a young new pastor who later would become infamous across the Trinity River in Fort Worth: J. Frank Norris.

“Fresh out of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, the young Norris was called to Dallas to launch a new Baptist church.”

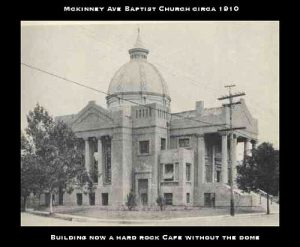

Fresh out of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary, the young Norris was called to Dallas to launch a new Baptist church in an area of Dallas that is so close to downtown that today it’s called Uptown but then would have been the far reaches. According to a Dallas Landmark Commission report, at the time McKinney Avenue Baptist Church erected its first building in 1906, there were “nine white Baptist churches in the city.”

The McKinney Avenue church grew rapidly and continued its growth even after Norris resigned in 1908 to become editor of the Baptist Standard newspaper.

The McKinney Avenue church grew rapidly and continued its growth even after Norris resigned in 1908 to become editor of the Baptist Standard newspaper.

By 1922, the church burned its mortgage, reportedly becoming the first Baptist church in Dallas to be debt free. Just three years later, in 1925, the McKinney Avenue congregation said it would move a short distance away and erect a new building, following a trend the Dallas Morning News reported as record attendance at Dallas churches.

The Great Depression interrupted those plans, however, and the grand new building was not completed until 1937. With the move, the church changed its name to Highland Baptist.

By the way, that original building that housed McKinney Avenue Church eventually became a Hard Rock Café but now has been demolished.

The congregation begun by J. Frank Norris remained in its new spectacular building with a 2,000-seat sanctuary for another 30 years but in time could not sustain itself. Why that happened is a story I’ve not been able to dig out, despite quite a bit of research. Best I can tell, it’s a classic tale of not adapting to change and of a series of unfortunate leadership decisions.

A three-way property swap

However, what happened next is a three-church property swap that was so unusual it made local news.

Highland Baptist sold its enormous building to Park Cities Presbyterian and in turn bought a much smaller church property owned by Fellowship Bible Church several miles north. In the same deal, Fellowship Bible Church bought a nearby office building and converted it to a church property.

Highland Baptist moved from a high-profile location on a major thoroughfare to a much-smaller location tucked in a neighborhood so tightly that you’d have to know it was there to find it. Honestly, I drove by the back side of that church for years before I realized there was a church there.

And to add one final ironic twist to this story, most recently the remnant of Highland Baptist Church has become a cowboy church — still in the same building which happens to be located within walking distance of NorthPark Center, one of the most affluent and successful shopping malls in America. Dallas, y’all.

And to add one final ironic twist to this story, most recently the remnant of Highland Baptist Church has become a cowboy church — still in the same building which happens to be located within walking distance of NorthPark Center, one of the most affluent and successful shopping malls in America. Dallas, y’all.

This is American religion today

The stories I’ve just told are not unique to Dallas. I’ve merely used my neighborhood as an example of what’s taking place — and has taken place in the past — all across America. Go to any major city in the nation and you’ll find similar stories; the denominations and church names may be different, but the stories sound eerily alike.

“I’ve merely used my neighborhood as an example of what’s taking place — and has taken place in the past — all across America.”

While there are no published statistics on church property swaps and sales and mergers and acquisitions today, it’s clear we’re experiencing a new wave of all the above. And it’s also clear that the secret ingredient making it work is the multi-site church. That’s not the only explanation, but it is a big part of the story.

The other lesson is that while location matters, it does not breathe life or death into a congregation. Church plants and multi-site churches are doing great in the very locations where other churches couldn’t make a go of it.

The old real estate slogan about “location, location, location” does not always apply to churches. And it’s important to acknowledge that whatever the location, churches — like neighborhoods — have natural life cycles.

Just because you can fill a 2,000-seat sanctuary today doesn’t mean you will be able to do the same in 10 years. To everything there is a season.

Related articles:

7 dos and don’ts when considering the redevelopment of church property | Opinion by Rick Reinhard

Let’s reimagine how your church property might serve the community | Analyis by Brian Foreman and Justin Nelson