When Americans debate about immigration, they most often think of people coming from Mexico and other Latin American countries. Seldom do they first think of Black migrants.

Yet Pew Research Center reports that today one in 10 Black people in America were not born here. That 10% of the Black population that is foreign-born compares to 3% just 40 years ago.

Pew’s researchers summarize: “The Black population of the United States is diverse, growing and changing. The foreign-born segment of this population has played an important role in this growth over the past four decades and is projected to continue doing so in future years.”

That reality has implications for our language, our politics and our whitewashing of history.

The role of immigration policies

The changing nature of America’s Black population has been deeply influenced by changes to immigration policies. By most understandings, the first Black immigrants to the Americas in 1619 were involuntary immigrants — brought here by whites who were themselves voluntary immigrants from Europe or the descendants of those white immigrants.

Illustration of slaves being transported in the cargo hold of a ship in a space that is 3 feet, 3 inches high.

Thus, America’s Black immigration story is rooted in slavery.

This pattern lasted until 1810, when the importation of slaves was outlawed (even though the practice of slavery was not). Yet by 1810, U.S. Census data show, Blacks accounted for 19% of the nation’s population.

For decades after emancipation, most growth in the Black population in American came from the natural birth patterns of people who typically traced their lineage through the forced migration to early America as slaves. For generations, Black children born in America were born as Americans — even if not afforded the full rights and respect as citizens.

Throughout the 18th and early 19th centuries, America operated with relatively open immigration policies, according to documentation by U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. “After certain states passed immigration laws following the Civil War, the Supreme Court in 1875 declared regulation of immigration a federal responsibility. Thus, as the number of immigrants rose in the 1880s and economic conditions in some areas worsened, Congress began to pass immigration legislation.”

The Statue of Liberty (Photo by Noam Galai/Getty Images)

In response to the Immigration Act of 1891, the U.S. on Jan. 2, 1892, opened its well-known immigration processing center on Ellis Island in New York Harbor.

Immigration from Western European nations was prioritized, which slowed the voluntary migration of Black people to the U.S. for decades.

What happened in 1965

That changed with passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 that reduced the prioritization of immigrants from Western European nations and created new standards for evaluation. Also of note, this immigration act was passed just months after the landmark Voting Rights Act, which guaranteed minorities equal access to the ballot and is now the subject of Republican-led efforts to once again limit access to the ballot for persons who are minorities or who are poor.

President Lyndon B Johnson discusses the Voting Rights Act with civil rights campaigner Martin Luther King Jr. in 1965. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson predicted passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act would not have much practical effect. “It does not affect the lives of millions,” he said. “It will not reshape the structure of our daily lives.”

Yet it, in fact, did.

Ira Berlin of the University of Maryland wrote about this in Smithsonian magazine in 2010.

“At the time it was passed, the foreign-born proportion of the American population had fallen to historic lows — about 5% — in large measure because of the old immigration restrictions. Not since the 1830s had the foreign-born made up such a tiny proportion of the American people. By 1965, the United States was no longer a nation of immigrants.

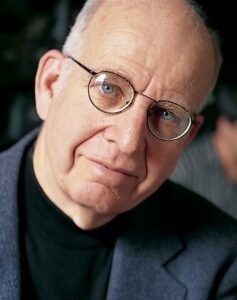

Ira Berlin

“During the next four decades, forces set in motion by the Immigration and Nationality Act changed that. The number of immigrants entering the United States legally rose sharply, from some 3.3 million in the 1960s to 4.5 million in the 1970s. During the 1980s, a record 7.3 million people of foreign birth came legally to the United States to live. In the last third of the 20th century, America’s legally recognized foreign-born population tripled in size, equal to more than one American in 10. By the beginning of the 21st century, the United States was accepting foreign-born people at rates higher than at any time since the 1850s. The number of illegal immigrants added yet more to the total, as the United States was transformed into an immigrant society once again.”

Berlin notes a similar transformation with Black America.

“Before 1965, Black people of foreign birth residing in the United States were nearly invisible. According to the 1960 census, their percentage of the population was to the right of the decimal point. But after 1965, men and women of African descent entered the United States in ever-increasing numbers. During the 1990s, some 900,000 Black immigrants came from the Caribbean; another 400,000 came from Africa; still others came from Europe and the Pacific rim. By the beginning of the 21st century, more people had come from Africa to live in the United States than during the centuries of the slave trade. At that point, nearly one in 10 Black Americans was an immigrant or the child of an immigrant.”

More changes since 1980

As previously noted, these trends expanded with passage of the Refugee Act of 1980 and the Immigration Act of 1990.

Thus, since about 1980, the migration of Black adults and children from other countries has accounted for an increasing share of the nation’s Black population. In 2019, that was true of 4.6 million Black people in the U.S.

“Before 1965, Black people of foreign birth residing in the United States were nearly invisible.”

Pew Research adds: “Between 1980 and 2019, the nation’s Black population as a whole grew by 20 million, with the Black foreign-born population accounting for 19% of this growth. In future years, the Black immigrant population will account for roughly a third of the U.S. Black population’s growth through 2060.”

