Legislative and religious momentum is building to spare the life of a condemned Oklahoma inmate and to seek a moratorium — if not an outright ban — on the state’s capital punishment system.

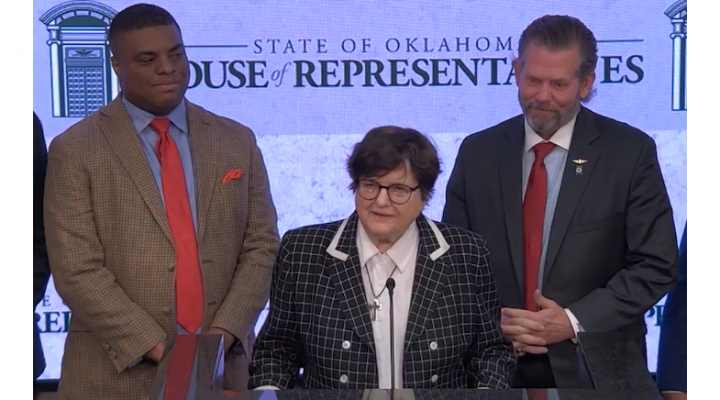

Lawmakers and a former parole and pardons official were joined in a news conference by faith leaders, including acclaimed death penalty opponent Sister Helen Prejean, at the Oklahoma statehouse May 4 to implore Gov. Kevin Stitt to issue a 60-day reprieve for Richard Glossip, whose fourth execution date in 26 years is scheduled for May 18.

The impassioned pleas followed recently disclosed information that the drug addict whose testimony secured Glossip’s capital sentence later recanted his accusations and had lied to jurors about his mental health disorder.

Gentner Drummond

That was enough to spur Oklahoma Attorney General Gentner Drummond, a Republican, to request clemency for Glossip from the state’s Pardon and Parole Board, which it denied last month, and then to ask the U.S. Supreme Court to issue a stay of execution on the grounds that the developments warrant a new trial in the case.

Republicans backing Drummond’s efforts described his moves as courageous and unprecedented and during the press conference urged Gov. Stitt to issue a two-month reprieve to give the high court time to decide on a stay of execution for Glossip.

Kevin McDugle

“The governor had said we’re going to follow the law. Let me point out a few things about the law,” said Rep. Kevin McDugle, who moderated the hybrid presentation. “By allowing this case to play out in federal courts now would be following the law. Following the law means not rushing the execution process. The state concealed evidence until Jan. 27 of 2023. These appeals could not have been brought sooner due to the state withholding evidence.”

Glossip was sentenced to death in the 1997 killing of his former supervisor, Barry Van Treese. Drug addict Justin Sneed admitted killing the man but accepted a life sentence in exchange for accusing Glossip of paying him to do it.

Recent examinations of the procedures and testimony in two trials have brought to light a range of issues that impugn the fairness of Glossip’s conviction, McDugle said.

“This new evidence the jury never heard due to the state’s concealment includes the recanting letters by Justin Sneed. It’s amazing to me,” he said. “We have letters where he says he wants to recant his testimony on Richard Glossip, but when the Court of Criminal Appeals looks at it, they said, ‘He really didn’t mean recant. He didn’t really mean what he wrote.’”

Sneed also lied under oath, McDugle said. “The state did not correct false testimony given by Sneed. And they knew it was false testimony. He testified falsely when he denied ever seeing a psychiatrist and being placed on lithium. Diagnosed with a serious mental health disorder, it made him prone to paranoia and violent outbursts.”

Faith leaders who addressed media used the occasion to pitch for either a more compassionate and fair criminal justice system or to end capital punishment altogether.

“I can’t stand by and let this happen,” said Prejean, the Catholic nun who achieved global fame through the 1995 film adaptation of her book, Dead Man Walking.

Prejean, who has agreed to accompany Glossip to his execution if it is carried out, said she opposes capital punishment because it is administered by human beings who are too imperfect to wield the power of life and death over others. Witnesses, victims, police and prosecutors are prone to making mistakes in high-pressure cases.

But in Glossip’s case, an additional motivation is the prisoner’s possible innocence given that both trials and unsuccessful appeals hinged on the testimony of a meth addict trying to avoid execution himself, she said.

“The question is, who deserves to kill them?”

Prejean said she understands support for capital punishment derives from perceiving killers as people who no longer deserve to live. “The question is, who deserves to kill them? And what kind of system are we going to set up in this state and all over?”

It is an especially unjust approach when it includes the execution of innocent people, she added. “We have set up a (death penalty) system we can’t handle as human beings. Basically, that’s what happened to Richard Glossip and that’s why we’re here.”

John-Mark Hart

Glossip’s plight is bringing together those who oppose and support capital punishment, said John-Mark Hart, pastor of Christ Community Church, a Baptist congregation in Oklahoma City.

“There are people involved with this statement, such as myself, who want to see an end to the death penalty in our state. We think we can find better, more redemptive ways to deal with even those who have committed the most grievous offenses. But there are also people who are part of this coalition who defend the death penalty in principle but say the way we’re practicing it here in Oklahoma right now is indefensible,” he said.

“As people of faith, we feel a responsibility to say, ‘Hey, we need to have a morally grounded dialogue about this.’ This can cannot be a merely political conversation. This is a human conversation. This is not a partisan conversation. This is a moral conversation about how we will treat one another as human beings.”

Demetrius Minor

And justice will not be served by Glossip’s death, said Demetrius Minor, a minister and national manager of EJUSA’s Conservatives Concerned about the Death Penalty project. “It doesn’t bring closure. It will not bring healing. It is the total opposite of turning the other cheek.”

Minor noted that nearly 200 falsely accused people have been released from American death rows since the early 1970s, creating an even more urgent imperative to spare Glossip and other condemned prisoners in Oklahoma.

“We also call upon the Legislature to place a moratorium on the death penalty. I ask you today: How many more Richard Glossip’s have to get our attention for us to finally realize this system is ineffective? The system is unjust. It is a failed policy for everyone. The risk of executing an innocent person is definitely real. We can’t afford to sit on the sidelines while a man may be killed in our name.”

McDugle said support is growing in the Oklahoma Legislature for averting the execution of a man who may be innocent. “More are saying we cannot kill this guy.”

If the governor does not issue a reprieve and the execution proceeds before the U.S Supreme Court can act, McDugle vowed legislation will be introduced to end the death penalty in Oklahoma.

Related articles:

Faith leaders call for urgent opposition to Oklahoma plan to execute an inmate a month for two years

The death penalty is dying a slow death; it’s time we pull the plug | Analysis by Stephen Reeves

Panel of faith leaders will raise awareness of death penalty injustice

American support for death penalty remains low, as new debates arise in Oklahoma, Ohio and Texas