When my two favorite singer-songwriters both released albums within a single week, I was reminded of the prophet Joel’s promise that “your old men will dream dreams.”

Paul Simon will be 82 in October, and Bruce Cockburn just turned 78, so they definitely qualify as old men. And Simon’s Seven Psalms and Cockburn’s O Sun O Moon both were inspired by actual dreams dripping with hope and glory.

But when it comes to God and what lies on the far side of death, these prophet-poets freely admit they don’t have much empirical data to offer. They are speaking far more than they can prove, more than they know.

But when it comes to God and what lies on the far side of death, these prophet-poets freely admit they don’t have much empirical data to offer. They are speaking far more than they can prove, more than they know.

This tension between faith and doubt reminded me of Walter Brueggemann’s thesis in Finally Comes the Poet: Daring Speech for Proclamation. Brueggemann argued that preachers are tempted “to quiet the text, to silence this deposit of dangerous speech, to halt this outrageous practice of speaking alternative possibility.” We come in search of certitude, he said, “but the poetic speech does not give certitude.”

Prophets like Joel had to be shocked by the audacity of their own words. They were hoping God would be shocked too. Shocked enough to respond, even if the road to redemption led through “the great and terrible day of the Lord.”

The inspiration for Brueggemann’s seminal book was a Walt Whitman poem, “A Passage to India,” written to commemorate the building of the Suez Canal in 1867. Like everyone else, the poet was impressed with the “proud truths of the world” and the “facts of modern science” on display in that massive engineering project. But his heart was drawn to something science could not provide.

The far-darting beams of the spirit, the unloos’d dreams,

The deep diving bibles and legends,

The daring plots of the poets, the elder religions;

O you temples fairer than lilies, pour’d over by the rising sun!

O you fables, spurning the known, eluding the hold of the known, mounting to heaven!

Paul Simon or Bruce Cockburn have been “eluding the hold of the known” since I was a kid. And I have followed them every step of the way.

