A recent book about the first Baptists in Kentucky reveals present-day Baptists face many of the challenges that vexed their 18th and 19th century ancestors, Aaron Coyle-Carr said during an online discussion presented by Baptist History and Heritage Society.

“The more I read through this book, the more I realize the themes that reverberate into the present in some really powerful ways,” said Coyle-Carr, pastor of First Baptist Church in Morehead, Ky. He was responding to historian and author Keith Harper’s presentation of his book, A Mere Kentucky of a Place: The Elkhorn Association and the Commonwealth’s First Baptists. The conversation was part of the society’s “Making Baptist History Public History” webinar series.

Aaron Coyle-Carr

Coyle-Carr noted divisions between early Kentucky Baptists over race, paid-versus-unpaid clergy, generational disputes, and the value and authority of associations, among other issues, are still pressing issues today. “Most of our churches, associations, denominational bodies and other kinds of Baptist-adjacent organizations are still grappling with a lot of the things that these Elkhorn Baptists were grappling with.”

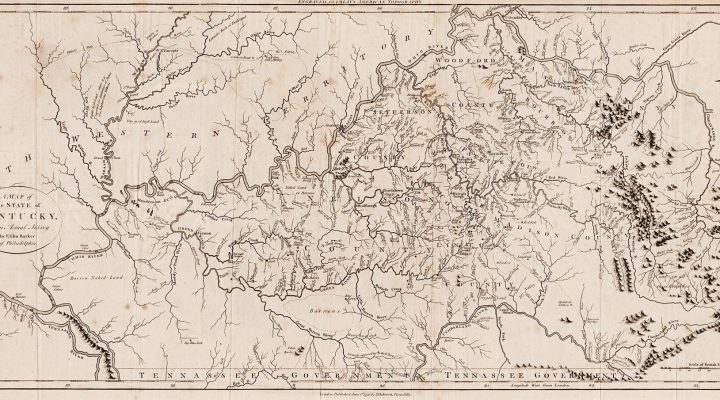

Constituted in 1785, Elkhorn was the first Baptist association in Kentucky. Its first history, published in 1876, was written by Basil Manly Jr., one of the founders of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Ky.

Geographically, the association stretches northwest from Lexington to Frankfort in a portion of north central Kentucky. At times in the past, the association stretched as far north as southern Ohio. Manly described it as “the earliest organization of the kind in Kentucky, or in the region west of the Alleghanies.”

The historic association in 2014 changed its name to Central Kentucky Network of Baptists.

Keith Harper

The most controversial finding of the new book is that economic gain rather than religious freedom motivated the association pioneers to migrate to Kentucky during the late 1700s and early 1800s, said Harper, senior professor of Baptist studies at Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary in North Carolina.

“These early men were looking to make money. They came from Virginia. They moved into Kentucky. They saw an opportunity to become wealthy. They saw an opportunity to become powerful and they seized on that opportunity. And that’s all there was to it,” he explained.

Two leading examples of that trend were Baptist ministers and brothers Elijah and Louis Craig, both of whom had been jailed in Virginia before moving to Kentucky.

“The Craigs were among the commonwealth’s largest land speculators, so you go from persecuted preachers to land barons or wannabe land barons,” Harper said. “And if you look in the early land claim books of Kentucky, you’ll find that at one point the Craigs … claimed nearly a quarter of a million acres. That sort of changes your view on the persecution narrative.”

Elijah Craig was a Baptist pastor who is credited with inventing bourbon whiskey.

Support for the enslavement of human beings was another defining characteristic of Kentucky’s first Baptists, Harper said. “I found that slavery was vitally important in defining Elkhorn’s identity.”

One of the association’s leading founders, preacher John Taylor, owned around a dozen slaves when he migrated to Kentucky in 1785. Another example came in a high-profile, 19th century case involving a pastor refusing to pay one of his church members for a slave after the slave died, splitting the congregation and the Elkhorn Association.

“And guess what: They brought charges against the preacher,” Harper said. “They brought charges at the association level like it was a court, and the association says, ‘We just don’t see how you can bring charges against your preacher here.’”

Harper said it’s also important to note that most members of the association were military veterans of the Revolutionary War, a campaign waged on the proposition that all human beings are created equal, and to guarantee economic and religious freedom. The Baptists of the association, however, “did not believe that African Americans were created equal and they turned their backs on ministers like David Barrow.”

Barrow was a Revolutionary War veteran and church pastor who had been persecuted for his Baptist faith in Virginia before freeing his slaves in 1784 and publishing a booklet arguing against the institution of slavery, Harper said. “If you want to defend slavery as an institution, read that booklet and see if you can still do it. And to his credit — to his eternal credit — David Barrow paid for the publication of that book out of his own funds. He paid for it, he gave it away for free and it fell on deaf ears.”

“They took the unprecedented step of actually going to David Barrows’ church on the day they were having services and tried to get him voted out of his own congregation.”

Barrow became a pariah in the Elkhorn Association in the process, he added. “They took the unprecedented step of actually going to David Barrows’ church on the day they were having services and tried to get him voted out of his own congregation — against Baptist polity, against anything that Baptists say they believe. But that’s the lengths to which they were willing to go.”

Disagreements over whether pastors should be paid or self-funded and over missions versus revivals were among other points of contention within the association, Harper reported. “They were squabbling for one reason or another. They could not get along with one another, and those problems persisted well into the 19th century. One schism after another. One group leaving after another.”

Divisions sometimes emerged around generational lines, he added. “You had a younger group of folks who came by, and they were not tied to the old ways, and they went their own way, and the association then is in real trouble.”

Baptist life is in much the same condition today, Harper said. “Fundamentally, how different are we really when we can’t get along over issues that should unite us, rather than divide us? Things that seem simple and straightforward tend to be things that get blown into huge proportions. They’re blown out of proportion. And ultimately, they bring schism. So, we’re not so different after all. They may have been 200 years ago, but they read like something that would fit conveniently today.”

Coyle-Carr said there is something reassuring in the similarities between the two eras of Baptist life. “I find it encouraging because it suggests these are perhaps not questions that ever can be resolved, that every generation has a responsibility to grapple with Scripture, and wrestle with it and find new meaning. It’s almost as if every new generation of Baptists has a responsibility to grapple with these questions.”

Related articles:

MLK’s civil rights work was an outgrowth of his Baptist tradition, author explains

Knowing a church’s history on slavery can be a nudge toward redemption, historians say

Author explains the history of ‘Peace Be Still’ and its social influence

Scholar traces how Black churches became centers of political engagement