As universities nationwide seek to diversify their student bodies — sometimes against the backdrop of political mandates not to talk about diversity and equity — one Baptist school in the Deep South continues to succeed year after year.

Fall enrollment at Mercer University in Macon, Ga., was 9,164 across all campuses, and half those students are people of color, according to Penny Elkins, senior vice president for enrollment management.

Penny Elkins

“When I can look at a prospective student event like I did a few Saturdays ago and I’m looking across the room, I get tears in my eyes,” she said. “I’m very emotional about this. I look across that audience and I see a beautiful sea of Hispanic, Asian, African American, Caucasian prospective students. I’m thankful we get to do this, because it’s the way education should be.”

Not only is the Mercer student body diverse, it is growing, Elkins said. “We are celebrating record enrollment for the university once again, and I say that in all humility because I know it’s really difficult, actually, to attain that record enrollment. We have done so every year for the past 16 years, except one.”

Those students study in 12 colleges and schools across seven locations in the state of Georgia. This year’s record enrollment also included a record number of incoming freshmen, 1,015.

Mercer stands out compared to many private universities across the country that face declining enrollment and far-less-diverse student bodies. Most of Mercer’s students (87%) come from Georgia, where the general population is 55.85% white, 31.54% Black, 4.85% mixed race and 4.22% Asian. Bibb County, where Mercer’s main campus is located, is 57% Black.

Mercer is one of dozens of liberal arts colleges founded in the 19th and early 20th centuries by white Baptists affiliated with the Southern Baptist Convention and various state Baptist conventions. Mercer broke ties with the SBC and the Georgia Baptist Convention years ago.

Diversity is part of Mercer’s DNA, Elkins said. “Changing the world, that’s our mission, and so many aspects of that mission are to impact areas of need in our state.”

Mercer was “the first institution in the state of Georgia to voluntarily integrate,” she noted.

In 1963, Sam Jerry Oni of Ghana became the first Black student to enroll at Mercer. On April 18 that year, Mercer trustees voted to admit qualified students without regard to race. Mercer became one of the few private colleges in the South to do this before being required to do so by the 1964 Civil Rights Act.

