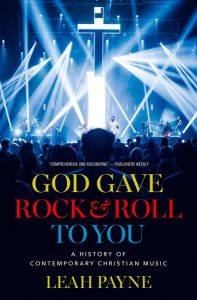

“What can one learn about the development of evangelicalism by looking at CCM, one of the largest, most profitable forms of mass media produced in the 20th century?” asks Leah Payne in her new book, God Gave Rock and Roll to You: A History of Contemporary Christian Music.

It turns out one can learn a lot from Payne, associate professor of American religious history at Portland Seminary, and from her analysis of how Contemporary Christian Music has served as “the soundtrack of evangelical conversions, worship, adolescence, marriage, child-rearing, and activism” and helped “disseminate evangelical messages about what it means to be Christian and American.”

It turns out one can learn a lot from Payne, associate professor of American religious history at Portland Seminary, and from her analysis of how Contemporary Christian Music has served as “the soundtrack of evangelical conversions, worship, adolescence, marriage, child-rearing, and activism” and helped “disseminate evangelical messages about what it means to be Christian and American.”

Payne knows the industry, its artists and its executives, quoting many key players alongside some of the 1,263 fans who filled out her questionnaire on “Contemporary Christian Music: A Survey.” She’s insightful in explaining the ways CCM “enforced strict evangelical ideals about gender, sexuality, race, ethnicity and class.”

Leah Payne

The daughter of a Pentecostal pastor, she married a Christian musician and moved to Nashville in 2001, “when CCM was at its pinnacle in terms of prosperity and cultural influence.” She later worked for Charlie Peacock, one of the genre’s most creative and influential artists, and hosts two podcasts: “Weird Religion” (about religion and popular culture) and “Rock That Doesn’t Roll” (about Christian rock).

Payne’s history is sweeping. She highlights key figures in CCM’s birth, including Ralph Carmichael, who began writing music for Billy Graham movies in the 1950s, and Southern Baptist youth pastor Billy Ray Hearn, who helped create Good News: A Folk Musical in the 1960s and would go on to launch Sparrow Records in 1976.

Billy Graham and Bill Bright of Campus Crusade for Christ teamed up for Explo ’72 in Dallas, putting their seal of approval on a “religious Woodstock” that introduced Larry Norman and other artists to a crowd of some 75,000 followers.

Graham and Bright were among the earliest evangelical leaders to see CCM as “spiritual vitamins” for white suburban youth, and they would inspire others who saw CCM as a means to “save young souls and shape the nation through music.”

Early Jesus music emerged from “coffeehouses, on college campuses, and at beachside church services up and down the West Coast,” presenting a picture of Christ as “a gentle, loving Savior who above all desired intimacy with his people.”

While earlier church musicals “depicted hippies as moral degenerates living in rebellion to God,” “Jesus People saw the counterculture as, to borrow a biblical phrase, a field white unto harvest.” Their early version of CCM portrayed Jesus as “a rebel revolutionary — the ‘ultimate hippie’ — who disrupted the principalities and powers of the world with the good news” of the kingdom of God.

While earlier church musicals “depicted hippies as moral degenerates living in rebellion to God,” “Jesus People saw the counterculture as, to borrow a biblical phrase, a field white unto harvest.” Their early version of CCM portrayed Jesus as “a rebel revolutionary — the ‘ultimate hippie’ — who disrupted the principalities and powers of the world with the good news” of the kingdom of God.

As CCM quickly grew in popularity and profitability, major Christian labels were sold off to secular corporations, which worked to create crossover superstars like Amy Grant.

“If Grant was the evangelical Barbie of CCM, … Michael W. Smith was the complementary Ken doll.”

“If Grant was the evangelical Barbie of CCM, the unattainable ideal of beauty and virtue of her generation, her friend and collaborator Michael W. Smith was the complementary Ken doll,” Payne writes.

Personality and celebrity would play a growing role. Teen girls could idolize CCM artists like Point of Grace, CeCe Winans, Crystal Lewis, and Nicole C. Mullen, who offered inspirational alternatives to their more famous secular counterparts.

Personality likewise would become a bigger force in the growing worship music market as bestselling artists (Michael W. Smith, Petra, Delirious?, Sonicflood, Passion, Chris Tomlin, and David Crowder) transformed the liturgical language of America’s megachurches with a rock-oriented style of worship music while topping sales charts in CCM Magazine.