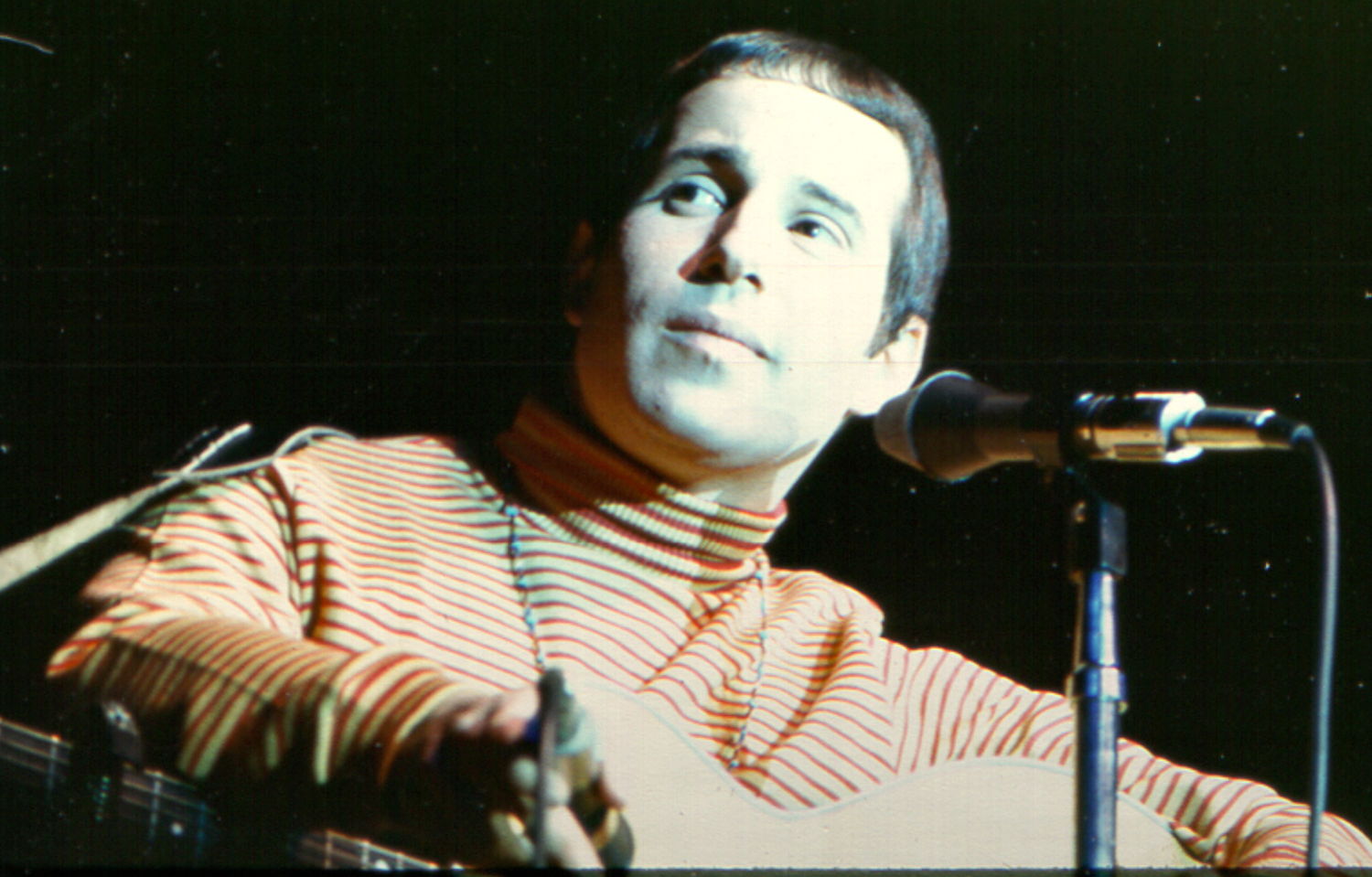

Paul Simon, around 1960. (Photo by Paul Ryan/Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images)

Introduction to Paul Simon

I still remember singing the lyrics to Simon’s first hit as I tossed newspapers:

Hello darkness, my old friend

I’ve come to talk with you again

Because a vision softly creeping

Left its seeds while I was sleeping

And the vision that was planted in my brain

Still remains

Within the sound of silence.

Soon, I had my own guitar and was busily working out the chords and lyrics to Simon’s “The Boxer”:

Asking only workman’s wages, I come looking for a job

But I get no offers

Just a come-on from the whores on 7th Avenue

I do declare, there were times when I was so lonesome

I took some comfort there.

My father took a dim view of these lyrics and told me so; but, for me, Simon’s musical narrative was far more stimulating than the safe, staid hymn lyrics we sang on Sunday mornings. I resonated with a line from “My Little Town”: “It’s not that the colors aren’t there, it’s only imagination they lack.”

“For me, Simon’s musical narrative was far more stimulating than the safe, staid hymn lyrics we sang on Sunday mornings.”

Paul Simon’s religion

Born in 1941, Simon came of age in the Jewish community of Queens. But shortly after becoming bar mitzvah, he turned his back on formal religion. His work always has been replete with religious references, but most are either gently mocking (“Jesus loves you more than you will know/Heaven holds a place for those who pray,” in “Mrs. Robinson”), or borrowed from the Gospel genre (“Like a bridge over troubled water I will lay me down”).

One striking exception is the little-noticed “Silent Eyes” from his 1974 album Still Crazy After All These Years.

Silent eyes watching

Jerusalem make her bed of stones.

Silent eyes,

no one will comfort her,

Jerusalem weeps alone.

All this suffering and no power, human or divine, can stop it. Still, Simon is adamant that justice will ultimately be served:

We shall all be called as witnesses

Each and every one

To stand before the eyes of God

And speak what was done.

Simon always has denied having settled religious convictions. Does that disqualify him as a prophet? Or might religious convictions that are too firmly settled silence the prophetic call Walt Whitman had in mind?

