A federal judge’s June 21 ruling to protect former Trump administration officials from lawsuits stemming from their actions to forcibly clear Lafayette Square on June 1, 2020, illustrates the near-impossibility of any government official being held responsible for acting in ways that for any other citizen would be considered illegal.

The ruling against Black Lives Matter protesters and others removed from Lafayette Square so then-President Donald Trump could have a photo opportunity in front of a church goes to the heart of a question critics of the former president have asked at multiple junctures: Why has no individual ever been held accountable for enacting cruel policies demanded by Trump or his high-level officials?

This question relates to federal employees who enacted the administration’s child-separation policies at the southern border, to those who mistreated and in some cases abused immigrants held in detention, as well as to a host of other instances where federal officials infringed on the civil liberties of those who disagreed with the president.

“Why has no individual ever been held accountable for enacting cruel policies demanded by Trump or his high-level officials?”

The answer is a court doctrine of “qualified immunity” that provides blanket protection to government employees — as well as law enforcement — for actions they take in their official capacities. According to this idea spelled out by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1984, most government employees are immune from personal prosecution for actions they take.

This complicated and controversial practice has been challenged by those on the right and the left in American politics, leading some nonpartisan groups to call for legislative reform and clarification.

Among those is the Center for American Progress, which has declared: “Comprehensive reform is needed to correct the severe imbalance that has closed the doors of justice to people across the country who have had their civil rights violated by government officials and to breathe life into the rights and liberties guaranteed to individuals by the U.S. Constitution and federal law.”

The Lafayette Square case

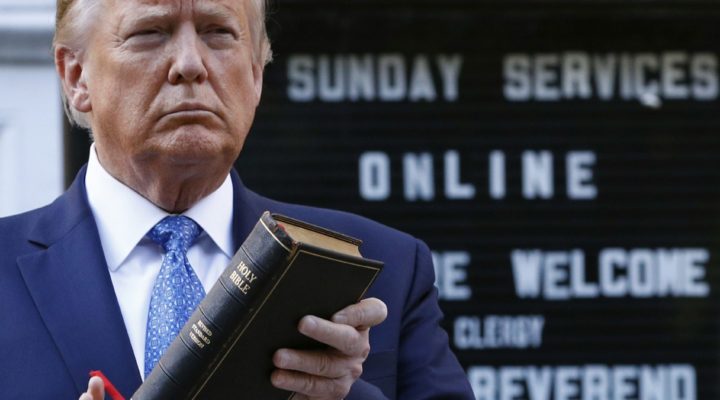

In what turned out to be one of the most iconic presidential photos of all time, Trump and some of his advisers famously walked the short distance from the White House to Lafayette Square, where Trump stood in front of St. John’s Episcopal Church and held up a large black Bible.

This happened on a summer day as the square was filled with Black Lives Matter protesters and others critical of the president’s record on race — and amid the backdrop of a spring and summer filled with a string of police killings of Black citizens, including George Floyd in Minneapolis.

On June 1, 2020, then-President Donald Trump departs the White House to visit outside St. John’s Church, in Washington. Walking behind Trump from left are Attorney General William Barr, Secretary of Defense Mark Esper and Gen. Mark Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. (AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

In order to give the presidential party clear passage, law enforcement officers acting on orders from the White House used tear gas and other riot control tactics to forcefully remove peaceful protesters from the square and the adjacent church. Church officials were not consulted.

Before visiting the church, Trump had given a speech urging governors to put down Black Lives Matter protests by using the National Guard to “dominate the streets.” If they did not, he said, he would “deploy the United States military and quickly solve the problem.”

The day’s events were widely panned as pandering to Trump’s religious base and using excessive force to do so — as well as violating basic First Amendment rights to freedom of speech and freedom of religion.

General Mark Milley, who was then chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, apologized for his role in the photo op. Law enforcement leadership involved in the events gave an array of explanations to justify their involvement, including an appeal to national security.

Ultimately, four overlapping lawsuits made their way to federal court, where they were combined under the jurisdiction of U.S. District Judge Dabney Friedrich, a Trump appointee. The plaintiffs, represented by the American Civil Liberties Union, alleged that Trump, Attorney General William Barr and an array of other officials conspired to violate the civil rights of the protesters.

