When you look at the dates on the hymn tunes and text in any hymn book, you quickly see many are 100 to 200 years old. Isaac Watts wrote “When I Survey the Wondrous Cross” in 1707, more than 300 years ago.

Entire modern industry has sprung up around Christian music and well-coifed, blonde women and handsome men with three-day beards grace CD covers to compete for sales on the same shelves as secular stars.

Deb Loftis, retired executive director of the Hymn Society in the United States and Canada, says she’s not qualified to talk about the “huge field” of church music in general, but in terms of congregational singing, she notes several trends.

Deborah Loftis, retired executive director of the Hymn Society in the United States and Canada

“Modern hymn writers tend to incorporate entire biblical stories, not just references to places in scripture,” she says. “If there is a formula, it would be that the Bible story is told in the first part of the hymn, and the rest of the hymn turns to reflection on what that means today, so it’s a little sermon right there in the hymn.”

She cites preacher/hymn writers Thomas Troeger and Carl Daw Jr. as two who do that well. In the first verse of “Silence, Frenzied, Unclean Spirit” by Troeger and Carol Doran, Jesus casts out demons in the first verse. The second verse addresses God, saying those demons still thrive in the gray cells of our mind and in the third verse, we plea for healing in our day.

“We Have Come at Christ’s Own Bidding” by Daw is a hymn on the transfiguration, and “The Hands That First Held Mary’s Child” by Troeger tells about Joseph the carpenter as newborn Jesus’ earthly father. It reminds us that we “hold” the baby at Christmas to remember that his path leads to the cross.

Modern congregational singing embraces a wide variety of musical genres. It’s no longer “a set of words in four or five stanzas to a tune in four-part harmony that repeats exactly for every stanza.”

Loftis says there is an increase in hymns dealing with topics of concern for current believers, songs of true lament that express grief and loss but don’t always move to a hopeful resolution at the end.

Modern hymns address divorce, domestic or community violence, justice and reconciliation, peacemaking and the dignity of all persons. Some are interfaith.

“Our concept of a congregational song is much broader now,” she explains. “There are songs that use a different melody structure, with more harmonic variety than you can incorporate in strict four-part writing. There are jazz idioms and more color chords apart from a standard harmony.”

Instead of a four-stanza hymn, congregations are using shorter forms, Taizé Community chants and short choruses from the Iona community. “While there are many repetitions, these songs are not repetitious,” says Loftis. There is variety in the chants with slight word changes and in the number of instruments used.

Baptists are “a little behind other denominations in psalms singing,” she adds, but more churches are singing the scripture. There are chanting, guitars, a cantor, and choir – “every variety you can imagine.”

Other congregations utilize folk, jazz, hip-hop and R&B styles in congregational singing as a “very important way to relate to their community.” And she notes the continuing contemporary Christian song genre, which is “becoming more sophisticated and less shallow.”

Reflecting a growing awareness of the universal Church, congregations are incorporating music and song styles from across the globe, even singing in non-native languages.

Glory to God, a newer Presbyterian hymnal, features a number of songs in other languages, with English included.

Adult Choirs at Risk

The iconic image of congregational singing in Baptist churches is the adult choir. Sometimes the choir is led by a formally educated or professional musician, but more often by a volunteer or music director with little training in congregational music.

Ken Wilson, now retired after 32 years as minister of music at Knollwood Baptist Church in Winston-Salem, N.C., conducts a rehearsal.

Ken Wilson, who retired in March 2018 after 32 years as minister of music at Knollwood Baptist Church in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, says a fact of current church music life is that fewer people are willing and able to commit the time to practice every Wednesday night and to sing every Sunday.

That was the model for most of his ministry – and for centuries in the Church. Wilson believes at least some forms of that model “will survive but will be tough to sustain. The experience for choir members has to be rich, invigorating and fresh.”

Another challenge for many churches is that budget hawks will question the need to buy new sheet music at $2.50 per copy. “You have drawers full of music; why do you need new music?”

Buying 60 copies of anthems and other choral music for each of 52 Sundays would be prohibitive, but choirs need fresh, new songs to stay vibrant. To save money, Wilson found some churches with which to exchange music and kept the annual budget for new music to $2,000.