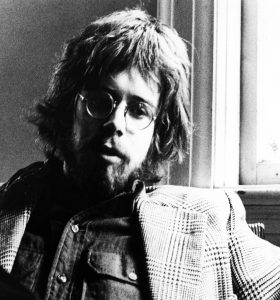

Bruce Cockburn, date unknown. (Photo by Gems/Redferns)

Discovering Bruce Cockburn

During my university years, I conferred the prophetic mantle on a second artist, Bruce Cockburn. Virtually unknown in America in the early 1970s, Cockburn already had attained iconic status in my native Canada. A celebrated guitarist, he combined lyrical brilliance with musical elegance. Even better (to my evangelical ears, anyway) Cockburn was a born-again Christian, as evidenced in “All the Diamonds”:

I ran aground in a harbor town,

Lost the taste for being free.

Thank God he sent some gull-chased ship

to carry me to sea.

Born in 1945, Cockburn grew up in Ottawa, Canada. His agnostic parents sent him to Sunday school because, in the early 1950s, that’s what you did. Like Simon, Cockburn ditched organized religion at the earliest opportunity, flirting with everything from Buddhism to black magic as an adolescent.

“His conversion to Christianity was the direct result of a mystical encounter during his wedding service in 1969.”

His conversion to Christianity was the direct result of a mystical encounter during his wedding service in 1969 when he realized a spiritual presence was standing next to him at the altar. Since they were in a church, Cockburn associated this unseen presence with Jesus.

During the late 1970s, Cockburn struggled to find a place within evangelical Christianity. He was drawn to C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, Thomas Merton and, a bit later on, Harvey Cox. Moving to Toronto in 1980, Cockburn couldn’t find a church that felt much like home. He was increasingly put off by the growing cross-fertilization between popular Christianity and conservative politics.

Throughout the 1980s, Cockburn toured with a full band, pushing his acoustic folk repertoire onto the back burner. Frequent visits to warzones in places like Nicaragua and Mozambique opened his eyes to a world of suffering beyond his worst imaginings. A political edge laced with undisguised anger crept into his music.

Bruce Cockburn at KBCO Studio C in Boulder, Colo.. (Photo by Tim Jackson/WireImage)

Life changes

A visit to a Guatemalan refugee camp in Southern Mexico changed his life forever. The American-funded military of Efraín Ríos Montt (an evangelical Christian) strafed the camp on a daily basis. Death and disfigurement were rife. Cockburn didn’t hold back.

I don’t believe in guarded borders and I don’t believe in hate.

I don’t believe in generals or their stinking torture states.

And when I talk with the survivors of things too sickening to relate

If I had a rocket launcher I would retaliate.

When “If I Had a Rocket Launcher” was released in 1984, Cockburn attracted enough attention to begin touring south of the Canadian border. Some of his old evangelical supporters fell away, partially because Cockburn’s religious references had grown more subtle and indirect over time. For decades, put off by the harder-edged music and the angry tone of his lyrics, I stopped buying Cockburn’s albums, but I still listened to the old stuff all the time.

By 2011, Cockburn moved to San Francisco with his wife, M.J. Hannett, an attorney working with the U.S. Department of Homeland Security. In 2014, grieving a tragic death, Hannett found her way to the San Francisco’s Lighthouse Church. Insisting that his churchgoing days were over, Cockburn was reluctant to accompany her. She was insistent.

Cockburn was overwhelmed by what he found at Lighthouse. The congregation was relatively small, racially and ethnically diverse and nondenominational. The church skewed young, and everyone seemed thrilled to be there. They danced as they sang. They were Black and white, gay and straight.

“No one had a clue who Bruce Cockburn was and, when the worship team needed a guitarist, they asked if he played.”

No one had a clue who Bruce Cockburn was and, when the worship team needed a guitarist, they asked if he played. Lighthouse had a big impact on Cockburn’s Bone on Bone album (2017). Listening to a sermon on Israel’s 40-year trek through the wilderness of Sinai, Cockburn realized it had been that long since he had experienced real Christian community. The sermon inspired a song:

Forty years of days and nights — angels hovering near

kept me moving forward though the way was far from clear

and they said

take up your load

run south to the road

turn to the setting sun

sun going down

got to cover some ground

before everything comes undone

Five songs on O Sun O Moon were written while Cockburn vacationed in Maui with the church’s pastor during the COVID-19 pandemic. The title tune, “O Sun by Day, O Moon by Night,” was inspired by a death dream in which, following a long, wearying journey, he approached an angel guarding huge gates of bronze. When Cockburn requested permission to enter, the angel stepped aside and the gates swung open. But his journey was not over. Inside the gate, the road continued. And so, as the melody ascends with each new line, Cockburn sings:

O sun by day, o moon by night

Light my way so I get this right

And if that sun and moon don’t shine

Heaven guide these feet of mine

To glory.