Personality likewise would become a bigger force in the growing worship music market as bestselling artists (Michael W. Smith, Petra, Delirious?, Sonicflood, Passion, Chris Tomlin, and David Crowder) transformed the liturgical language of America’s megachurches with a rock-oriented style of worship music while topping sales charts in CCM Magazine.

Today, what’s left of the CCM industry gets most of its revenue from licensing worship songs to congregations, a revenue stream that makes up for the collapse of the Christian bookstore industry, “the longtime cultural hub of white evangelical entertainment.” Payne says the collapse was “an incalculable loss for the (CCM) industry.”

Other pressures on the industry include the decline in church attendance, which has hurt both the concert and festival circuits, and Christian radio’s shift from music to conservative political talk, exemplified by the Salem Media Network.

Payne shows how evangelicals exploited attractive female artists, including Southern Baptist beauties Britney Spears and Jessica Simpson, to promote purity culture, with mixed results.

The pressure on female artists was intense — be sexy enough to sell, but not sexy enough to incite males’ lust. Even though some of the purity exemplars failed to follow through on their public pledges, the message still resonated with many fans.

Payne tells the story of a CCM fan who embraced sexual purity in the 1990s thanks in part to a CCM artist who endorsed a popular Christian book by Joshua Harris at her concerts. Harris (who has since renounced the book and apologized for the harm it caused) said Christian teens should skip dating and engage the opposite sex only through courtship relationships that are closely monitored by parents.

“I remember going to a Rebecca St. James concert where she extolled the virtues of I Kissed Dating Goodbye. My youth pastor later castigated us for being so enthusiastic about it, because he had been teaching us the same thing for months and to his mind none of us had taken his advice to heart.”

“I remember going to a Rebecca St. James concert where she extolled the virtues of I Kissed Dating Goodbye. My youth pastor later castigated us for being so enthusiastic about it, because he had been teaching us the same thing for months and to his mind none of us had taken his advice to heart.”

The Jesus Music, a 2021 film about CCM, briefly touched on the issue of race, why CCM is so white, and why Black artists can’t catch a break. Payne goes deeper, examining historic roots: “Segregation goes back to the industry’s earliest days. CCM grew out of early 20th-century white revivalism. The network of predominantly, if not exclusively, white churches, camp meetings and Bible colleges served as the tracks upon which CCM would travel the nation.”

Payne also shows how CCM audiences have long been exploited for political purposes.

“Much of the top-selling CCM aimed at adults reflected the idea that American patriotism and social conservatism were synonymous with Christian orthodoxy,” she writes: “Ray Boltz’s 1994 ‘I Pledge Allegiance to the Lamb’ epitomized this blend of 1990s nationalism and premillennial dispensationalist angst. The music video featured a Christian father and son, persecuted for confessing Jesus Christ, mourning the 1962 Supreme Court decision banning sponsored prayer in public schools and ‘political correctness’ as inciting incidents of the apocalypse.”

Ray Boltz

Boltz later came out as gay, ending his CCM career. He now performs at LGBTQ-friendly churches.

Carman, meanwhile, represented “a growing set of performers who offered theatrical alternatives to mainstream entertainment.” His schtick “relied on broad, stereotypical masculinity to create cosmic battles between Satan and the Lord.”

Carman, meanwhile, represented “a growing set of performers who offered theatrical alternatives to mainstream entertainment.” His schtick “relied on broad, stereotypical masculinity to create cosmic battles between Satan and the Lord.”

Carman, Michael W. Smith, and Michael Tait have promoted Trump, but no CCM artist is more MAGA than former Bethel star and “Worship Protest” artist Sean Feucht. He’s not great at music but he’s adept at “harnessing the political fervor of the COVID- 19 era (and has) styled himself as a ‘worship-protestor’ who resisted health restrictions” during his nationwide “Let Us Worship” tour.

CCM continues to inspire activists in surprising ways. The Newsboys’ version of the song “God’s Not Dead” was a million-selling 2011 culture war anthem that inspired a book and a movie.

The song also was blared over loudspeakers by a group of people dancing and blowing shofars outside the U.S. Capitol as hundreds of rioters attacked and entered the building on Jan. 6, 2021.