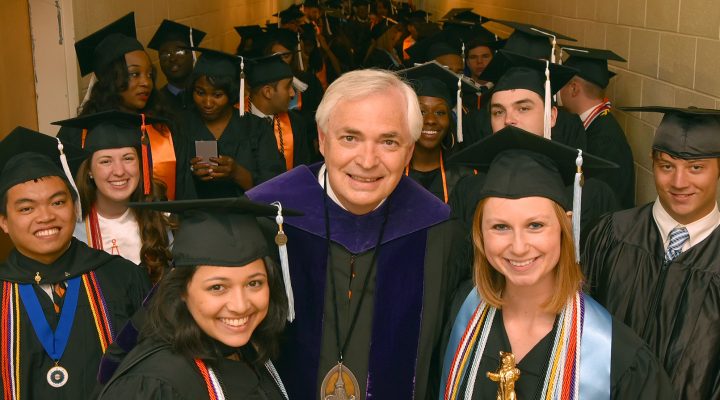

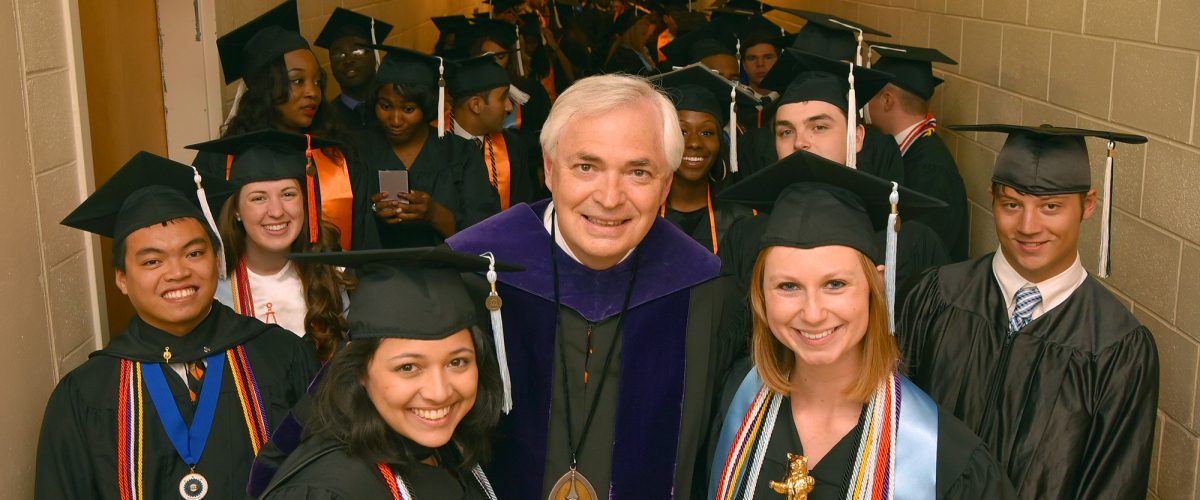

Mercer students at commencement (Mercer photo)

Elkins sees her work in admissions as an extension of an important legacy. Asked the reason for the continued success in enrollment growth and diversity of student body, she had a ready answer: “No. 1, leadership matters. There’s nothing like it. Leading this university with Bill Underwood has been amazing. He’s an amazing leader.”

Underwood has led the university since 2006 and has presided over a 25% growth in enrollment in that time.

Among numerous high-profile foundation gifts and honors, Mercer has been asked by the Lettie Pete Whitehead Foundation to speak on the university’s success in diversity.

“We’re actually going to do a presentation together, for the Lettie Pete Whitehead Foundation in January,” Elkins explained. “So, we’ve been thinking through how we ended up here. Honestly, it’s not because of (Underwood’s) amazing leadership. And it is amazing. It’s not because of anything I have done within the admissions; we already had a foundation laid. We’re carrying that foundation on in reaching a diverse body of students.”

She particularly cites the leadership of the university’s 16th president, Rufus Harris, who led Mercer from 1960 to 1988. Not only did he co-author the G.I. Bill to provide benefits for veterans returning from World War II, he led Mercer toward integration.

Harris “was on the cutting edge of all things in terms of diversity in laying that foundation for our legacy,” Elkins said. “There are all kinds of stories out there about how we stood firm on issues of race and diversity.”

And it wasn’t just Harris who paved the way, she continued. Another notable example is “Papa” Joe Hendricks, a beloved professor and administrator from 1959 to 2000.

Biology lab at Mercer University (Photo by Christopher Ian Smith)

A profile of Hendicks on Mercer’s website explains: “He helped bring the first Black student, Sam Oni, to campus in 1963 and worked relentlessly to make diversity an asset to the university community. Generations of alumni have recalled with fondness how Dr. Hendricks made an effort to get to know them personally, checked on them frequently and was always there to help. He believed that Mercer was not just a school but a family.”

Elkins says the university continues to benefit from Hendricks’ influence, including his commitment to reach out beyond the campus.

“He would go around to the neighborhoods and tutor African American children because he wanted them at Mercer,” she said. “He would say, ‘If we want them to be at Mercer, then we have to help prepare them to be at Mercer.’ Because of his leadership, Mercer University started a program that then evolved into the federally funded Upward Bound program that we know of today. “

Former Mercer President Kirby Godsey said Hendricks was “a singularly compelling figure in the history of Mercer University. For a generation of students, he was not only their most influential teacher but also became their moral compass. He taught with passion and he embraced students with a listening ear and genuine respect. He taught all of us that coming to the university was not only a journey of learning, but also a journey of wrestling with the values that should shape our lives.”

When Elkins looks out over Mercer’s student body today, she sees the fruit of those seeds planted long ago and is proud to be part of the story.

Related articles:

Mercer University dedicates new $50 million Medical School campus

The pandemic slowed down Mercer on Mission but a $10 million gift is powering the future

What to do if you unearth a history of slavery in your church, college or institution?