The album concludes with “When You Arrive,” song in which the veil separating the living from the dead begins to blur:

And the dead shall sing

To the living and the semi-alive

Bells will ring

When you arrive.

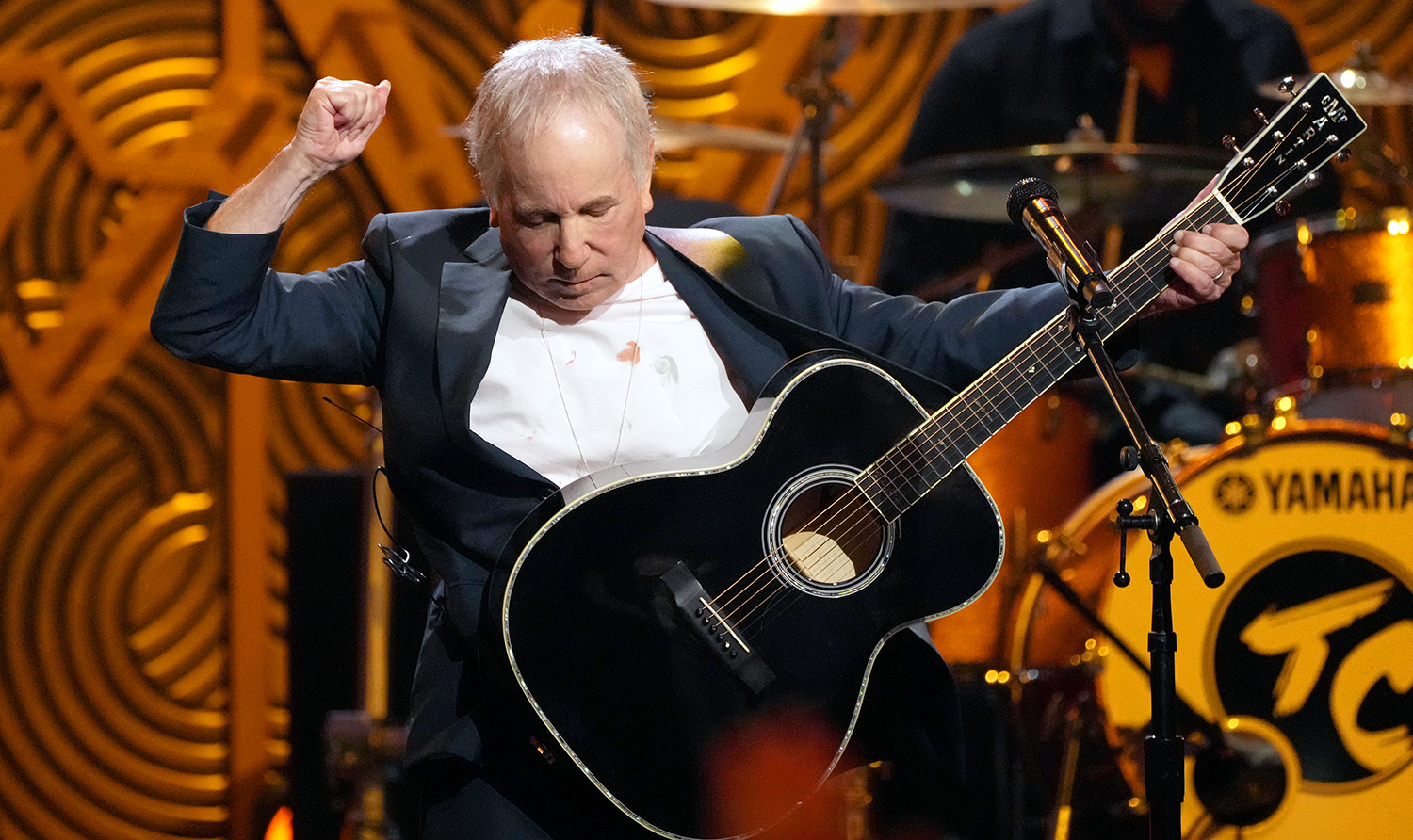

Paul Simon performs onstage during Homeward Bound: A GRAMMY Salute To The Songs Of Paul Simon at Hollywood Pantages Theatre on April 6, 2022, in Hollywood, California. (Photo by Kevin Mazur/Getty Images for The Recording Academy)

