After three weeks of chaos, the Republican majority in the House of Representatives finally elected a new speaker — Mike Johnson of Louisiana’s 4th Congressional District. While Johnson has served in Congress since 2017, and most recently held the position of vice chair of the House Republican Conference, he has little name recognition among average Americans.

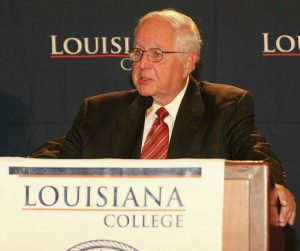

Paul Pressler addresses an audience at Louisiana College in Pineville, La. on Aug. 16, 2007.

Few would especially remember the role he played within the larger story of Southern Baptist higher education in recent years.

In August 2007, Louisiana College (now named Louisiana Christian University) announced plans to open a law school, the first in the state to be located outside the capital, Baton Rouge, or the largest city, New Orleans. The law school was named after Judge Paul Pressler, one of the principal architects of the “conservative resurgence” in the Southern Baptist Convention. Pressler was on hand for the announcement and asserted the need was great for a Christian-based law school.

A conservative transformation

Louisiana College, affiliated with the state Baptist convention, had undergone its own conservative transformation in the early 2000s once hardliners were able to set the direction of the board of trustees. The resignation of President Rory Lee in spring 2004 led to a controversial search process that culminated in the election of Joe Aguillard, chair of the school’s education department, in January 2005.

Joe Aguillard

Aguillard set out to remake LC as a bastion of ardent theological and political conservatism, cultivating overt connections to the Republican Party and right-wing causes. President George H.W. Bush was the keynote speaker for the school’s 100th anniversary in 2006. The 2009 commencement ceremony featured pseudo-historian David Barton, a prominent advocate for the discredited notion that the United States was founded as a Christian nation (and later a listed member of the law school’s National Board of Reference). In 2012, LC filed a lawsuit through the Alliance Defense Fund (now Alliance Defending Freedom) to oppose the Obamacare mandate for contraceptive coverage in health insurance.

Johnson served for some time as a senior legal counsel and spokesman for ADF — until, that is, September 2010 when he was named dean of the forthcoming Pressler School of Law. With his commitment to conservative legal and political stances and his history of litigation, he was a natural fit for the school. His record included defending Louisiana’s constitutional ban on same-sex marriages and, after his time with Louisiana College, state tax rebates granted to Answers in Genesis’ Ark Encounter theme park in Kentucky.

Commenting on the Obamacare mandate, Johnson declared, “This is, in our view, perhaps the most direct assault on religious liberty that we’ve seen in a long, long time.”

The law school was clearly instituted to be a training ground for Christian lawyers who would unite constitutional originalism with social conservatism and the defense of religious privilege. The website noted its curriculum would acknowledge “the Judeo-Christian foundations and moral traditions of the American legal system.” It “embrace(d) the ideals of the Western legal tradition, with its historical recognition that faith and reason are both integral in the search for truth in law, morality and justice.”

A dream never realized

But the Pressler School of Law never opened its doors.

Joe D. Waggoner Federal Building in Shreveport.

When Aguillard announced the school, an original opening date was set for 2009. However, it was not until 2010 that LC declared the law school would be located in Shreveport, and in 2011 the former Joe D. Waggoner Federal Building was purchased. Dilapidated and filled with asbestos, the facilities required extensive renovation and abatement, for which LC spent about $4.6 million over the next two years.

Meanwhile, Aguillard had been presenting a flurry of initiatives to expand the scale of education offered by Louisiana College, including a medical school, a film school, a divinity school and an undergraduate center in Tanzania. Almost none of these would see the light of day, as the Aguillard administration was defined by incompetent, authoritarian leadership and financial mismanagement.

In December 2011, the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools placed LC on warning status for significant non-compliance with multiple standards of accreditation. Additionally, in June 2012, SACS denied an ascent from Level III to Level V accreditation that would allow the proposed law school to confer degrees. In its report, SACS noted LC “did not provide an acceptable plan and supporting documentation to ensure that it has the capability to comply” with the standards of note.

Seeing the writing on the wall, Johnson resigned as dean in August. In his resignation letter to Aguillard, Johnson wrote that the SACS denial of an accreditation level increase negatively impacted fundraising and the recruitment of quality faculty and students, and that the college’s warning status meant approval likely would not be forthcoming. In the public announcement of Johnson’s departure, Aguillard gave a positive spin, emphasizing the job offer the former received from Liberty Institute, a Christian conservative legal organization focused on First Amendment issues.

Although Aguillard insisted Louisiana College would press on with developing the Pressler School of Law, the Waggoner building was placed on the real estate market in 2013 and eventually bought by the state for $1.75 million, nearly two-thirds less than the total LC had spent on purchase and repair.

Controversy increased at Louisiana College as whistleblowers sounded the alarm on misappropriation of funds. Aguillard responded with the claim that his presidency was under attack from Calvinists, but eventually the board forced him out of office in 2014.

Not on his bio

Johnson, understandably, does not call attention to the misbegotten venture that was the Pressler School of Law. His deanship receives no mention on his official bio. At the same time, Johnson has not kept his distance from what is now Louisiana Christian University, where Aguillard’s fusion of religious and political convictions remains alive and well under new management. Last November, Johnson spoke at the school’s seventh annual Values and Ethics Conference, where he gave an address replete with Christian nationalist talking points.

Johnson’s political career took off in 2014 with his election to the Louisiana House of Representatives and then to Congress two years later. The higher platform of federal office provides a more fruitful ground than a small, obscure Baptist college to advance his opposition to abortion and LGBTQ rights and his support for conservative interpretations of religious freedom. And now, as speaker of the House, he will lead Republican efforts to stymie the Biden administration.

During her nomination speech on behalf of Johnson, Rep. Elise Stefanik referred to him as a “friend to all and enemy to none.” By all accounts, he is well-liked by his GOP colleagues. But as a self-described fighter on the front lines of the culture war, Johnson is certain to be a lightning rod for controversy about Christian political engagement in the days to come.

Christopher Schelin

Christopher Schelin serves as dean of students at Starr King School for the Ministry in Oakland, Calif., and a senior research fellow at the International Baptist Theological Study Centre in Amsterdam, the Netherlands. He is a 2005 graduate of Louisiana College. Gratitude is extended to Rondall Reynoso and Vershal Hogan for their contributions to the preparation of this article.

Related articles:

Louisiana College to seek new president

Former president, now professor, reportedly on way out at Louisiana College

Accrediting agency lists reasons for putting Louisiana College on probation

Louisiana College changes name to boost academic reputation while hosting creationist conference