Sex offender registry guidelines should be updated to more accurately reflect those ex-convicts who remain true threats to others, according to the Missouri Alliance for Family Restoration.

MOAFR claims the current registration requirements do not align with the actual level of threat many people previously incarcerated for sex crimes pose for society, and were formulated using outdated and inaccurate statistics. Members of the organization argue the registration requirements should be less strict than they currently are, as to offer “a fair chance to live a productive life to those who have paid their debt to society.”

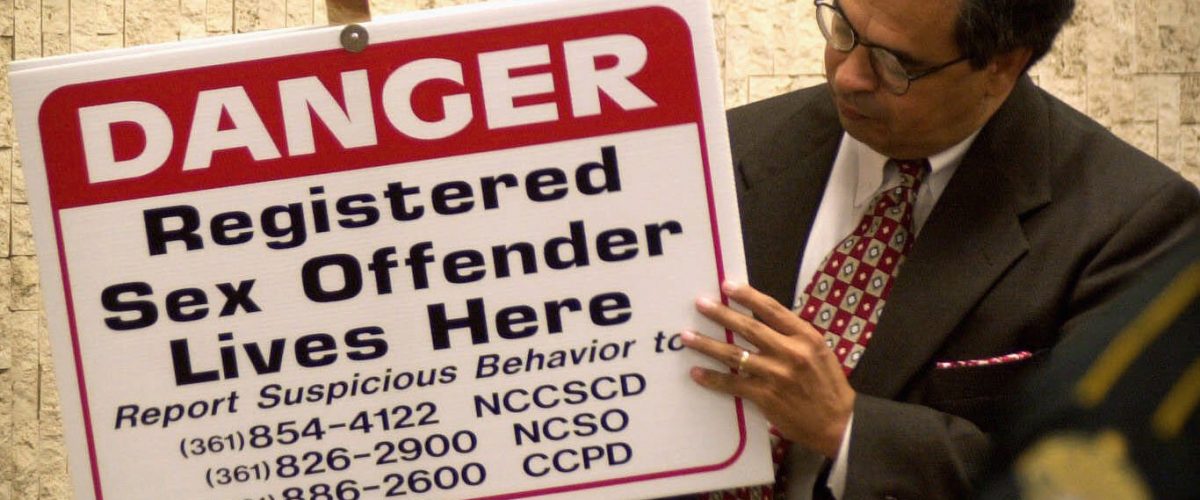

Advocates claim the rigorous, publicly shaming registration lists — which typically publish the names, photos, addresses and workplaces of sex offenders — hinder the ability of rehabilitated offenders to successfully integrate back into public society even if they no longer pose a reasonable threat to those around them. Due to the restrictions placed upon registrants, many face difficulties finding housing, seeking educational opportunities, applying for or accessing jobs, reuniting with their families and sometimes being banned from drug rehabilitation or treatment centers.

More recent research shows the rate of recidivism for low- to moderate risk offenders is somewhere between 2% and 7%.

And due to the public nature of the sex offender registry, registrants face various kinds of private or public discrimination, such as being harassed, both verbally and violently, at their homes or workplaces. Last March, for example, a sex offender in Grand Marais, Mo., was bludgeoned to death in his home with a shovel and a moose antler by the father of a child he had allegedly stalked while parked in his van outside of a day care.

In advocacy of reformed legislation on sex offender registry requirements, MOAFR cites stories like this, claiming the broad requirement that all sex offenders, regardless of their age or the nature of the crime, publicly register does not effectively protect the public from repeated offenses. Instead, MOAFR claims these public registries put offenders at risk of discrimination and violence and prevent them from rehabilitating and reintegrating into society safely.

MOAFR claims there are “well over 3 million wives, children, moms, aunts, girlfriends, grandmothers and other family members who experience the collateral damage” of the discrimination and violence that befalls low- and moderate-risk sex offenders with whom they have relationships. Due to the risk of their families experiencing this harassment, murder and other verbal or physical threats, many offenders are unable to reunite with the families like an offender of any other crime can. Thus, sex offenders often lack the community support system they need to reenter public life and be a productive member of society.

MOAFR also asserts that, because offenders are required to join the registry, often for life and regardless of what sex crime they have been convicted of, the compiled information does not actually highlight for the public who in their communities continues to be a real threat post-incarceration. For example, some offenders are required to register after urinating in public (termed indecent exposure) but are represented as posing a threat of sexual violence such as rape or molestation against their community.

Others can leave the registry after some time by filing a petition to be removed, but not many do so successfully. For example, MOAFR says some offenders are required to register after participation in a consensual “Romeo and Juliet” relationship, in which the age gap between the victim and the offender is small, but one participant is an adolescent and the other is an adult (such as a 19-year-old dating a 13-year-old). These offenders can file a petition for removal from the registry after two years, but approval is not guaranteed.

The nonprofit shared with BNG an essay by Ira Mark Ellman and Tara Ellman, “Frightening and High: The Supreme Court’s Crucial Mistake About Sex Crime Statistics,” published by the University of Minnesota Law School, they call “very important” to read. The essay details the statistical misconceptions that led to the production of such rigorous sex offender registration requirements.

Cited in multiple Supreme Court Cases is a 1988 statistic claiming the rate of recidivism (re-offense) for sex offenders is as high as 80%, which is much greater than the rate attributed to offenders of other crimes such as murder or arson. However, more recent research shows the rate of recidivism for low- to moderate risk offenders is somewhere between 2% and 7%, and most registrants fall in this category, as opposed to the smaller portion of high-risk offenders on the registry who are more likely to re-offend.

Given this information, MOAFR advocates for a revision to the sex offender registry requirements, aiming to produce a registry that clearly and reasonably represents the sex offenders who pose a threat of recidivism in their communities post-incarceration. Reducing the number of registrants on the list to only those most likely to re-offend, MOAFR claims, will help the sex offender registry be a more effective and accurate database, while also allowing offenders who are unlikely to re-offend the opportunity to properly rehabilitate and reintegrate into public life without risk of unnecessary discrimination and violence.

Members of the nonprofit believe these changes to the registry are reasonable and, if ever made in Missouri or in other states, not only protect the long-term rights of offenders post-incarceration but will ultimately contribute to a safer society at large.