By Bob Allen

Ordained Baptist minister J. Dana Trent got more than she bargained for when she tried to broaden the field on a dating website application by checking boxes for other religions along with Christian and “spiritual but not religious” — a Hindu husband she says has brought her closer to Jesus.

Ordained Baptist minister J. Dana Trent got more than she bargained for when she tried to broaden the field on a dating website application by checking boxes for other religions along with Christian and “spiritual but not religious” — a Hindu husband she says has brought her closer to Jesus.

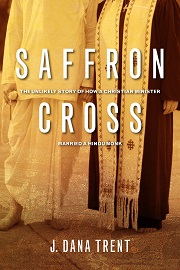

“As Christians, we may think we’ve cornered the market on God,” Trent writes in her new book Saffron Cross: The Unlikely Story of How a Christian Minister Married a Hindu Monk. “We cling to our religious traditions as the only true way to spiritual enlightenment or eternal life.”

Trent said the first seed for the book was planted in 2008, when she got engaged to Fred Eaker, an American-born Hindu convert who spent five years as a monk at a Gaudiya Vaishnava monastery in California.

Trent said the first seed for the book was planted in 2008, when she got engaged to Fred Eaker, an American-born Hindu convert who spent five years as a monk at a Gaudiya Vaishnava monastery in California.

As “self-described theology nerds,” she said, the couple sought out a manual for interfaith marriage. Finding volumes on Jewish-Christian and Muslim-Christian marriages but nothing close to the Baptist-Hindu variety, they joked: “Well, we’ll just right the book. How hard can it be?”

The idea became cemented when they honeymooned for two weeks in December 2010 in Vrindavan, India, described in vivid detail in the book’s opening chapter. That’s where sharing their story, and in turn fostering interfaith conversations, took on a new priority.

Returning home, Trent made plans to leave her full-time job in development at Duke University to pursue a career in freelance writing and teaching. She proposed Saffron Cross to Upper Room Books in November 2011. Upper Room accepted it for its Fresh Air Books imprint in April 2012, and she wrote and revised the manuscript in one year.

Trent says in the book that the human tendency is to “place God in a little box with sharp edges and straight lines.”

“Our biggest fear is that when we open ourselves to others’ understanding of God, we will jeopardize our own path,” she writes. “And yet, the opposite is true. The Holy Spirit breaks free from our human-made constraints and moves fluidly among us, crossing our unnecessary lines drawn in the sand.”

Fifty years ago, a mixed-faith marriage might have referred in the Bible belt to a Baptist wedding a Methodist, Presbyterian or even a Catholic. That’s a far cry from today, when young adults are surrounded by friends from many cultures and backgrounds, including those who practice other faiths.

Trent said she and her husband are hearing from a lot of Baptists and other evangelicals who identify with their story.

“On their college campuses, Millennials are surrounded by fellow students of different religions, faith traditions, and cultures — and many of them are choosing to date one another,” she said. “We’ve found that self-identifying Baptist/evangelical women particularly struggle with this.”

Several have come forward during book-signing events to discuss their non-Christian boyfriends. They often ask what to do with verses like 2 Corinthians 6:14, which says Christians should not be “unequally yoked” with unbelievers, as well as John 14:6, where Jesus says: “I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me.”

“They have difficulty reconciling such verses with the deep faith traditions they see exhibited in their boyfriends,” Trent said. “I always encourage them to read and exegete thoughtfully, considering the cultural and history contexts of the scripture — as well as the early formation of the church’s theology.”

“They have difficulty reconciling such verses with the deep faith traditions they see exhibited in their boyfriends,” Trent said. “I always encourage them to read and exegete thoughtfully, considering the cultural and history contexts of the scripture — as well as the early formation of the church’s theology.”

Trent said Christians “begin to stumble in interfaith conversation when we proof text.” She finds it more helpful to approach the situation from the viewpoint that “Christianity is absolutely the path for some, but not for everyone.”

“It’s difficult for me to deny the validity of the global traditions — given their rich history, scripture and most importantly their results,” she said. “The essential discernment is: does the faith path deepen the individual’s experience and relationship with God and their fellow humans? For me, that is the ultimate truth of religion.”

Trent admits she didn’t come to that conclusion overnight. Her own initial reaction to why her husband’s childhood profession of faith in Christ didn’t last was because his pastor didn’t follow up by insisting upon his baptism.

One thing Trent said struck her early on about her husband’s devotional life was Hinduism’s focus on “what can I do for God?” rather than the individualistic evangelical concern of “what can God do for me?”

Trent grew up in Binkley Baptist Church in Chapel Hill, N.C., a progressive congregation known as a safe haven for folks who didn’t belong anywhere else. Her spiritual nurture also included a Southern Baptist church that ordained her to the gospel ministry despite the Southern Baptist Convention’s official stance that the role of senior pastor “is limited to men as qualified by Scripture.”

She enrolled at Duke Divinity School, finding her place as a Baptist among United Methodists at the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship-affiliated Baptist House of Studies led by Baptist theology professor Curtis Freeman.

Trent acknowledged that a lot of Christians are uncomfortable talking about things like sexual orientation and interfaith dialogue.

“At some point, it is my fear that Christianity will lose an entire generation of practitioners,” she said. While young people “are waiting for the church to sort out its views on gender, sexuality and interfaith unions, their reality is that their friends are from many cultures and backgrounds, some are LGBT, and some practice other faiths.”

“They know and love their friends — so it’s impossible for them to understand and reconcile why the church doesn’t accept them, too.”