I am one of the more than 40 million Americans eligible for President Joe Biden’s student loan forgiveness plan. I am also one of the 16 million Americans approved to participate in the program who may never receive the forgiveness it promises.

Legal challenges have paused the plan for a few weeks now, and the U.S. Supreme Court has just agreed to hear two of those cases in February. Until then, the fate of our student debt waits in limbo. I and several million others will spend that time praying our debt will be forgiven — something I already do several times a week as a Presbyterian pastor.

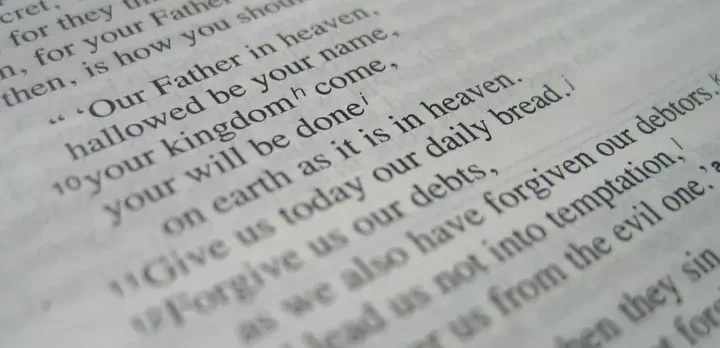

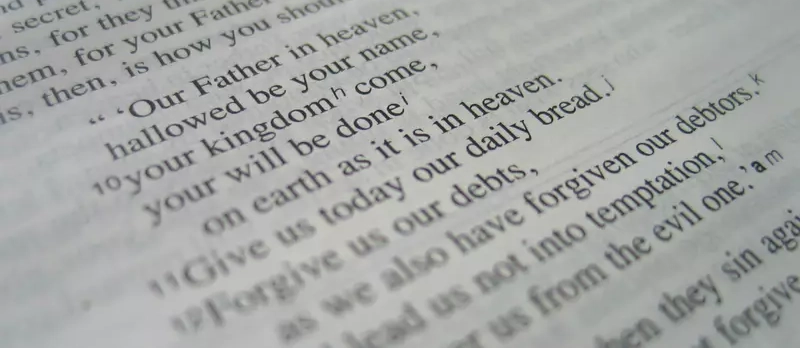

In the Lord’s Prayer in Matthew’s Gospel, Jesus teaches his disciples to pray “forgive us our debts, as we also have forgiven our debtors.” But for most English-speaking Christians with a tradition of reciting the Lord’s Prayer in worship, that line probably sounds unfamiliar. Instead, the most common iteration of the Lord’s Prayer in English contains the line “forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us,” with no mention of debt.

Keith Curl-Dove

The line “forgive us our debts, as we forgive our debtors” is almost exclusively recited in the Reformed tradition and among a handful of Congregationalists. Members of the Reformed tradition — the theological descendants of the Scottish Presbyterians and the Dutch Calvinists — make up less than 3% of the United States’ population. The rest of the English-speaking American Christians likely use “trespasses” in their liturgies. Occasionally you will hear an ecumenical compromise, praying for the forgiveness of sins.

Today, there is little conversation about whether we should pray for the forgiveness of debts versus trespasses in the Lord’s Prayer. Biblical translators consistently use “debts” in Scripture, while the liturgical use of the “trespasses” version is simply a matter of tradition. There is general consensus that both versions are metaphors for sin, which is why the most common ecumenical version says, “Forgive us our sins, as we forgive those who sin against us.”

At least in the United States, we often read Scripture in an almost exclusively spiritual fashion, with no substantial difference between debts and trespasses. Both terms are equally useful metaphors for sin, and we give little attention to the literal denotations. Materially minded readings of Scripture are less common, and there is quite a difference between debt and trespassing. In my own experience as a fly fisherman, hiker and someone who gets lost occasionally, others are usually quick to forgive trespasses. But as a person with loans, others are much more reluctant to forgive debt.

Jesus uses explicitly economic terms when he teaches his followers to pray. Jesus uses the words opheilemata and opheiletai in Matthew 6:12, which are accurately translated as “debts” and “debtors.” Ivoni Richter Reimer explains that these specific words “refer to the situation of monetary or economic debt, which had its origin in loans, wars or the nonpayment of taxes.”

