On Thursday afternoon, March 18, 1937, in the Texas oil boom town of New London, 694 students and 40 teachers awaited the dismissal bell and the start of a special three-day weekend.

Then at 3:17 p.m., just 13 minutes before dismissal, New London School — a structure 253 feet long and 56 feet wide — imploded. The roof of the building was blown upward, the walls crumbled, then the roof collapsed, trapping students and teachers in the rubble of concrete, brick and twisted steel.

Many of the 294 children and faculty who were killed died instantly. Another 300 students were injured. Mother Francis Hospital in nearby Tyler, its grand opening scheduled for the following day, threw open its doors to receive the dying and the injured. Every vehicle became an ambulance.

Many of the 294 children and faculty who were killed died instantly. Another 300 students were injured. Mother Francis Hospital in nearby Tyler, its grand opening scheduled for the following day, threw open its doors to receive the dying and the injured. Every vehicle became an ambulance.

Churches, businesses, garages in New London and nearby communities of Henderson, Overton, Kilgore, Tyler and Longview were turned into first aid stations or makeshift morgues. “Grief-maddened” parents had to drive from town to town, searching for their children, dead or alive. Their anguish was heightened because many bodies were unrecognizable. Nevertheless, parents searched for anything that might identify their child — a birthmark, a shoe, a necklace, a slingshot in a jeans pocket.

A torrent of questions

Questions erupted: “How could this have happened?” and “Why did this happen?” Parents screamed, “Why God? Why here? Why innocent children?”

The reality could not be ignored: In just thirteen minutes, students would have been out of the building, walking or riding buses home.

Parents walk through a makeshift morgue in search for their children’s bodies.

Funeral directors from across East Texas showed up. Dallas dispatched 25 doctors, 100 nurses, and 25 embalmers. To meet the demand for child-sized caskets, employees of a Dallas casket manufacturer worked around the clock. And New London resident Graften Ferguson began building child-sized wood caskets.

Morticians embalmed more than 200 bodies in the Overton American Legion Hall over the next 18 hours. The deceased’s clothes were placed on the sheet covering the corpse. Some parents identified a son or daughter without viewing the entire body, some by recognizing home-sewn clothing or a scar.

That night, good hardworking “God-fearing” citizens screamed themselves hoarse as mangled bodies of children and teachers were pulled from the rubble. No one stopped when it began raining. It was as though heaven was weeping.

Within 17 hours, 2,000 volunteers had recovered all the bodies and completely stripped the site bare; 2,000 tons of rubble was hauled away.

The funerals begin

How does a community begin to ritualize the deaths of nearly 300 people on Palm Sunday weekend? A call for a mass grave and funerals offended grief-stricken parents. Even if funerals would have to be abbreviated, parents demanded traditional rituals and individual burial spaces to offer their children some semblance of dignity.

How does a community begin to ritualize the deaths of nearly 300 people on Palm Sunday weekend?

On Saturday, two days after the explosion, the first of dozens of funerals began in New London churches. Some of the dead were buried in new clothes parents had purchased for Easter Sunday. Funerals continued throughout Saturday and resumed on Sunday afternoon.

Pickup trucks serve as hearses for the funerals of those killed in the New London explosion.

Many funerals were held in the Old London Baptist Church, packed for each funeral with more mourners than pews could accommodate. A reporter later recalled being unable to stop staring at the five small caskets in front of the pulpit. As Texans sang “Rock of Ages, cleft for me,” tough wildcatters wiped away tears; others sat stoic, frozen.

At one joint funeral, the commander of the American Legion stepped to the pulpit and announced: “The roads are chocked with funerals today. The highway patrol has asked that friends not accompany the family to the cemetery.” That was a significant loss of tradition.

There were not enough hearses to transport the dead. After one funeral, as pallbearers carried two caskets to hearses parked outside the church, other pallbearers carried three caskets and placed them on mattresses in the back of flower-lined pickups. The crowd stood in silence as the hearses and trucks drove off to Pleasant Hill Cemetery. Then mourners re-entered the church for the next funeral. And again for the funeral after that.

Sixty-nine victims were buried side-by-side in Pleasant Hill Cemetery. Other children were buried elsewhere in Texas, Louisiana, Oklahoma and Arkansas.

‘What’s a preacher to say?’

Given the deaths of so many innocent children and the explosion’s impact on their bodies, pastors in funeral homilies — and in sermons over the following months and years — were expected to address mourners’ “whys.” Some attempted to explain God’s “mysterious ways.” How could preachers reconcile tragedy with lyrics most of the children sang by heart: “Jesus loves me, this I know … heavens’ gates to open wide.”

Rescue workers, parents and citizens sift through the rubble of the school hoping to find children and teachers alive.