Citing the doctrine of qualified immunity, the Biden administration Justice Department was among multiple claimants urging Judge Friedrich to dismiss the combined cases.

The ruling

In a 51-page ruling, Judge Friedrich did just that, with two small exceptions. She allowed that certain claims against Arlington County and D.C. officials may proceed, as well as a claim regarding continued restrictions on access to Lafayette Square.

Within the heart of the ruling, Friedrich found that the defendants did not have standing to bring most of the charges they outlined, but she also appealed to the doctrine of qualified immunity for the federal officials. She also ruled that there does not appear to have been a “conspiracy” against the protesters, as they had alleged.

She further affirmed the defendants’ appeal to national security as justification for impinging on the free-speech rights of the peaceful protesters.

Additional Supreme Court rulings have all but gutted the possibility of achieving a successful claim.

Key to this ruling is an understanding of a 1971 Supreme Court case called Bivens v. Six Unknown Named Agents of Federal Bureau of Narcotics. Typically known as Bivens for short, plaintiffs such as the Black Lives Matters protesters often are said to have filed a “Bivens” claim, or the court may speak of claims meeting a “Bivens” test.

In that case, the Supreme Court recognized the ability of individuals to bring claims for damages against federal officers in certain circumstances. In so doing, the court outlined certain standards for such claims.

In the intervening 50 years since Bivens, however, additional Supreme Court rulings have all but gutted the possibility of achieving a successful claim. And, as Judge Friedrich noted in her June 21 decision, “the Supreme Court has never extended Bivens to a claim brought under the First Amendment.”

Where the law stands now

This is the point at which a discussion of whether citizens or others may successfully file suit against government employees get exceptionally complicated — even though the basic answer is “no.”

Two competing court doctrines are at work here. One is qualified immunity, which extends blanket protections to government employees and over time has grown broader and broader. The other is the Bivens test, which provides certain circumstances in which claims may be brought against government employees and over time has been growing narrower and narrower.

To get to the current situation, we have to travel back to 1871, when as part of a Reconstruction-era civil rights act, a law was passed known as Section 1983. At the time, state officials in the American South, resisting Reconstruction and clinging to the Lost Cause theory, were collaborating with the Ku Klux Klan to terrorize Black citizens. This federal law established a right of individuals to sue government officials who violated constitutional rights even if acting under the influence of state or local laws.

That set the stage for a 1982 Supreme Court ruling called Harlow v. Fitzgerald, in which the qualified immunity doctrine was created by the court and imposed on Section 1983.

In Harlow, the court defined qualified immunity as protecting government officials from frivolous suits. Four years later, the court’s own interpretation of this doctrine had broadened to the point that it declared that it “provides ample protection to all but the plainly incompetent or those who knowingly violate the law.”

“As the doctrine evolved, it became clear that it provided a shield against accountability even in cases of shocking civil rights violations.”

At that point, court precedent required that federal courts determine whether a Constitutional right had been violated when granting a defendant protection from liability through qualified immunity. But even that requirement fell in a 2009 case called Pearson v. Callahan. Among other effects, this discouraged lower courts from labeling any conduct by government officials as unlawful.

As American Progress reports it: “As the doctrine evolved, it became clear that it provided a shield against accountability even in cases of shocking civil rights violations.”

Qualified immunity may be best known as a defense against litigation involving law enforcement officers. This has been a focus of many of the protests against police brutality and the murder of innocent Black citizens, for example.

However, the same legal doctrine that shields police officers and federal agents also shields federal employees such as William Barr acting in his capacity as attorney general in the Trump administration. Just as it also shielded Homeland Security and Border Patrol employees in their mistreatment of immigrants.

The shield even extends to private entities carrying out work under government contracts.

Licensed to kill

For more than 30 years, the Supreme Court has declined to take up additional cases that would provide opportunity to further interpret or clarify Bivens. Which has left in place a mandate from the court that Bivens should not be applied to “any new context or new category of defendants” not already narrowly addressed by the court.

This came into play with a 2020 Supreme Court ruling called Hernández v. Mesa. In that case, a U.S. Border Patrol agent on June 7, 2010, shot and killed a 15-year-old Mexican boy. The agent who fired the fatal shot was standing on the U.S. side of the border; the teen who was killed was standing on the Mexico side of the border. The agent claimed the boy was part of an illegal border crossing attempt; the boy’s parents claimed he was playing a game with friends where they ran back and forth through a culvert separating Ciudad Juarez from El Paso.

