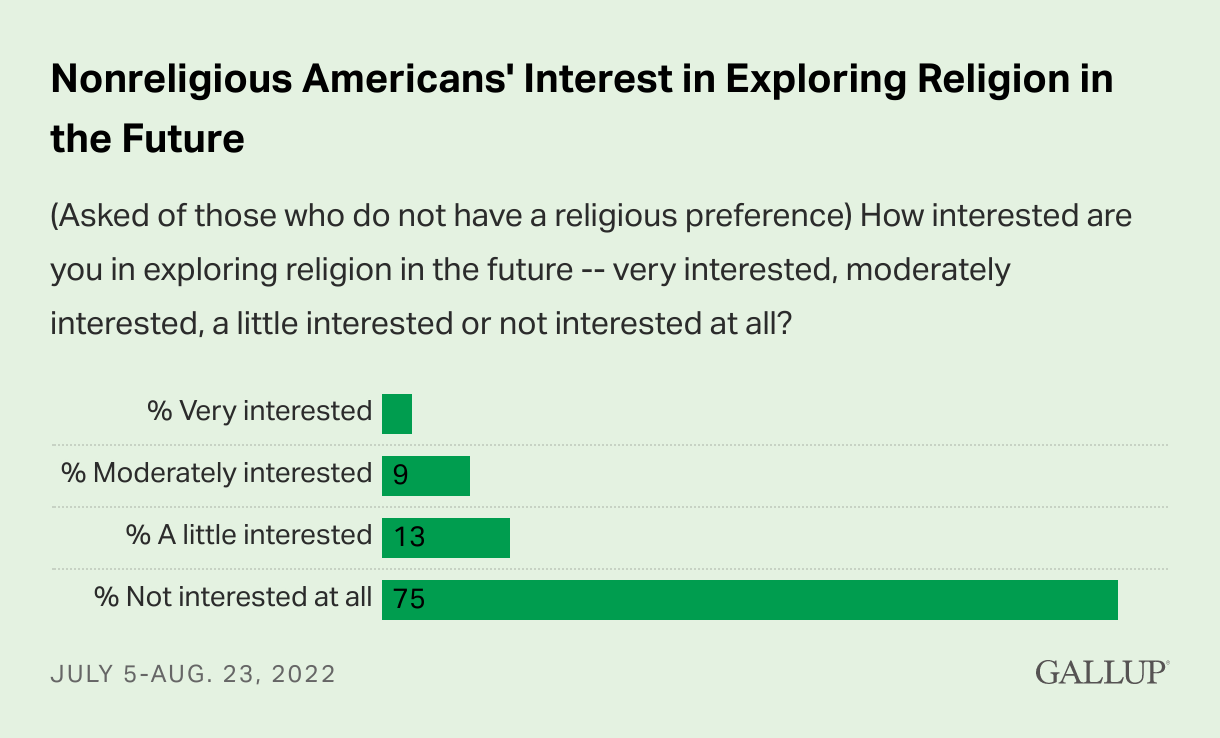

According to a recent Gallup Poll, 75% of U.S. adults who have no religious preference say they are “not interested at all” in exploring religion in the future. But broken down by age, young adults are more inclined than older adults to be interested in exploring religion.

Gallup’s survey found that the inclination to explore religion decreases with age.

For example, 18% of nonreligious 18- to 34-year-olds reported an interest in exploring religion in the future, compared to 9% of non-religious 35- to 54-year-olds and just 6% of non-religious adults 55 and older.

Additionally, nonreligious college graduates are less likely than non-religious adults without a college degree to want to explore religion. Of those religiously unaffiliated, only 4% of college graduates, compared with 17% of non-graduates, want to explore religion.

This does not mean, however, that education causes people to be less religious.

According to statistician and researcher Ryan Burge, educated people are more likely to be religiously affiliated and attend religious services than non-educated people. Despite popular belief, the relationship between college education and lack of religious curiosity is not causational.

However, it also is possible that college-educated people who are religious accept more secular beliefs and attitudes alongside their faith, possibly due to the diverse environment of college life, than non-college-educated religious people.

