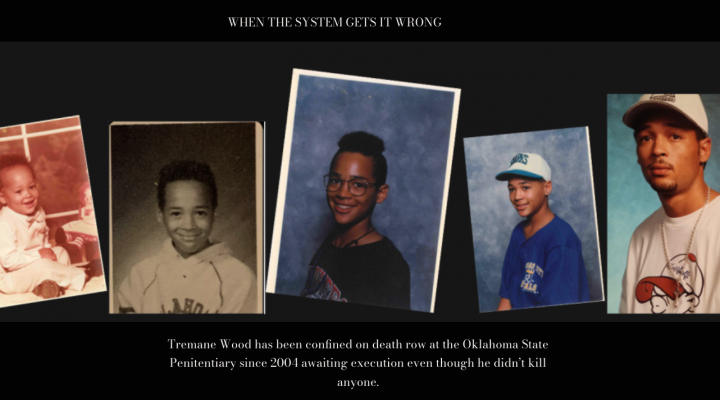

Death penalty opponents are bracing for the anticipated execution of an Oklahoma man who even the state acknowledges did not kill anyone.

Tremane Wood has been on Oklahoma’s Death Row since 2004 for participating in a robbery-turned-homicide in which the actual killer received a life sentence.

Yet Wood ended up on Death Row “after being convicted of what’s called ‘felony murder’ for participating in a robbery during which his older brother unexpectedly and tragically killed someone,” assistant federal public defender Amanda Bass said during an April 24 webinar hosted by Equal Justice USA. “Under Oklahoma’s felony murder rule, the state could and did seek the death penalty against Tremane without ever having to prove that he killed anyone or that he intended to kill him.”

The American Civil Liberties Union describes felony murder as a legal doctrine in use nationwide allowing authorities to charge defendants with first- or second-degree homicide when death results from the commission of a felony.

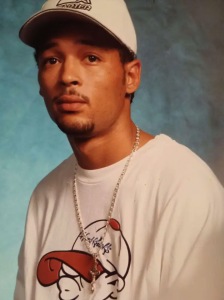

Tremane Wood

In Oklahoma, the law “removes the state’s obligation to prove the ‘intent to kill’ requirement while subjecting the defendant to the same level of punishment. According to state statute, when an individual is convicted, pleads guilty or pleads nolo contendre (does not contest charges), the punishment is either life with or without the possibility of parole or the death penalty,” the ACLU explained.

Bass, who is part of the legal team representing Wood, said her client is the only inmate on Oklahoma’s Death Row for a felony murder conviction.

“It is innately unjust and it reflects a kind of policy judgment that state legislatures make about wanting to penalize people through this extreme sanction,” Bass said. “It’s a law that is still on the books in Oklahoma and, as a result, you can have people like Tremane who are facing execution even though the actual killer has gotten a lesser sentence.”

Bass was invited to participate in the webinar to highlight the disparities inherent in the death penalty and in the nation’s wider criminal legal system, said Sam Heath, event moderator and leader of EJUSA’s evangelical network.

The criminal legal structure is based on fear and a thirst for revenge that disproportionately targets the poor and people of color, Heath said. Other than the desire to see people punished, most arguments for capital punishment aren’t getting much traction even from many supporters.

“We know that the death penalty is wildly expensive. We know that the death penalty does not deter crime. We know that it’s applied in an arbitrary manner. We know that it’s done in a torturous manner, and we know that it is not a path of healing for murder victims’ families and their recovery from what’s happened to them,” he asserted.

Wood’s case highlights the economic disparities that influence the prosecution and sentencing phases in capital cases, Heath said.

Amanda Bass

The deck was stacked against her then 22-year-old client when a judge decided he and his brother, both charged with murder, would be tried separately, Bass explained. As a result, Wood was assigned a solo practitioner from a list of death-qualified lawyers, while his brother, who admitted to the killing, was defended by a legal group with multiple attorneys and investigators with death penalty experience.

Wood’s attorney “put up no defense for him and admitted later that he didn’t do much at all to represent Tremane or to investigate his case,” Bass said. “We have an invoice from this lawyer showing that over the nearly two years that he was assigned to represent Tremane before trial, he worked only 80 hours on Tremane’s case, and 60 of those hours were just showing up for the trial.”

As a result, the jury did not learn that Wood’s brother had confessed, that he had been heavily pressured by his brother to participate in the robbery or that Wood nevertheless experienced significant remorse for the killing, Bass said. “When you compare that to the zealous representation his brother had from three experienced capital defense lawyers, two investigators who scoured the earth for information relevant to his defense, you can see the difference in sentencing outcomes.”

Bass said she and her team are trying to convince the trial and appellate courts in Wood’s case to consider evidence not presented at trial or subsequently uncovered.

Meanwhile, attorneys are preparing a case to seek clemency once an execution date is set.

“We have to get people to care about his case and to make him an individual and to humanize him to Oklahoma decision makers.”

And there is a way for individuals and churches to help, Bass said. “One of the things you can do is go to Tremane’s website and sign the petition for clemency. We have to get people to care about his case and to make him an individual and to humanize him to Oklahoma decision makers so that he’s not just a number in line to be executed.”

Heath added that some Oklahoma leaders are growing weary of the state’s capital punishment system and its many flaws.

One evidence of the problem is a bipartisan commission’s 2017 report recommending extension of a five-year execution moratorium that expired in 2020. While the recommendations were rejected, the effort shows doubts exist about the way Oklahoma executes inmates.

Also noteworthy is the state’s decision to scale back a plan to execute 25 prisoners between August 2022 and December 2024. Instead of executing 11 inmates last year, for example, it executed four.

And legislation was introduced this year to remove the death sentence as an option for those charged with felony murder, Heath said. “That bill did not make it out of the committee, but I think it reflects a growing level of understanding and interest.”

Related articles:

Faith leaders call for urgent opposition to Oklahoma plan to execute an inmate a month for two years

Opposition to death penalty gaining steam through broad coalition