The boy’s parents brought a case against the agent in U.S. court after the U.S. refused to extradite the agent to face trial in Mexico. The case wound its way through U.S. courts for more than nine years, culminating in a Supreme Court ruling on Feb. 25, 2020.

Advocates for reform expressed frustration that the Supreme Court, which created the no-new-contexts rule, refused again to define the appropriate contexts for Bivens claims to be made.

The high court ruled that the family could not bring a Bivens claim against the agent because of the precedent laid down by the court saying such protections cannot be applied to a “new context.” The court said this case involved a “new context.”

Advocates for reform expressed frustration that the Supreme Court, which created the no-new-contexts rule, refused again to define the appropriate contexts for Bivens claims to be made.

“As the Supreme Court has explicitly refused to say what types of claims would constitute a ‘new context’ and what types of ‘special factors counselling hesitation’ would militate against extending the Bivens remedy to such new contexts, federal courts have been given tremendous leeway to bar suits from going forward, and the Supreme Court and U.S. Courts of Appeals have frequently reversed lower courts that have allowed such claims to proceed,” warned American Progress.

What can be done?

It’s not just the Center for American Progress — an organization that, as its name implies, promotes “progressive” ideas — that thinks the doctrine of qualified immunity needs to go. So does the libertarian Cato Institute.

In September 2020, Cato Research Fellow Jay Schweikert wrote a treatise slamming qualified immunity, calling it a notion “invented by the Supreme Court” and “one of the most obviously unjustified legal doctrines in our nation’s history.”

“Qualified immunity has also been disastrous as a matter of policy,” he wrote. “Victims of egregious misconduct are often left without any legal remedy simply because there does not happen to be a prior case on the books involving the exact same sort of misconduct. By undermining public accountability at a structural level, the doctrine also hurts the law enforcement community by denying police the degree of public trust and confidence they need to do their jobs safely and effectively.”

His solution? “Complete abolition of qualified immunity.”

Also in September 2020, George Mason University law student Dawson Weinhold, who identifies as a Republican, wrote for the university’s Fourth Estate journal, explaining why Republicans should be the first to dislike qualified immunity.

“If we Republicans are the party of personal responsibility, we shouldn’t carve out exceptions in the law for government officials.”

“Abolishing qualified immunity checks the right boxes for Republicans to support it,” he wrote. “It would make law enforcement officers more responsible to the people they serve by removing incentives to ignore civil liberties, and it would push back against judicial activism. If Republicans want to be pro-police, they should have faith in the police’s ability to uphold civil liberties. If we Republicans are the party of personal responsibility, we shouldn’t carve out exceptions in the law for government officials.”

But, he noted, for now the debate about qualified immunity continues to be driven by political differences on policing and police reform.

Vox and Data for Progress took a national poll in April 2021 to assess Americans’ attitudes on various aspect of policing. In one question, the pollsters described qualified immunity as a doctrine that “makes it extremely difficult to sue government officials — including police — for actions that are unconstitutional or illegal that they performed in their official capacity.” They then asked respondents if they favored ending this practice.

The results: 73% of Democrats, 59% of independents and 59% of all respondents supported getting rid of qualified immunity, while only 46% of Republicans did.

Republican legislators, meanwhile, have expressed varying degrees of willingness to consider at least some modification or restriction on the doctrine of qualified immunity through legislation.

The “George Floyd Justice in Policing Act” passed by the U.S. House of Representatives on March 3, 2021, has yet to come up for a vote in the U.S. Senate, where it faces threat of filibuster by Republicans. This act includes new restrictions on the use of qualified immunity for police officers, which has been described as a “non-starter” by Republican leadership.

For now, government officials remain shielded by a court doctrine that never has been passed by Congress as a law and that has become a symbol of opposing views on police reform.

Related articles:

Jury awards $2.3 million in pastor’s wrongful death

You might have missed this, but the Supreme Court just opened a new term

Trump’s latest obscenity, a contrived and vacuous photo op, has left a lasting impression | Opinion by Michael Friday