Gallup also found there is only a one-point difference in religious curiosity among nonreligious Americans who attended church services regularly or infrequently as children, with 13% of those who were regular churchgoers being interested, compared with 12% of infrequent churchgoers.

Gallup concluded these findings suggest two things.

Exposure to faith lessons early in life has little to no impact on unaffiliated American adults in their future religious orientation.

First, as people age, they are more “set in their ways” compared to younger people who may be more open to the possibility their worldview or life may change. Second, exposure to faith lessons early in life has little to no impact on unaffiliated American adults in their future religious orientation.

At first glance, Gallup’s survey offers a grim view of the future for churches in America. If only 18% of nonreligious young adults are interested in exploring religion, church attendance will continue to drop.

Listen to campus ministers

But before drawing such dreary conclusions, consider the experiences of two Baptist ministers, Caitie Walsh Jackson and Dane Jordan, who have spent ample time with college-age students as they explore what faith means to them.

Caitie Jackson

Jackson, campus minister for the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship of North Carolina, hosts a group called “Ask Me Anything” for students on the campuses of UNC Charlotte and Wingate University. The group is an effort to create a space for honest conversations and reflections about what faith means and where faith fits into the life of a college student.

Jordan, former campus minister and current director of parent-alumni relations at Wingate University, directed the Office of Campus Ministry for 20 years, working with students as they explored faith during their time on campus. As the campus minister, Jordan took on many roles for students as he guided them through the process of discerning the importance and meaning of their unique spiritual journeys.

Prior to changing positions at Wingate, Jordan worked with Jackson to facilitate the “Ask Me Anything” group. The two still collaborate to promote the group to students.

When asked what they think about Gallup’s findings, Jackson and Jordan had much to say.

“It doesn’t surprise me.” Jackson said. “When we’re younger, we have a broader sense of hope. When you’re older, you continue to have hope, but (young adults) are searching for what, well, ‘church people’ might say what ‘church gives,’ which is community and belonging, and a place to gather and connect.”

Young adults need community because it helps them “define themselves, to help build their villages and their people, and know where they belong. And represent what they believe in,” she explained.

“Young people are more open to the idea of having the faith part (of community) because what they’re looking for is connection and community.”

Jackson also talked about what she calls the “window of connection” young adults are in as they actively search for a community that can be found within religion. “Young people are more open to the idea of having the faith part (of community) because what they’re looking for is connection and community.”

She contrasted this with older adults, who may have missed out on finding a church or religious group, and instead found community elsewhere.

Consider the language

Jordan also was not surprised with the overall findings of the survey but wanted to know more about the “verbiage” of the questions asked.

“One of the things I have seen, and would even articulate in my own life, is wondering whether the words ‘religiosity’ and ‘spiritual’ were the same thing. I have, in my time, changed from being much more interested in the term ‘spirituality’ than ‘religious’ because I think we affiliate the term ‘religious’ with a particular construct of faith.”

He also wanted to know more about how the survey defined “frequent” and “infrequent” church attendance during childhood.

Dane Jordan

“I know very few kids who, in my time it was called ‘stayed for preaching.’ Sunday school was fine, let’s do that, but this guy’s up here and I don’t half understand. At what point did they cut that off? As children move into grade school, middle school and high school, those experiences do become important and would be something I think people would want to follow up with.”

In his experience, “As children, it could very well be that their experience and memory of how they felt (in church) was, you know, bored to tears and couldn’t wait to get done.” But he clarified that when he was a kid, “children’s church” was not around, and he thinks the institution of lessons created specifically for children in more recent years may have a different or more lasting impact on today’s youth.

‘A space to learn and grow’

Both Jackson and Jordan noted they have encountered people who were not religious, or religious but not Christian, yet curious and wanted to know more. When asked what those encounters were like, they shared stories about their ministries.

Jackson told two stories about students from her CBSF Charlotte ministry. The first student was a young man who came to Charlotte from New York, whose family was Muslim but not actively practicing the faith. “He was open about who he was, his history, about his faith and lack thereof, and that he was looking for a place where he could connect with other people.

“I told him about our denomination. I told him about what we do and what the environment is there, and I said, ‘Is this something you’re looking for?’ To be honest, I did assume it would not be.” But the student surprised Jackson when he said “Yes, I really just want a place where I can meet other people.”

