I don’t like being told what to do, think or say. You got a problem with that?

I know that sounds excessively pugnacious and not very Christian, considering the ugly divisions and hatreds roiling Americans in recent years. But I stand by it.

Part of my reflexive resistance comes from basic orneriness and problems with authority. I didn’t want to lie down for afternoon naps on my little towel in kindergarten. I didn’t always play well with others. I climbed out of the classroom window in ninth grade. School suspensions weren’t punishments to me; they were mini-vacations. I wasn’t much of a joiner. I didn’t obey the rules.

Erich Bridges

If it’s popular, I don’t like it. If it’s accepted, I question it. If it’s trendy, I reject it.

Not that I’m a courageous rebel, mind you. I’ve cravenly submitted to authority plenty of times over the years when faced with the threat of losing jobs, comforts and other advantages. I’ve also had some patient, long-suffering bosses, pastors and friends.

Gotta serve somebody

Even when you’re bullheaded, eventually you’ve “gotta serve somebody,” as Bob Dylan, the most stubbornly independent artist of our age, admitted in his classic song of the same name. “It may be the devil or it may be the Lord, but you’re gonna have to serve somebody.”

Submission, when it isn’t forced, is the ultimate proof of belief and commitment. “If you love me, you will obey me,” Jesus said in John 14:15, echoing the great commandment of God in Deuteronomy 6:4-5.

So believe God. Love God. Obey God. But question everybody else. That’s my policy.

“Believe God. Love God. Obey God. But question everybody else. That’s my policy.”

That’s why I’m Baptist. Three of the joys (and grave responsibilities) of being Baptist are freedom of conscience, the priesthood of the individual believer and “soul liberty.” Yes, we have an ultimate authority: the word of God and the divine author who inspired it. Parents, preachers, pastors and teachers may help us interpret it, but in the end each of us decides in the sanctuary of our own hearts what it means and what it calls us to do.

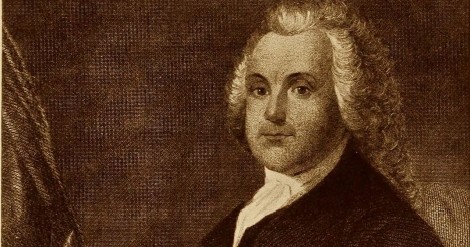

Roger Williams, father of us all

Let us now praise Roger Williams (1603-1683), founder of the first Baptist church in America and of the colony that became Rhode Island. The colony was a haven of freedom — both for believers of all kinds and nonbelievers — from the tyranny of the Puritans, who banished Williams, a rebel Puritan minister, from Massachusetts for advocating religious tolerance, church-state separation and liberty of conscience.

“Forcing of conscience is a soul-rape,” Willams declared. And: “Man hath no power to make laws to bind conscience.” And again: “God needeth not the help of a material sword of steel to assist the sword of the Spirit in the affairs of conscience.”

He stood for strict separation of church and state, but his revolutionary ideas about individual freedom eventually became a blessing to all — in America and beyond.

“We must look to Roger Williams, more than to (Thomas) Jefferson or (James) Madison, as the true builder of our American Bill of Rights,” wrote Charles Small Longacre in 1939, “because all the provisions of civil and religious liberty as set forth in the matchless Constitution of the United States were incorporated in principle in the charter of Rhode Island as conceived and framed by Roger Williams. … The great apostle of soul liberty was the instrument that gave inspiration and guidance to the shaping of the fundamental law of a nation which was destined to become the champion of the rights of all men.”

“Take that, rabid secularists and theocrats. A passionate preacher of the gospel put a pox on both your houses in the name of freedom.”

Take that, rabid secularists and theocrats. A passionate preacher of the gospel put a pox on both your houses in the name of freedom, and we might have no real democracy today without him.

Silencing others

But we’re unwittingly rejecting Williams nearly as often these days as the Puritans did when they ran him out of Massachusetts.

Freedom of conscience — and its close companion, freedom of speech — are under attack yet again, as they have been almost continuously since they were enshrined in the Constitution. The assailants are the usual suspects: the state, political and religious demagogues, cultural commissars, self-appointed censors.

“The compulsion to silence others is as old as the urge to speak,” observes Eric Berkowitz in Dangerous Ideas, a new history of censorship.

Often the censors are easily identifiable: Political authoritarians always seek to silence dissent and crush a free press, which they fear as threats to their power. Religious authoritarians seek to stamp out any resistance to their definitions of truth.

We’ve seen both types on full display in recent years.

Populist-nationalist bullies — from Donald Trump in America to Narendra Modi in India and Xi Jinping in China — establish xenophobic personality cults and attack anyone who resists their lies and distortions.

In the religious realm, we’ve witnessed the ongoing manipulation of evangelical believers by politicized preachers and authoritarian “leaders,” who rule by fear and try to muzzle or intimidate their critics. Case in point: The relentless attacks on Bible teacher Beth Moore and ethicist Russell Moore by the fundamentalist good-ol’-boy network that still controls the shrinking Southern Baptist Convention.

Conversations, not harangues

Sometimes, however, threats to freedom of conscience and speech come from people with good intentions. We’ve recently entered into much-needed “national conversations” and “reckonings” about racism, sexism, inequality and other national sins. These conversations are painful, but they’re long overdue and crucial to our humanity, faith and culture.

“Conversations need to be conversations — not one-way harangues by the ‘woke’ aimed at re-educating the clueless masses by any means necessary.”

But conversations need to be conversations — not one-way harangues by the “woke” aimed at re-educating the clueless masses by any means necessary. If people are afraid to speak because they might give offense or get “cancelled,” they will remain silent, either in fear or seething resentment.

The Left, perhaps even more than the Right, loves to shame, censor and intimidate opposing voices. Rigid groupthink rules academia’s “safe spaces” and wide swaths of popular culture. If you contradict it, you risk a torrent of condemnation and secular excommunication for thinking and speaking “wrongly.” It’s a short distance from “hate speech,” as defined by ever-changing criteria, to “hate crimes.”

How did Trump and other populist demagogues so easily claim large followings among free Americans? Manipulation and cynical appeals to fear and tribal instincts, yes. But millions of people also felt unheard, disregarded and disenfranchised by cultural elites. Frustrated and angry, they were ripe for the picking by a boorish loudmouth whom they might otherwise have ejected.

Independence Day approaches. In the best tradition of Roger Williams’ American dream of freedom, let’s allow each other to think and speak freely. It’s the only way to start climbing out of the divisive mess we’re in.

Erich Bridges, a Baptist journalist for more than 40 years, retired in 2016 as global correspondent for the Southern Baptist Convention’s International Mission Board. He lives in Richmond, Va.

Related articles:

Critical Race Theory, voter suppression and historical negation: The irony of it all | Opinion by Bill Leonard

‘Conscience … more or less’: Roger Williams, Mitt Romney and the rest of us | Opinion by Bill Leonard