So many things should not have happened as they did. She should not have died alone in the hospital (as have so many others), suffocating from the ravages of COVID-19. I should not have had to say my final goodbye on Facetime – and then only through the kindness of nurses who connected us. She should not have lived her last weeks as she did, isolated and alone in a locked-down assisted living facility where I did not have access to see her or to effectively monitor the care she was receiving.

So many things should not have happened as they did. She should not have died alone in the hospital (as have so many others), suffocating from the ravages of COVID-19. I should not have had to say my final goodbye on Facetime – and then only through the kindness of nurses who connected us. She should not have lived her last weeks as she did, isolated and alone in a locked-down assisted living facility where I did not have access to see her or to effectively monitor the care she was receiving.

These things should not have happened. But my sister was a victim of a confluence of events – a devastatingly perfect storm of unfortunate timing, unwitting repercussions from the most carefully thought-out and well-intentioned decisions, a decline related to her underlying disease and the coronavirus pandemic, and inadequate care on the part of the facility where she spent the last eight weeks of her life. Her ensuing death has left me in the throes of anguish and grief complicated by my own feelings of remorse, guilt, despair and anger.

Nan and I lived 15 miles apart in metropolitan Atlanta. When she was diagnosed at age 72 with Parkinson’s and Lewy Body Dementia, I immediately took charge of her care. I made her a promise that we would walk together every step of the frighteningly inevitable path that lay ahead. Sadly, I was unable to keep that promise at the end.

“The disease has revealed preexisting flaws and failures across the entire industry of senior care.”

To her credit, Nan, who had been independent her whole life, allowed my sisterly intrusion into all aspects of her life. For the better part of three years, with some ups and downs, she was able to continue living in her own home with my close monitoring and help. But then the falls at home became more frequent. A fall on the last day of January landed her in the hospital for a week. When she was discharged eight days later, it was clear I could not manage her care on my own.

We had earlier made arrangements for her to move to a beautiful new assisted living facility. But it was awaiting licensure before it could open. So, scrambling, I found a facility that would accept her immediately for a month of respite care where she would likely stay only a short time before transitioning to the permanent facility.

Almost from the beginning, there were knotty issues that concerned me. I tolerated some of them, given that the facility had accepted Nan with very little notice. The first “e-call” button they gave her did not work. They replaced it, but it soon became apparent that response time to a patient’s call for assistance was often lengthy. There were times she would fall in the bathroom and pull the emergency call cord, only to tell me later that she would be on the floor quite a while before someone came.

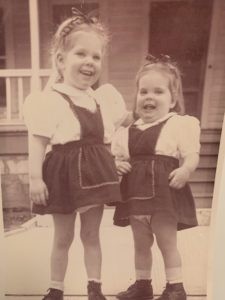

Clarissa and Nan (on right)

Throughout the rest of February and into March, I visited her daily, trying to make her as comfortable as possible, reminding her that this was all temporary. In early March, we were both elated when I got word from the new assisted living facility that they were almost ready to open. But then a glitch in her medications delayed her move a few more days.

Meanwhile, the coronavirus pandemic was spreading. With incredibly bad timing for us, assisted living and nursing home facilities were locked down and any move-ins were halted. Not only could my sister not move to the new facility – a huge disappointment for her – but I could no longer visit her where she was.

Our communication was limited to cell phone calls and the occasional Facetime conversation. As the weeks went by, I could tell Nan was declining. She lost her appetite. She spent more and more time on her bed, no longer participating in activities. She often would not answer her cell phone, telling me it was too hard to hold it up to her ear. She had frequent falls, many times having to endure an excessively slow response from staff.

Then came the day I was informed that Nan had developed a low-grade fever and a dry hacking cough – both symptoms of the virus. I asked if she should be tested for COVID-19 and was told that they “did not test there” and she would have to be transported to the ER. And if we did that, she would not be allowed back into the facility – something I later learned was not true.

