Fear swept through the African immigrant community in Ohio when Donald Trump took office in 2017 and vowed to implement mass deportations and other hardline anti-immigration measures, activist Demba Ndiath said.

Even longtime U.S. residents without criminal offenses grew increasingly concerned as immigrants with minor documentation issues or expired visas were detained and summarily deported to the countries they once fled, said Ndiath, an organizer with the Ohio Immigrant Alliance who had a family member deported to Mauritania.

“We woke up during the Trump era all being scared. Even those who had paperwork thought we could be targeted because of the color of our skin. Some of us were pulled over on the road and taken to jail before being able to verify if we had correct paperwork,” he said during a recent press briefing organized by the Immigrant Alliance and the Center for Law and Social Policy.

“It was even difficult to go to the mosque and pray, which is one of our religious obligations. I remember, one by one, seeing people missing from our mosque leadership and hearing some of them are in Canada, others went back to Africa voluntarily and others were in jail,” he recalled. “People who never committed any crime, never killed anybody, never caused any domestic violence or any traffic violation — their dreams were cut short by the Trump administration.”

Lynn Tramonte

The media event was held on Capitol Hill to promote Broken Hope: Deportation and the Road Home, a new book by Lynn Tramonte and Suma Setty. The book, which was delivered to members of Congress the same day, presents interviews with 255 deportees sharing the trauma suffered in being forcibly separated from family and communities.

The book’s distribution is part of the Alliance’s #ReuniteUS campaign to bring deportees back to the United States.

Most of the subjects in the book are Muslim men deported to Africa after living years or decades in the U.S.

“They paint a stark picture of how the U.S. immigration system wages lasting and unnecessary damage on ordinary people. Many have horrific stories about the ways they were treated in so-called immigration jail and deported — often in shackles,” write Tramonte and Setty.

Suma Setty

Tramonte serves as director of the Ohio Immigrant Alliance and Setty as senior policy analyst with the Center for Law and Social Policy.

“Despite doing everything they could to avoid this nightmare, they left a large piece of themselves in the United States — homes and jobs; families, friends, communities, co-workers, neighbors, clients, bosses, employees and Ummah (community). They want you to know that deportation is an extreme consequence for a visa violation. Deportation took the heart of their relationships. It took their sense of safety and peace. The U.S. is home and they want to return.”

Many were deported after workplace raids by Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents. Others initially were detained in traffic stops or during routine ICE check-in visits.

Broken Hope also documents the effect deportations have on families left behind in the U.S., including the longer hours spouses must work to offset lost income while also supporting those deported. One of the men interviewed relayed that his wife “‘has to support us by herself. She has to pay the mortgage. I can’t provide for my kids or protect them. What is going to happen if I’m not there?’”

Tramonte and Setty delve into the blatant racism that animated Trump’s immigration strategies, noting his reference to African nations and Haiti as “shithole countries” and to his open animosity toward Muslims and immigrants of color.

Deportations to Africa shot up 74% and to the Caribbean by 48% under Trump.

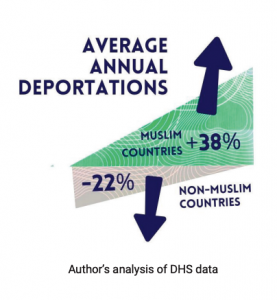

“Average annual deportations to Muslim-majority nations also increased by 38% during the Trump administration.”

“Average annual deportations to Muslim-majority nations also increased by 38% during the Trump administration, while deportations to non-Muslim countries decreased by 22%.”

During Barack Obama’s presidency, deportation enforcement was directed at immigrants who posed border security, public safety or national security threats. Trump rescinded that policy in favor of one that did not prioritize candidates for deportation, Tramonte and Setty explain.

“Suddenly, anyone eligible for deportation became a target for ICE” including those interviewed for the book and others “who had been in the country for years or even decades and regularly reported to ICE offices for a status review. Previously, as long as they continued to touch base with ICE when required, they were not considered priorities for deportation. That changed immediately under the Trump administration’s executive order.”

“Suddenly, anyone eligible for deportation became a target for ICE” including those interviewed for the book and others “who had been in the country for years or even decades and regularly reported to ICE offices for a status review. Previously, as long as they continued to touch base with ICE when required, they were not considered priorities for deportation. That changed immediately under the Trump administration’s executive order.”

President Joe Biden instituted a policy similar to Obama’s and added deportation protections and access to work permits for eligible immigrants. But the authors call for the current administration to go further by instituting a process of re-admission for those deported during the Trump era.

“Instead of letting this injustice stand, the administration should use its authority to bring them home,” Broken Hopeargues. “Instead of fearing the political consequences of generous return policies, officials in the executive branch should recognize that establishing a path to return is a humane, family-oriented and positive act that will benefit people who lived in and contributed to the U.S. for decades, as well as their family members, including many U.S. citizens.”