Paul Simon’s vision

On Jan. 15, 2019, Paul Simon was informed in a vivid dream that he was writing a work called Seven Psalms. It wasn’t that he was supposed to write it; he already was writing it. Soon, he was waking up between 3:30 and 5 a.m. with words and phrases coursing through his head. If he waited until morning to write them down, they were irrecoverable. They could only be recorded the second they arrived.

“If I used my experience as a songwriter, it didn’t work,” Simon recently told an interviewer. “And I just went back into this passive state where I said, ‘Well, it’s just one of those things where it’s flowing through me and I’m just taking dictation.’ That’s happened to me in the past, but not to this degree.”

Simon conceives Seven Psalms as a unity, which is why the album has only one 33-minute track. There are seven psalms, to be sure, but the piece is held together by a refrain Simon simply calls “The Lord”:

The Lord is the earth I ride on

The Lord is the face in the atmosphere

The path I slip and slide on.

Or,

The Lord is a virgin forest

The Lord is a forest ranger

The Lord is a meal for the poorest

A welcome door to the stranger.

But just when we think Simon is getting sentimental, he sings:

The COVID virus is the Lord

The Lord is the ocean rising

The Lord is a terrible swift sword

A simple truth surviving.

Bruce Cockburn present day publicity photo

Prophetic imaginations

Both Seven Psalms and O Sun O Moon celebrate the interwovenness of creation. Simon tells us that “love is like a braid.” Cockburn tells us that “we’re but threads upon the loom when the spirit walks in the room.”

Both albums are almost entirely acoustic, with Simon and Cockburn proving their guitar chops are undiminished by age. Both men sound like octogenarians yet are in excellent voice.

“While Simon is a pendulum swinging between faith and doubt, Cockburn sings like a convinced person of faith.”

But there is one major difference. While Simon is a pendulum swinging between faith and doubt, Cockburn sings like a convinced person of faith.

And yet, asked pointblank what waits on the other side of death, Cockburn is just as noncommittal as Simon.

“I don’t really know what’s going to happen,” Cockburn recently admitted. “My own belief is that I will be at least faced with an opportunity to get closer to God. … At the very least, the energy that is contained in your body is going to go out to the universe and you do literally become part of everything.”

“I don’t really know what’s going to happen,” Cockburn recently admitted. “My own belief is that I will be at least faced with an opportunity to get closer to God. … At the very least, the energy that is contained in your body is going to go out to the universe and you do literally become part of everything.”

Just as Simon and Cockburn were finding their poetic bearings in the mid-1960s, Catholic theologian Karl Rahner predicted: “The Christian of the future will be a mystic or he will not exist at all.”

Simon and Cockburn may be the kind of mystics Rahner envisioned.

“I feel a sense of standing on the edge of the precipice when I think about death,” Cockburn recently observed. “But I also know there’s love out there, and it’s huge. And that love flows everywhere, including through me.”

Simon’s reluctance to explain his encounters with the transcendent is a measure of how seriously he takes these things. But he knows what it means to be caught up in a “huge love … that flows everywhere.”

In one of the Seven Psalms, “The Sacred Harp,” Simon prays the Spirit that courses through the Bible might be alive in our world:

The sacred harp

that David played to make his

songs of praise

we long to hear those strings

that set his heart ablaze.

Paul Simon and Bruce Cockburn are old men dreaming dreams. Consciously, and unapologetically, they are spinning “fables spurning the known, eluding the hold of the known, mounting to heaven.”

That might not be the kind of prophet we are looking for; but it might be exactly what Joel had in mind. Thanks be to God.

Alan Bean

Alan Bean serves as executive director of Friends of Justice. He is a member of Broadway Baptist Church in Fort Worth, Texas.