“As we think of the precious seniors who enrich our lives and populate our churches, we who are people of faith must not wait on government oversight to change things.”

Some nine days later, I got a call about 8:15 p.m. from a caregiver that Nan had fallen and could not get up. I asked the staff member to hand Nan’s cell phone to her. As I talked to Nan, I assumed the worker had gone to get help. I asked to be notified as soon as they had gotten my sister up. I kept calling Nan to ask if help had come, and she would say “no.” This continued for 20 to 30 minutes. I was also frantically calling the front desk to get help, but each time got only the voicemail recording.

There was no “emergency number” I could call. Had I jumped in the car and driven to the facility, I could not have gotten in. It was a time of pure panic. Illustrating the thinness of nighttime staff, I was later told by an administrator that when patients fell, if they were not hurt, they were left on the floor until the medications were delivered and help could come. Emblematic of inadequate communication from the facility, it was not until a few days later, five days before her death, that I was informed she had lost 11 pounds over a very brief span.

After reluctantly agreeing that Nan needed to be transferred to the hospital, I was present at both the facility and the ER and watched as she was loaded and unloaded into and from the ambulance. She was cognizant and, from an agonizing distance, I waved to her.

The next day, her condition deteriorated at a dizzying pace. She died that night.

Our experience, though not atypical, drew the attention of a Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution, who was covering developments related to legislation introduced to the Georgia legislature. The bill, which has since been passed by both houses, called for sorely-needed and long-overdue senior care reform.

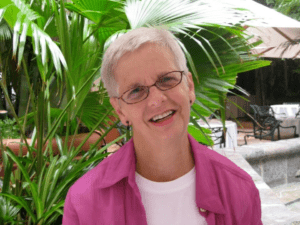

Nan Durrett

In Georgia, someone with a GED can manage a facility of 100 or more elderly residents. At night, one worker might be in charge of 25 people with dementia. I am sure these flaws are not unique to my home state. Low pay for caregivers (many of whom are persons of color), rampant turnover, poor training and staffing violations are endemic in the industry. Having more qualified care is essential, given the co-morbidities and frailness of residents. Often in these understaffed facilities new hires, needed immediately, are put into service with woefully inadequate training. That means strong nursing oversight must be available in all senior care facilities. In many facilities, as in the one that housed my sister, there is NO medical expertise on-site at night.

While these issues are also a challenge for many upscale facilities, I can only imagine the situations in places where persons with meager resources must seek care.

The pandemic has been catastrophic for senior care facilities and nursing homes. According to Forbes, as of June 16 more than 50,000 people connected to nursing homes or long-term care facilities have died from coronavirus outbreaks, representing more than 40 percent of COVID-19 deaths in the United States.

At the same time, the disease has revealed preexisting flaws and failures across the entire industry of senior care. And, not surprisingly, it has shed light on yet another area of American society that is plagued by systemic racial disparities.

“It shouldn’t have required a devastating pandemic to get our attention and to move community, government, industry leaders – and faith communities – to act.”

We must do more to care for the most vulnerable in our society. And that will not happen without the concerted efforts and robust advocacy of faith communities, including churches and nonprofit organizations. As we think of the precious seniors who enrich our lives and populate our churches, we who are people of faith must not wait on government oversight to change things. Many of these seniors are among the “least of these” among whom we are called to minister.

Would the changes necessary to address these flaws, proven in the crisis of a pandemic to be fatal for far too many senior adults, have prevented the death of my sister? Perhaps not. But it is something I wonder about. Would they have made her last weeks of life less painful and traumatic? Of that I have no doubt.

Meaningful reform, with the necessary resources and accountability, is the only thing that can help make sense of the sorrow borne by my family and so many others. That almost unimaginable number of 50,000 deaths includes one that is very personal to me. My loss has been extraordinarily painful, especially during these weeks of social distancing and isolation. I miss my sister every day.

It shouldn’t have required a devastating pandemic to get our attention and to move community, government, industry leaders – and faith communities – to act. But act we must.