I was recently forwarded, via WhatsApp, a video clip of my mother among some family members at a house opening ceremony in my hometown in Southern Nigeria. The video was shared by my beloved cousin, Vicki Egbo.

Having not physically seen my mother, Regina Akaeze, for more than five years, considering that we live thousands of miles away from each other, I was happy to watch the clip again and again. I liked what I saw.

For someone in her 80s, my mother isn’t looking that bad, I thought. Although she walks with the aid of a walking stick, which, for about a decade, has been her companion due to a dislocation she suffered from a fall, the situation could have been worse from the complications that resulted from the accident.

For someone in her 80s, my mother isn’t looking that bad, I thought. Although she walks with the aid of a walking stick, which, for about a decade, has been her companion due to a dislocation she suffered from a fall, the situation could have been worse from the complications that resulted from the accident.

I remember speaking to a doctor by phone about my mum’s condition months after she sustained the injury and he told me it was a risky situation and that, had the family not brought her to the hospital at the time we did, it could have resulted in her death. Prior to then, my mother had relied on traditional medicine and therapy for recovery.

Following that visit to the hospital, mother subsequently underwent surgery. And so, just like my father, Stephen Ezenweani Akaeze — the strong man until he gave in to ill-health and a few years later passed on — the fall took a toll on my mother. On different occasions, she reminded me, as if she was new to me, that she didn’t rely on anyone helping her with house chores. That’s my mum.

As a student of the University of Abuja, I paid tribute to my father in one of the stories that make up my book Amuzia and Other Stories. The title of the work is “My Father is Stronger than Me.” In it, I recall my father’s strength and athleticism that saw him in his old age indulge in as many press ups that I, his son could not match. My mum was not into that, but she was a strong woman in her own right until that day a slippery ground did her in.

Prior to the visit to the hospital, mum’s pain kept recurring. Even after the operation, she at times complained of tingling in her leg. On one particular occasion, I could not send her as little a sum as N10,000 (10,000 naira, which, at that time, was about $30). It was a time in my life in Lagos when my salary as a journalist was few and far between. That took a toll on me, and knowing how it equally affected my family, was devastating, to say the least.

“I would give anything for my mother, but here I was, unable to help.”

I would give anything for my mother, but here I was, unable to help. It was, as I told someone, the saddest moment of my life. To watch someone you love in pain is agonizing, and to not be in a position to help or do as much as you would want to, makes the pain worse.

All my adult life, it has been my joy and privilege serving my parents. With respect to my mum, it’s the least I can do to reward her love and service to the family.

From my early years in Jos, north central Nigeria, where I was born, and later, elsewhere, I remember my mother’s effort in assisting my father provide for the family. I remember her carrying food on her head to sell, walking far distances to do so.

In those days, Jos was devoid of ethnic or religious hate and animosity. It was a cosmopolitan town where Christians and Muslims lived together in peace and harmony. Jos of the early 2000s to now is defined by artificial boundaries separating Christian neighborhoods from Muslim ones, a result of ethno-religious clashes rooted in politics. From being a home of peace and tourism, as it was affectionately called, Jos and other parts of Plateau have became a cauldron of death and destruction of the worst kind.

At the age of 11, I left Jos to live with my newly married elder sister in the eastern part of the country.

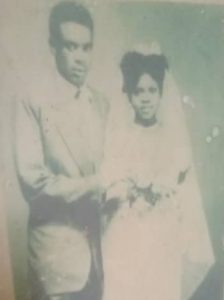

The author’s parents on their wedding day.

I missed Jos terribly, and when my mum once visited us, I could not hold back the tears when it was time for her to return home. Mum too, became emotional.

When we arrived at the bus station, where she was to board a vehicle to Jos, the person who drove us there, seeing my mood, asked rather childishly whether I had resolved to return to Jos. He simply didn’t understand.

Returning with the driver to my brother-in-law’s apartment after a difficult goodbye, I couldn’t get over the pain of being separated from my mother again.

My mum is not perfect. She’s, in fact, the opposite of my father — temperamental and easily provoked. Someone described her as fire, someone no one would want to toy with. Another said her kind is needed in every family.

How this fire met with water, which best suits my dad, and lived together with him until his death is one of the mysteries of this world.

As a mother, in terms of value and industry, my mum epitomizes a lot, and from my adolescent years, as my own way of repaying her love, I did imagine me caring for her as much as she has cared for me.

The love I have for my mother also shows in my interest in her interpersonal relationships. In this regard, I’m a sort of douser, the fire extinguisher who’s also not shy to say that as a true son of my mother, I could also lose my cool if provoked or pushed beyond a certain limit.

This is the way I put it to someone: “I think I take after my father and so my first instinct when I see trouble is to try all I can to avoid it. To run if I must. I will try all I can but when nothing works, my mother comes to life in me, and in that moment even I cannot tell how I may react.”

In my culture, we have a name that translates as “mother is supreme.” It’s evidently for a reason. Mother comes first.

Mother’s Day is significant, but like birthdays I’ve never celebrated, I do not wait until the day to shower love on the woman I love. Once, when I conversed with the brother of a woman I was dating, I told him. “I will treat her the way I treat my mum.”

I love you, Mama.

Anthony Akaeze is a Nigerian-born freelance journalist who lives in Houston. He covers Africa for BNG.