That would mean 9.5 million Black citizens who were not born in America.

That would mean 9.5 million Black citizens who were not born in America.

Further: “The Black immigrant population is also projected to outpace the U.S.-born Black population in growth. While both groups are increasing in number, the foreign-born population is projected to grow by 90% between 2020 and 2060, while the U.S.-born population is expected to grow 29% over the same time span.”

An immigration story

This, then, is an immigration story — and a story that mixes two of the greatest challenges to white supremacy: immigration and race.

Berlin summarizes his own observations: “After devoting more than 30 years of my career as a historian to the study of the American past, I’ve concluded that African American history might best be viewed as a series of great migrations, during which immigrants — at first forced and then free — transformed an alien place into a home, becoming deeply rooted in a land that once was foreign, even despised.”

It’s easy to connect the dots to link America’s immigration story with the timeline of the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s to the election of Donald Trump as U.S. president on a strident anti-immigrant platform with not-so-subtle racist overtones. Trump once declared the U.S. needed fewer immigrants from “shit-hole countries” and more from places like Norway. Norway’s population is 91% white.

“Given the numbers of Black immigrants arriving after 1965, and the diversity of their origins, it should be no surprise that the overarching narrative of African American history has become a subject of contention,” Berlin concluded six years before Trump was elected president.

Where are the people coming from?

Modern-day migration from Africa has accounted for the majority of growth in America’s Black foreign-born population since 2020, Pew reports.

“In 2000, roughly 560,000 African-born Black immigrants lived in the U.S. By 2019, that number had more than tripled to over 1.9 million. And many of these immigrants are newer arrivals to America: 43% of African-born Black immigrants came to the U.S. from 2010 to 2019, higher than the shares among all U.S. immigrants (25%) and Black immigrants from the Caribbean (21%), Central America (18%) and South America (24%) in the same time period.”

“In 2000, roughly 560,000 African-born Black immigrants lived in the U.S. By 2019, that number had more than tripled to over 1.9 million. And many of these immigrants are newer arrivals to America: 43% of African-born Black immigrants came to the U.S. from 2010 to 2019, higher than the shares among all U.S. immigrants (25%) and Black immigrants from the Caribbean (21%), Central America (18%) and South America (24%) in the same time period.”

Among African immigrants, the largest share (348% growth) is from Kenya, followed by a nearly 300% increase from Ethiopian-born immigrants. Other top countries of origin are Somalia (205% increase), Nigeria and Ghana (200% increase each).

There’s a spinoff effect of this trend too: About 9% of Black people are second-generation Americans, meaning they were born in the U.S., but have at least one foreign-born parent.

And there are well-known examples of this, most notably former U.S. President Barack Obama, who was born to a Kenyan father and American mother. Also former Secretary of State Colin Powell, the son of Jamaican immigrants.

“In total, Black immigrants and their U.S.-born children account for 21% of the overall Black population,” Pew reported.

Overall, two regions — the Caribbean and Africa — account for 88% of all Black foreign-born people in the United States in 2019. From the Caribbean, Jamaica and Haiti are the two most frequent countries of origin, accounting for 16% and 15% of Black immigrants, respectively. About 8% of Black immigrants (8%) were born in South America, Central America or Mexico, while 2% are from Europe and 1% from Asia.

Differences in origin stories

Demographic research shows some notable differences between foreign-born Black citizens and American-born Black citizens. For example, Pew notes:

- A larger share of Black immigrants ages 25 and older have a college degree or higher than does the U.S.-born Black population (31% vs. 22%). However, Black immigrants are about as likely as all U.S. immigrants in the same age group to have a college degree or higher (31% and 33%, respectively).

- Households headed by Black immigrants also had a higher median household income in 2019 than those headed by Black Americans born in the U.S. ($57,200 vs. $42,000), but the median household income was higher among all U.S. immigrant-headed households than it was among Black immigrant-headed households ($63,000 vs. $57,200).

- More than half of Black immigrants born in the Caribbean (56%), Central America or Mexico (59%) and South America (54%) have been in the U.S. 20 years or longer, while just a quarter of Black African immigrants have been in the country for the same time span.

And there’s one other difference between Black citizens born in America versus those born elsewhere before migrating to America: religiosity.

And there’s one other difference between Black citizens born in America versus those born elsewhere before migrating to America: religiosity.

Pew’s report explains: “While Black adults who are either U.S. born or U.S. immigrants are more likely to identify as Protestant than any other religion, a larger share of the U.S.-born Black population identifies as Protestant. About seven in 10 Black U.S.-born adults are Protestant (68%), while 53% of the Black immigrant population has this religious affiliation.

“A larger share of Black immigrant adults are Catholic than their U.S.-born Black counterparts (19% vs. 5%), and a slightly smaller share are unaffiliated with any religion (18% vs. 22%).”

Related articles:

How we’re learning to see and hear the Black experience at Colonial Williamsburg | Analysis by Ella Wall Prichard

The plantation lived on through Texas Baptist evangelism | Analysis by Laura Levens

The big news from the 2020 Census is multiculturalism, which threatens some people and still eludes most churches | Analysis by Mark Wingfield