The explosion, in the lyrics of a popular funeral song, seemed an outrageous way for God “to gather all his jewels.”

W.T. Bratton, pastor of New London Baptist Church, short-circuited traumatized believers’ questions with a firm two-pointer: “We can’t understand” and, “We shouldn’t question God’s ways.” Other preachers defaulted to shorthand theology: “God’s will.” One New London pastor declared that it had been “God’s will” to take “from our midst a great many of the dearest of our brethren.”

For grievers wanting a prooftext, Isaiah fit the bill: “For my thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways”? Some clergy and Sunday school teachers appropriated Job’s lament after the traumatic death of his 10 children, killed by a great wind that Scripture says “collapsed the house upon them.” Job had moaned, “The Lord gave, and the Lord hath taken away; blessed be the name of the Lord.” Job’s words — and the commentary on those words — comforted some mourners but confounded and annoyed others.

Some traumatized parents conceded, “The Lord gave” us these children but could not agree with the conclusion, “The Lord has taken away.” Some countered, “Well, the Lord certainly had permitted these 270 children to die. He could have prevented, or delayed, the explosion.

“Blessed be the name of the Lord” seemed an outrageous expectation.

Many grievers could not lament their dead because doing so would appear to question God’s “mysterious ways.” Even mildly protesting God’s actions would risk alienation from the church and the community.

Not until residents later became aware of the cause of the explosion could pastors amend their earlier sermons: “The fault is not God’s. It is man’s error.” Although “error” seems too timid an assessment of deliberate decisions.

A few pastors took to their pulpits to exegete Genesis 6:3, “My Spirit will not always strive with man.” They said the lives of innocent children “had been claimed” to pay for the sins and greed of the boom.

A righteous God, oil historians James Clark and Michel Halbouty noted, “had slaughtered lambs” because “corruption and lawlessness had gone unpunished.”

A righteous God, oil historians James Clark and Michel Halbouty noted, “had slaughtered lambs” because “corruption and lawlessness had gone unpunished.” Texans “had drifted away from God” as they got fat on the oil boom. “Now he had slaughtered the lambs in revenge.”

Michelle Holland, in a master’s thesis written at Baylor University, clarified the types of “debauchery typically associated with boom towns: thievery, shootings, gambling, prostitution, and bootlegging, adultery, and fornication.” No wonder, a righteous God had acted. The traumatized New London families — some having lost two or three children —were insulted, if not re-traumatized by well-meaning individuals distributing religious clichés to bypass the theological complexities of such a trauma:”‘She’s a precious flower for the Master’s bouquet” or “You can have another child.”

Clark and Halbouty, who studied the explosion, noted that “dark” interpretations taunted many grievers, particularly those with only a rudimentary understanding of faith. Moreover, some communities of faith relied on clichés or theological bypasses such as, “Preacher says ….” or “The Bible says …. .”

The very notion of a vengeful Creator blowing up children and teachers angered more than a few pious Texans. A few courageous grieving parents boldly challenged such theological assertions as “absurd” or “nonsense.” In time, some grievers found other things to do on Sunday mornings.

How had this explosion happened?

“How could this have happened to us?” and “How could a loving God allow this to happen?” percolated in the minds of individuals digging through the rubble and long afterward. New London School, built on the largesse of oil money, had been constructed for $1 million —during the Depression — and was the first school in Texas to have a football field with electric lights. To cut costs, however, the school board had left the long basement under the building unfinished, used only for shop classes.

Superintendent William Chesney Shaw

Answers soon emerged. William Chesney Shaw, the superintendent, wandered through the rubble, his face bleeding from flying glass, groaning, “There are children under here, there are children under here!”

Those children included Sambo, his 17-year-old son, a niece and a nephew.

Obviously, Shaw was not thinking clearly. So when a young reporter named Walter Cronkite asked him for details, Shaw tearfully “spilled the beans.” The school had been “appropriating” — stealing! — raw natural gas to heat the building.

Raw natural gas (or “wet gas”) is a byproduct of the drilling process. The gas has no odor and no economic value because it is too unpredictable. So in those days, oilmen burned it, a process called flaring.

Initially, United Gas Co. had supplied gas to heat the school for $300 a month. Abruptly in January 1937, to save money, Shaw and the school board sent janitors and a plumber to tap into a nearby oil company’s residue gas line. They laid pipes between drilling rigs and the school.

Aware their action was illegal, they rationalized that “everybody did it,” including local churches. Oil companies turned a blind eye to the practice. Due to a leak somewhere in the lines under the building, an estimated 6,000 cubic feet of natural gas had pooled, unnoticed.