Training future church musicians

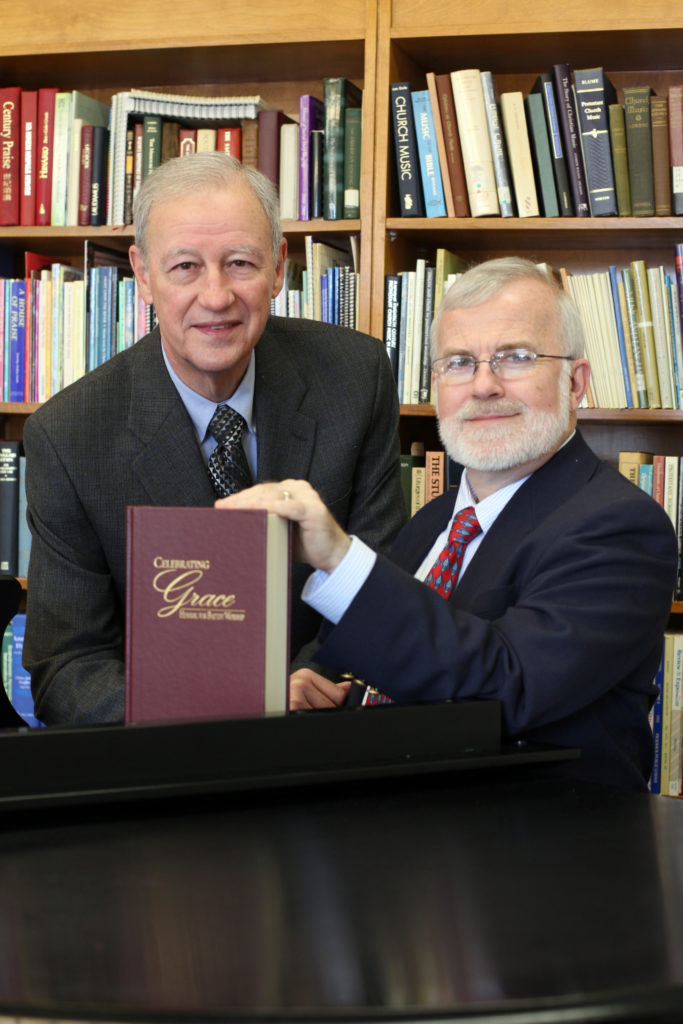

Paul Richardson taught church music at Southern Seminary – even while he was director of admissions – until 1993 when he found a happier home at Samford University after trustees led the seminary in a different direction as part of the fundamentalist takeover of the Southern Baptist Convention. The founding documents of Samford include the purposes of (1) To train ministers of the gospel, and (2) To train leaders for the church in music.

He’s not encountered similar founding purposes for music in other educational institutions.

Paul Richardson, with Milburn Price, retired dean of the school of music at Samford University

Music schools are costly, Richardson says. “You have to have specialized faculty, facilities, library resources. It’s an expensive thing to do, no matter what kind of institution it is or how broad its vision.”

Even in 1942 when Ellis Fuller became president of Southern Seminary, coming from the pastorate of First Baptist Church, Atlanta, faculty protested the potential loss of resources when he started a music education program, following the models of sister seminaries New Orleans and Southwestern.

Fuller’s successor, Duke McCall, had to deal with the “bickering and infighting” still present, so he asked trustees to abolish the music program. It wasn’t what he wanted, but he forced the trustees to own the decision. When they rejected his request, Richardson says, McCall affirmed their decision and made music education “an integral part of the curriculum.”

Southwestern and New Orleans seminaries have also retained their church music programs. Other schools have tried to start music programs but found them unsustainable financially, Richardson says. Even at Samford, he never had more than 12 graduate students in church music at one time.

Recognizing that they had lots of students who already were leading worship in local churches but had no vocational aspirations in church music, Samford developed a minor in worship leadership.

“We’re essentially back to 1950,” Richardson explains. “We have musicians in church, most of whom are university educated. They are good musicians, committed to the church, they love Jesus, but nobody’s getting specialized training in church music.”

He recognizes that “nobody” is hyperbole, but there are tens of thousands of Baptist churches, and certainly music and congregational singing in the majority of them are not being led by persons trained in church music.

In his case, Richardson is committed enough to the idea of special training in church music that he thinks a church musician should have a master of divinity degree, the traditional degree of a pastor.

“I think nearly all groups of Christians have sung their faith,” he says. Like everything else, culture shapes style and content and “every few years it seems – especially progressives – feel like they are discovering a new thing, only to find out they were practices of people hundreds of years ago. We ignore the communion of saints at our peril.”

With a chuckle in his voice, Richardson says hymns are ecumenical, and if you asked most Baptists to sing a good old Baptist hymn, “they would probably pick one by Fanny Crosby, who was a Methodist.”

Read more in the Hymns for a Lifetime Series

Hymns for a Lifetime: Poetry added to music makes not only hymns, but memories

Photo Gallery: Hymns for a Lifetime

Related commentary at baptistnews.com:

Making God smile through music | Doyle Sager

Too busy to sing? Try anyway | Brett Younger

Related news at baptistnews.com:

Songwriter sees ‘good news’ in declining role of church music

Brian McLaren: It’s time to re-write pro-war hymns

Hymns for a Lifetime is a series about retired music minister Ken Wilson from Knollwood Baptist Church, Winston-Salem, N.C. and the process he used to make sure children and youth are taught to sing hymnic heritage, led to sing these hymns regularly and to enjoy singing these hymns. This series in the “Singing Our Faith” project is part of the BNG Storytelling Projects Initiative. Music is integral to our faith but some individuals and congregations take this expression of ourselves to a new level. In “Singing Our Faith,” we explore this relationship between music and faith and the creative ministers, church leaders and congregations leading the way.

_____________

Seed money to launch our Storytelling Projects initiative and our initial series of projects has been provided through generous grants from the Christ Is Our Salvation Foundation and the Eula Mae and John Baugh Foundation. For information about underwriting opportunities for Storytelling Projects, contact David Wilkinson, BNG’s executive director and publisher, at [email protected] or 336.865.2688.