He also told her, “I am really interested in just learning about it.”

“It had nothing to do with evangelizing him. It had to do with providing a space where he could also learn and question and grow.”

“He expressed multiple times that this became his family because it was a space he could just be in and not be the same, and not need to understand and believe the same, and learn and ask questions.”

Jackson explained: “It had nothing to do with evangelizing him. It had to do with providing a space where he could also learn and question and grow.”

‘Ask Me Anything’

Jackson also told about the creation of the “Ask Me Anything” series, which stemmed from a study on the book Shameless she did with a group of young women. “Throughout that time, they kept saying things like, ‘I didn’t know I could be in a church and talk about sex in a way that didn’t make me feel shameful.’”

She talked about the importance of a minister discussing these uncomfortable topics with students who were curious but nervous to ask.

“I do believe there is something powerful in transparency and understanding how to choose transparency,” she said. “I do believe you need somebody in a stole answering these questions honestly, saying, ‘I too have had these questions, I too have had these experiences, and I don’t want you to feel shame.’”

Influenced by Buddhist monks

Jordan reflected on his overall experience in ministering to nonreligious college students.

“In the 20 years I did that (ministering to Wingate students), it was very uncommon for unaffiliated members to have conversations with me about faith,” he said. “I wouldn’t say there was always this place where they were coming to seek me out, but if we happened to cross paths or I did a presentation and it was different than what they expected or had a preconceived notion, then they would come talk to me.”

He also shared a personal experience from his ministry to college students.

“There was a very poignant point in my time here when we had a group of Buddhist monks come, and while they would have definitely identified as religious, it wasn’t Christian.” Meeting them was a turning point in his own faith understanding. “I began to look at them and think, ‘They’re doing this way better than I am, so who’s more Christian?’ Then I started to have conversations with students, and one student, in particular, wanted to ‘witness’ to them. But I asked them, ‘What would change about their life if they converted to Christianity?’ If being Christian means to live your life like the Sermon on the Mount, they were already doing it.”

“If being Christian means to live your life like the Sermon on the Mount, they were already doing it.”

Overall, when asked what it was like to enter conversations with nonreligious, yet religiously curious people, he summarized: “It was very empowering for me. And the frustrating thing is that I didn’t always feel like I had the avenues available to re-engage those.”

He thought of himself as a religious authority who was different from others because he was not motivated to convert these nonreligious students to Christianity, he just wanted to have a conversation. He hopes that this experience was empowering for them too but admits he sometimes struggled to find the resources, support or most effective ways to continue ministering to this group.

The pursuit of knowledge

When asked what is unique about young people exploring religion in comparison to other demographics, Jackson and Jordan both discussed the pursuit of knowledge as a big factor.

“The majority (of young people) are asking questions and wanting to explore,” Jackson said, but adding this sometimes is a struggle. “To enter that space is vulnerable. It takes trust. It takes bravery.”

Young people, she said, “are still forming and shaping where they’re at. I remember my campus minister would lay out topics and let us ask anything. Have guided stuff, but let us ask anything, and he would say, ‘What do you think about this?’”

She always wanted to know what he thought about things, but her minister would push back. “He didn’t want to sway (our perspectives).”

She does this now in her ministry with college students.

“I want them to know there might be room to think differently.”

“I want them to know there might be room to think differently. I want them to know other people here at this table might be thinking differently, and it’s OK, and we can talk about it. It leaves a unique space to come in and meet them where they’re at and empower that. Not just, ‘What do you think?’ but, ‘Tell me more about what you are thinking.’”

She finds students “want to know it’s OK to be thinking about these things.” And college is a unique moment in time where there “isn’t an obligation to think one way or the other.”

Greater access to knowledge

Jordan believes younger people today are unique because they have greater access to knowledge than previous generations.

“Centuries ago, not everyone could read. Colleges were founded for two things — doctors and preachers — and in the town, those were the two highest-status people because they were the most educated. Whatever they said, you (as a congregation member) didn’t have any way of knowing whether that was right or wrong.