Aware their action was illegal, they rationalized that “everybody did it,” including local churches.

Just before the dismissal bell that March day, Lemmie Butler, a shop teacher, turned on an electric sander he had repaired. That produced the spark that ignited the natural gas. And the New London School imploded.

And then …

Ten days after the explosion, classes resumed in the gym, in makeshift classrooms and in tents for an estimated 287 surviving students. Two years later, in 1939, a new school opened just yards from the original site. Since 1995, that building has been called West Rusk Consolidated.

The modern school building with the cenotaph nearby.

The community erected a large 70-foot-high granite cenotaph with victims’ names carved into the base of the monument. And today, on March 18, 2022, Texans will gather in New London for a service marking the 85th anniversary of the tragedy.

The New London explosion remains the greatest school disaster in American history — and it is a disaster that could have been avoided. Of course, lawsuits were filed, but all were dismissed. No one was found to be at blame for the tragedy.

Two heroes

In a death-denying society, Lynette Iezzoni laments that “as soon as the killing stops, the forgetting begins.” Today, school shootings and mass shootings are common but quickly forgotten. Details blur into the mosaic of contemporary violent American life. After a few days, the media moves on to wait for the next shooting.

In every trauma, individuals respond heroically. Whether in New London or somewhere today in Ukraine, heroes step forward to do what is needed. Two such heroes stand out in the New London narrative.

That fateful day, a bread deliveryman had arrived at New London School to unload bakery goods. The driver had parked far enough away from the school that he was not injured by the explosion. Immediately, he dumped the truck’s contents out on the grass. Then he began yelling to searchers, “Bring the children here!”

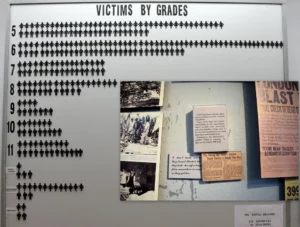

At the New London museum, a white board shows the tally of victims by grade.

When his truck was full, he sped off to the nearest hospital. As his truck was unloaded, a physician assessed each child. When the driver pointed to one 8-year-old girl, the physician snapped, “She is so near death it would be futile to waste time attempting to save her.” Despite the driver’s protests, the doctor turned to assist other children.

That driver picked up the small child, put her back in the truck and raced off to a hotel that had been converted into an emergency center. There he “insisted” — as only a Texan can —that this child be treated. Marie Beard lay in a coma for 10 days. Only then did she learn about an anonymous driver of a bread truck who had saved her life. She never learned his name.

Another hero’s name is known. Minutes before the explosion, school bus driver Lonnie Barber had picked up elementary students at New London School. He and his passengers were within sight of the school when the explosion happened. Barber resumed his two-hour bus route through rural Texas, intent on getting children home. He knew their parents would be “worried sick.” Only after all his students were safely home — and one mother threw a “Pentecostal shouting spell” when her child got off the bus — did Barber drive back to New London School to search for his own four children.

Late that night, a neighbor called out to Barber as he dug in the rubble. Upon learning that his son Arden’s body had been found, Barber walked back into the rubble and resumed digging. Barber’s other three children were not seriously injured.

One redemptive act resulted

To reduce future explosions, the Texas Legislature passed legislation mandating that thiols (mercaptans) be added to natural gas. Thus, that strong odor of rotten eggs made — and makes — leaks more detectable. The practice quickly spread worldwide.

As I watch the sobering coverage of the atrocities in Ukraine, I keep thinking of an unnamed bread truck driver who made a difference for at least one injured child. In Ukraine, as you read this, God is using unnamed persons.

My prayer is this: God, notice the unnamed heroes as they serve you in the unimaginable, the unjustifiable, the unbearable. Give them strength and courage sufficient for the demands of this day’s, tomorrow’s, and the day after tomorrow’s tragedies.

For more information see Gone at 3:17: The untold story of the worst school disaster in American history by David Brown and Michael Wereschagin.

Harold Ivan Smith

Harold Ivan Smith is thanatologist and independent scholar. For 18 years he served on the teaching faculty of Saint Luke’s Hospital in Kansas City, Mo. He earned graduate degrees from Scarritt College, Vanderbilt University, and a doctor of ministry degree from Asbury Theological Seminary. His writings include A Decembered Grief, On Grieving the Death of a Father; Grieving the Death of a Mother; When You Don’t Know What to Say; When a Child You Know Is Grieving, When Your People Are Grieving: Leading in Times of Loss.

Related articles:

As a pastor serves bread to the elderly in Ukraine, he prays to retain his humanity

‘Once America decided killing children was bearable, it was over’ | Opinion by Kathy Manis Findley

Parkland massacre takes pastor back to father’s mass shooting death