Most pastors believe their education prepared them to address the trauma of grief caused by a death, but the majority say their training did not prepare them to address other forms of trauma, including public health crises and sexual assault. Only about half said they were trained to address the trauma caused by mental health crises, racial conflict, abuse and natural disasters.

These are among the key findings of a national survey on trauma and congregations conducted by The Center for Church and Community at the Diana Garland School of Social Work at Baylor University.

The survey gathered responses from 331 pastors and church leaders, asking about their knowledge of trauma, how often congregants came to them about certain types of trauma (pre-COVID and in the midst of COVID), how their education prepared them, and how competent they felt to address those situations. The survey also looked at how these church leaders experienced churchwide or collective traumas.

Erin Albin Hill, coordinator of research projects at the Center for Church and Community Impact, led the study along with Gaynor Yancey, director of the center.

Respondents represented a wide range of ages, included both men and women, and 82% were Baptist.

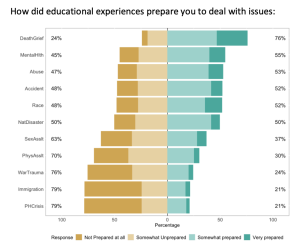

By far the issue these ministers felt most prepared to address by their education is grief surrounding death.

By far the issue these ministers felt most prepared to address by their education is grief surrounding death — one of the most common recurring traumas a pastor intersects on a regular basis. Three-fourths (76%) said they were “somewhat prepared” or “very prepared” for these moments, and only 24% said they were “somewhat unprepared” or “unprepared.”

From there, the survey found a steep drop off in educational preparation to address traumatic events. Bare majorities said they were somewhat prepared or very prepared to address mental health crises (55%), abuse (53%), accidents (52%), racial conflict (52%) and natural disasters (50%).

Only a third or less of respondents said they were taught to address trauma caused by sexual assault, physical assault, war, immigration, or public health crises.

Only a third or less of respondents said they were taught to address trauma caused by sexual assault, physical assault, war, immigration, or public health crises.

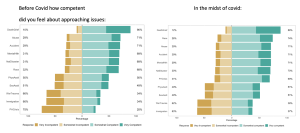

On a practical level, the survey asked these church leaders how their perceptions of their own confidence had changed from before COVID to today. The most dramatic finding was a 44-point gain in confidence to address a public health crisis. Before COVID, only 24% said they felt prepared or somewhat prepared for such conversations, but having experienced the worst global pandemic in a century, that number then rose to 69%.

Another event that overlapped with the pandemic also reshaped these ministers’ perceptions of their competence to give counsel amid trauma. Before the pandemic, respondents cited trauma around racial issues as the sixth thing in a list of options they felt most prepared to address. After two years of racial reckoning sparked by police murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor — among others — clergy confidence to address racial trauma rose to second on the list.

On most issues, clergy reported they feel more competent about their abilities than about the training they received in those areas.

On most issues, clergy reported they feel more competent about their abilities than about the training they received in those areas. For example, while only 55% said they received training on trauma related to mental health, 71% now say they feel at least somewhat prepared to address the issue.

Not surprisingly, clergy reported a significant increase in the number of conversations they had with congregants about public health crises, death and mental health issues during the pandemic as compared to before the pandemic.

“One interesting note with how often topics are discussed is that we know one in four women will experience sexual assault, but the data showed that 73% of respondents either talked about it annually or never,” Hill said. “So there’s a discrepancy in that data: Do people not feel safe discussing that type of trauma with pastors?”

Three-fourths of congregations reported experiencing one or more traumatic events throughout the last decade, spanning the range of issues surveyed but also reaching beyond that defined list. One of the collective traumas listed in the “other” option came from church conversations about LGBTQ inclusion. Also of note: About 10% of respondents said they had not experienced any churchwide traumas in the last decade. So either they didn’t see the pandemic as a collective trauma or did not believe it affected their church.

These traumatic events on the whole created more anxiety and depression for the respondents, some said. The events of the past three years also made some less secure in their vocational calling.

One respondent explained: “It made me realize I need more help, increased education, support needed in new areas.”

Another said they had felt a “profound sense of pastoral responsibility” and a “profound sense of pastoral inadequacy” at the same time, leading them to desire “better training in advance of future events.”

“In all, I interpret the data as very telling that pastors are having conversations about different types of trauma on a regular basis but aren’t necessarily prepared for it,” Hill said. “While not all were seminary trained, 84% of respondents were.

“One implication of the survey is that seminaries need to consider including content on trauma and trauma-sensitive care within their courses. From preaching to pastoral care, ministers need to know how to respond in an appropriate and honoring way when someone is discussing the traumatic experiences in their lives. Until that happens, pastors need to be learning about these topics either through independent study or attending trainings in order to be well prepared.”

Another important note, she said, is that “with every type of trauma listed, someone reported talking about that topic every day. When church leaders are having these conversations every day, it’s inevitable that church leaders will experience compassion fatigue and secondary trauma. This shows us that church leaders need to be proactive about taking care of themselves in order to stay healthy. I think we’ve already started seeing the byproduct of this with pastors leaving ministry at high rates.”

Related articles:

Why all congregational ministry should be trauma ministry | Opinion by Erin Albin Hill

After spiritual trauma, finding welcome in church once more | Opinion by Mallory Herridge

Seek to become a ‘trauma-informed congregation’ in November forward | Opinion by Bill Wilson