“Now, students have all this access to knowledge and diversity. Being a teenager in the ’80s, there was no way of experiencing what a Catholic worship service was like unless I went to a Catholic church, much less Muslim, Judaism or anything else. Now, you can Google and watch a whole service to understand that, just because the news and my preacher are telling me one thing about a particular religious group or ideology, I can go, ‘Well, let’s see what else people say about that’ and you can begin to see that there might be other opinions out there.”

Freedom to explore as a college student

Simply going to college makes a huge difference, the two ministers said.

“Right off the bat, students often freeze because there’s no one telling them what to believe, so it becomes their own action,” Jackson said. “It becomes their own responsibility so that immediately changes how they approach faith.”

“All these things you’re taught to keep at bay, you now have the opportunity to do, and that doesn’t always align with faith organizations.”

“All these things you’re taught to keep at bay, you now have the opportunity to do, and that doesn’t always align with faith organizations,” she said. There is a “consistent clashing” between how a person wants to live their life and what they think their faith is or should be.

She also spoke on the experiences of people who enter college without faith.

“They might experience people of faith and they’re totally turned off by it. They might experience people of faith and their eyes are open to it,” she said. “College directly has a huge impact on the way people connect with religion after their parents’ house.”

Jordan agreed the experience of learning and living in a diverse environment is particularly meaningful.

“College, because of who it exposes you to and what it exposes you to, can cause you to both question and affirm. And I personally believe that questioning is as important and valuable (to) my faith as the affirmation that what I do or did believe was or was not true.”

And having faith challenged also has value, Jordan said. “There is value in seeking out something that is not going to affirm your preconceived notions.”

Trust in the safe space

Even when a minister is open and has the best intentions, students may not trust that the space is truly safe to ask anything.

Jackson is intentional about “taking off the stole” before entering the “Ask Me Anything” conversation. The message she hopes to send is, “I am here to listen to you; I am not here to talk to you.”

Even so, students have a hard time learning how to trust each other.

“What we often talk about isn’t just a safe space. It requires being a brave space.”

“This thought of actually being in person, to actually verbalize personal things about your life, to trust the people around you — people might join it, but that jump is a huge leap to say, like, let’s trust these people here. What we often talk about isn’t just a safe space. It requires being a brave space. And I get that. I don’t ever push students to join it because of that.”

Jackson views campus ministry as a mixture of hospitality and mission.

But post-COVID, even a program like “Ask Me Anything” isn’t getting the participation it once did, Jordan said.

“I don’t know why this group doesn’t have as many people coming every week as other popular groups on campus. Is it marketing? Is it interest? I think there is a whole slew of students we are missing, and how do we create that space would be the No. 1 enigma for me,” he said.

Jordan believes the cancellation of in-person gatherings due to the pandemic may be causing students to have trouble re-integrating into the idea of participating in activities like this one.

And he suspects students might be apprehensive of the marketable “safe space” language.

“Students are savvy enough to know that, even the churches who say they’re open to everybody, yeah you can come, but if you’re not this, this and this, we’re going to expect you to change when you get here. It’s as if every church would say we’re open and welcoming of anybody. But it almost needs to be, ‘And we don’t expect you to change.’ I definitely think students are savvy enough to even question the marketing.”

Truly safe spaces

Circling back to the Gallup data, Jackson and Jordan considered what it might be like if the church was able to offer a truly safe space for people of all ages. Would it only be effective for young people, or would older generations respond as well?

“People are looking for connection. They’re looking for spaces to be community. But I don’t know what that looks like when it comes to being in the church because we’re not that vulnerable in the church,” Jackson said.

“Oh yeah. This is not the best analogy, but everybody’s got the itch that they want scratched,” Jordan added. “We all have an innate sense of faith. We’ve just got to figure out how to interpret it correctly for each person.”

While the polling data may look grim, it does not have to be interpreted that way, both Jackson and Jordan concluded. There is hope for the future of the church, and those involved in ministry can demonstrate that firsthand.

But it takes a great deal of work, a dedication to building relationships and a willingness to ask (or be asked) anything about your faith.

Related articles:

Most young people are unsettled in the new year but few plan to turn to the church for help

Online religion content isn’t luring Millennials away from in-person church