Government, industry and nonprofit groups must be dedicated to working together to accomplish President Joe Biden’s vision of eradicating hunger by 2030, said Jeremy Everett, executive director of the Baylor Collaborative on Hunger and Poverty.

“No one sector can end hunger by itself. It requires collaboration, which has been articulated by the president himself,” Everett said in an interview this week.

And that cooperation must include buy-in and leadership from religious organizations and communities, he added. “Every religious tradition has a component about addressing hunger as a core tenet of faith. It’s imperative of us, as people of faith, to lead the way.”

Jeremy Everett

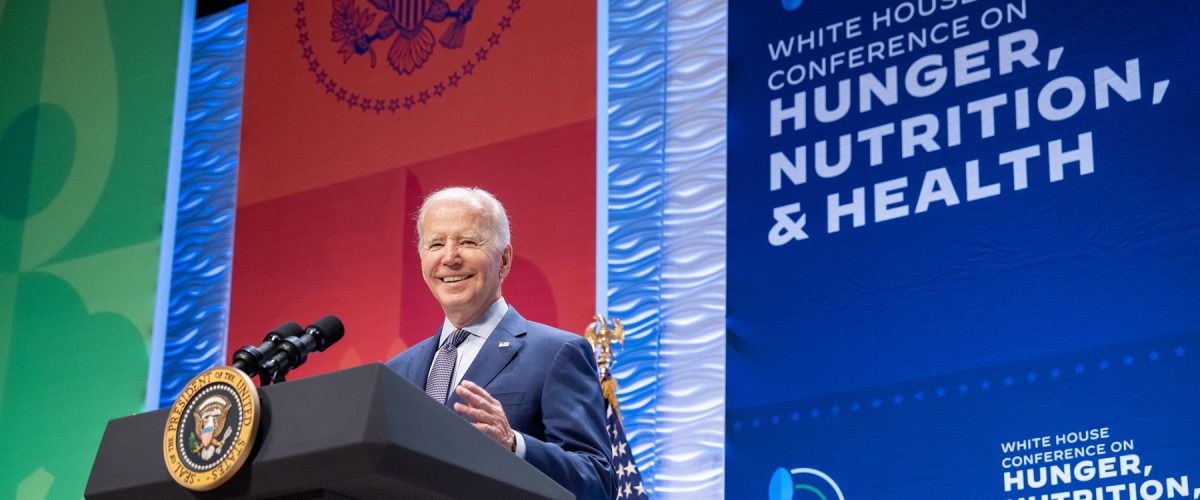

Everett joined others at the forefront of combating food insecurity in the U.S. in attending a Sept. 28 White House conference focused on ending hunger in the next eight years. This was the first such summit since President Richard Nixon convened one 53 years ago.

The gathering in Washington, D.C., featured private- and public-sector leaders called together to hear and discuss the president’s vision for ending hunger and to suggest ways their organizations could participate.

“It was an important opportunity to have a lot of conversations with people from across all sectors, and with individuals experiencing food insecurity. There were grassroots organizations and Fortune 500 companies that are working on this,” Everett said. “It was important for us, as the nation’s largest university-based hunger research innovation project, to have a seat at the table to hear what they are thinking.”

“It was important for us, as the nation’s largest university-based hunger research innovation project, to have a seat at the table to hear what they are thinking.”

The White House plan was pitched as five “pillars” of action: improving the accessibility and affordability of healthy food; integrating food security with overall health; helping consumers make healthier food choices; promoting exercise and other physical activity; and expanding nutrition and food insecurity research.

Biden’s effort already has generated $8 billion in philanthropic and in-kind contributions, of which $2.5 billion is earmarked for investment in start-up companies developing innovative solutions to hunger, and more than $4 billion is devoted to improving nutritious food access, healthy eating choices and exercise, the White House said.

The president’s initiative also sought ideas and commitments from companies and nonprofits involved in combating food insecurity. Responses included AARP’s pledge to conduct research into the use of the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program by senior adults, and a commitment by DoorDash to work with its partners to provide food delivery from food pantries.

“Each of these commitments demonstrates the tremendous impact that is possible when all sectors of society come together in service of a common goal,” the White House said.

Second Gentleman Doug Emhoff, Avani Rai, Joshua Williams and Director of the Domestic Policy Council of the United States Susan Rice spoke during the White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health.

The Baylor Hunger Collaborative submitted a proposal presenting three strategies to meet the pillars presented at the conference.

The first is to maximize participation in child nutrition programs during summer months. Tailored to the needs of individual communities, this strategy would ensure access to healthy meals when school is not in session.

“Culturally appropriate and context-specific options — including congregate meal sites, Summer EBT, and non-congregate alternatives, like grab-and-go or Meals-to-You — expand food access and increase participation in child nutrition programs,” the proposal explains.

Meals-to-You, or MTY, is an ongoing collaboration between Baylor and the U.S. Department of Agriculture to deliver nutritious summertime meals and snacks to children in rural and remote areas. With schools closed in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the program delivered 40 million meals to children in 43 states and Puerto Rico.

“Today, the program represents a proven model for ensuring seamless access to safe, reliable food. BCHP urges Congress to extend and expand MTY as an option for summer nutrition programs,” the proposal explains.

The document also pitches the development and strengthening of public-private partnerships to fight hunger.

“No one sector can end hunger alone. By building robust collaboration between government, business, nonprofit, and faith-based entities, we can together create solutions for a more equitable, food secure future,” the proposal says. “Public-private partnerships strengthen capacity to foster environments where healthy food is the easy economic choice for all.”

But realization of these strategies, and of the president’s vision as a whole, requires them to be included in mandatory spending plans, Baylor leaders said in the proposal. “Currently, funding streams, eligibility and delivery systems, and accountability mechanisms operate separately, resulting in fragmented rules and regulations confusing to administrators and community members alike.”

The Baylor collaborative also urged funding of research into populations most affected by food insecurity: “Systemically under-resourced communities — including Black, indigenous, Latino, underserved rural, migrant, disabled, and those impacted by incarceration — experience disproportionate barriers to food and nutrition security. Yet, there is limited research exploring factors that shape disparities and solutions to improve food and nutrition equity.”

Everett said the president’s goal of eliminating hunger by 2030 is reachable. “Right now, we are at just over a 10% food insecurity rate, which is about as low as it has ever been in modern American history.”

“We are making major strides as a country toward equity, and that’s where we want to be.”

And while that rate likely will increase due to inflation, a united effort by government and private sectors could conceivably knock it down to 5% or 6% in the foreseeable future, he said. “If we’re moving in that direction, then we are making major strides as a country toward equity, and that’s where we want to be.”

However, it’s too early to tell if the collaboration requested by the president will materialize, Everett said. “With conferences like that, you won’t know for weeks and months how effective that moment was. Right now, we know we have a vision we can all agree upon and say this is where want to go. What we don’t know is, are we going to get there?”

Regardless, experience in Texas shows the fight against hunger must include people of faith, he added. “Baptists in Texas have been leading the way in addressing hunger for 70 years, and I think this is a time for Baptists to step up. The only way we end hunger in Texas is if everybody does their part. No days off. Engage here and there. This is something that 5,500 churches in Texas have the capacity to do, and they are leaders in their communities.”

Now, that message translates to the national level, Everett said. “I would definitely say people of faith need to step up. Our salvation is intertwined with loving our neighbor as ourselves, and we know as people of the Christian faith that we are a called to feed the hungry.”

Related articles:

New endowed academic chair will lead Baylor in research to end hunger

Baylor initiative feeds 270,483 children in 43 states amid a global pandemic

Baylor preparing to launch master’s degree in theology, ecology and food justice