“The Lord’s Prayer is nothing short of a prayer for the enactment of Jubilee, when debts were to be forgiven and prisoners set free.”

The Lord’s Prayer is nothing short of a prayer for the enactment of Jubilee, when debts were to be forgiven and prisoners set free. Debt can be a metaphor for sin, but first and foremost, debt means debt.

Debt, of course, encompasses much more than owing money, but it is very difficult to make the argument that Jesus, a poor Jew living under imperial occupation, would use the economical words “debts” and “debtors” without intending his listeners to think about financial debt. After the conclusion of the prayer, Jesus does use the word “trespasses” to explain the reciprocity of forgiveness, but the prayer itself speaks of debt.

Considering that his mother, Mary, sang of God sending the rich away empty and that Jesus is good news to the poor, praying for the forgiveness of real debt is consistent with the rest of his ministry. It is a peculiar phenomenon, then, that although Jesus taught his disciples to pray for the forgiveness of debt, most English-speaking Christians pray for the forgiveness of trespasses when asked to pray as Jesus taught.

Word choices concerning the topics of finance or religion are almost always intentional. The widespread use of the “trespasses” version of the Lord’s Prayer among English speakers can be attributed to the Church of England’s Book of Common Prayer, which has used “trespasses” since the publishing of the first edition in 1549. With centuries of use across the British Empire and Commonwealth, the Book of Common Prayer has had a marked effect on both English-speaking Christians and the English language in general.

The first Book of Common Prayer followed William Tyndale’s translation of Matthew 6:9-13, which erroneously uses “trespasses” instead of “debts.” The translators of the King James Version, published in 1611, corrected the prayer to the more accurate “debts,” but the official liturgy of the Church of England continued to use “trespasses.”

One of the most significant aspects of the Reformation was the translation of the Bible and church liturgy into the vernacular. At last, the regular people could understand the words in worship and Scripture. While the vernacular translations significantly improved literacy rates over time, most people could not read for themselves in the 17th century. This left them with the words they heard, rather than the words they read. As a result, the English subjects heard, recited and memorized the version of the Lord’s Prayer in the Book of Common Prayer, not the version in Scripture.

“The Church of England, with the British monarch as its supreme governor getting the final say, only taught people to pray about trespasses, not debt.”

The Church of England, with the British monarch as its supreme governor getting the final say, only taught people to pray about trespasses, not debt. As a rule, monarchs are not so keen on forgiving the debts of their subjects. Yet to the north in Scotland, an impoverished country heavily taxed by England and where Presbyterianism took root, debt was definitely something to pray about.

This past summer, Americans began to fear that the 6-3 conservative majority on the Supreme Court is pushing a conservative agenda based on “Christian values,” perhaps even feeding Christian nationalism. In partisan political rhetoric, “Christian values” are almost always void of Jesus’ own platforms of attention to the poor, debt forgiveness, radical inclusion and resisting empire.

Politicians promoting “Christian values” never campaign on a Jesus-based debt forgiveness plan or a platform of Jubilee. Instead, the politicians who are most proudly “Christian” are the ones most opposed to debt forgiveness. I can’t help but wonder if that would still be the case if they had learned Jesus’ version of the Lord’s Prayer, asking for and promising to enact the forgiveness of debts.

Praying as Jesus actually taught his disciples might not have much influence on those in power. The masses, though, would be significantly more likely to know where Jesus stands when it comes to debt forgiveness. That alone could push us to a more equitable economy for all.

In the meantime, I will continue to pray for the forgiveness of debts and do my best to forgive my debtors. Right now, it seems unlikely that I will ever see the forgiveness Biden’s plan promises, but I find hope in the Jesus who softens hearts, proclaims Jubilee and prays for the forgiveness of debts.

Keith Curl-Dove serves as pastor of New Creation Community Presbyterian Church and Faith Presbyterian Church in Greensboro, N.C. Among other things, he plays banjo, carves wooden spoons, and flyfishes the wild streams of the Blue Ridge Mountains.

Related articles:

On social media, the Bible verses are flying in a debate over student loan forgiveness | Analysis by Mark Wingfield

Many ministers saddled with seminary debt

The student loan forgiveness application should be the first step, not the last | Opinion by Brittini Palmer