In the decade following the Second World War, the United States experienced an unprecedented religious revival. In 1958, more than 50% of Americans claimed to have attended a worship service in the previous week. By every conventional measure, the nation was more religious at mid-century than at any time before or since.

Mid-century America was the golden age of American religion. Scores of pastors, priests and theologians were revered, even celebrated. Sermons from celebrated preachers appeared in prominent newspapers. Denominational barriers appeared to be eroding. The nation was uniting around a simple God-and-country form of civil religion. The leaders of American Mainline Protestantism didn’t approve every feature of this revival, but they stood at the heart of it.

The fundamentalists retreat

Mainline Protestantism triumphed at mid-century because conservative Christians were in full retreat. When the Scopes trial ended in 1925, Protestant America was ensconced in a nasty food fight between “modernists” like the celebrated pulpiteer Harry Emerson Fosdick and “fundamentalists” like Minneapolis preacher W.B. Riley. The fight highlighted issues such as Darwinian evolution, the “virgin birth” and the divine inspiration of the Bible.

William Jennings Bryan

But what kept men like William Jennings Bryan awake at night was the vision of devout young college students losing their religion. If academic elites were made the final arbiters of truth, fundamentalists reasoned, the churches would soon forfeit their traditional place in society.

In the early 1920s, Bryan was voicing his concerns on the Chautauqua circuit and at religious conferences and on the campuses of liberal institutions like Harvard and the University of Chicago. Preachers like W.B. Riley, J. Frank Norris in Fort Worth, T.T. Shields in Toronto, A.C. Dixon in Baltimore, R.A. Torrey in Los Angeles, J. Gresham Machen of Princeton Theological Seminary, and John Roach Straton in New York City swelled the chorus of alarm.

Liberal preachers and academics were concerned about the fate of college students, too, but for very different reasons. There was no sense asking biologists and German biblical scholars to conform their views to literal text of the Bible, liberals insisted. The Christian faith must adapt to new knowledge.

J. Gresham Machen

Their shared belief in an inerrant Bible didn’t protect fundamentalists from fracturing internally. While most fundamentalists were politically conservative, Bryan was a social gospel liberal. Machen was a highly respected biblical scholar who avoided the anti-evolution fight. When it became clear that his fellow Presbyterians didn’t share his dedication to the “Princeton theology” of men like Archibald Alexander, Charles Hodge and B.B. Warfield, Machen founded his own seminary and established his own denomination.

The ultra-conservative faction couldn’t even agree on how the world would end. This was problematic because preachers like Norris and Riley emphasized the imminent rapture of the church and a host of similar doctrines associated with “premillennial dispensationalism.” Like Bryan, Machen was solidly postmillennial. Shields was amillennial. This eschatological muddle frustrated cooperation among leading fundamentalists.

With the death of Bryan in 1925, the fundamentalist movement quickly fractured into rival camps. Pastors like Riley, Norris and Shields created thriving fiefdoms but never were able to forge a unified conservative front. Having failed to rally the Northern Baptist Convention behind his cause, Riley concentrated on his own church, his Bible school and his evangelistic work.

J. Frank Norris

J. Frank Norris’ decades-long assault on theologically conservative Texas Baptists like George Truett and L.R. Scarborough also came to grief. T.T. Shields’ attempt to root out heresy in McMaster University and the Baptist Convention of Ontario and Quebec fared no better.

Fundamentalists prospered within their own social units but, between 1925 and 1960, they were effectively exiled from mainstream American culture.

The conservative exodus from the Protestant Mainline left Social Gospel liberals in charge. In 1925, Canadian Methodists, Presbyterians and Congregationalists combined to create the United Church of Canada. Attempts at organic church union failed in the United States, but the Federal Council of Churches allowed American Mainline Protestantism to speak with a common voice.

Although the Southern Baptist Convention adopted a statement of faith in 1925, most denominational officials were determined to keep firebrands like Norris (and liberals, whenever they could find one) in check.

Harry Emerson Fosdick

Harry Emerson Fosdick, celebrity preacher

Harry Emerson Fosdick was pastor of First Presbyterian Church in New York City in 1922 when he preached his most famous sermon: “Shall the Fundamentalists Win?” Faced with a world in desperate need of the Christian gospel, Fosdick asserted, it was shameful for followers of Jesus to be arguing over “the tiddledywinks and peccadillos of religion.”

Fosdick said he had no desire to silence fundamentalists, but it appeared the fundamentalists were determined to silence everyone who disagreed with them. And if they succeeded, “then out of the Christian church would go some of the best Christian life and consecration of this generation — multitudes of men and women, devout and reverent Christians, who need the church and whom the church needs.”

By 1922, Fosdick was a household name. His sermons were frequently printed in The New York Times and other newspapers, and his books on practical Christianity were bestsellers. His celebrity explains why the conservative faction within the Presbyterian Church (USA), led by Bryan and Machen, were determined to force him out of his prestigious pulpit. Realizing that keeping his post meant submitting to a heresy trial, Fosdick quietly tendered his resignation.

No one doubted the celebrity preacher would land on his feet. “Such a voice as that of Dr. Fosdick’s is in no danger of being silenced by any technical ecclesiastical veto,” The New York Times editorialized. “He has but to speak, anywhere, and people will flock to hear him.”

Fosdick was immediately called as pastor of the newly formed Park Avenue Baptist Church. In 1930, largely thanks to John D. Rockefeller’s money, Riverside Church was constructed in New York’s fashionable Morningside Heights neighborhood, largely as a stage for Fosdick. Located across the street from Union Theological Seminary (where Fosdick taught homiletics) Riverside quickly became the unofficial flagship of American Mainline Protestantism.

Reinhold Niebuhr

Fosdick’s Social Gospel liberalism was challenged by Reinhold Niebuhr, Fosdick’s eventual colleague on the Union Seminary faculty. Although still a committed socialist with pacifist leanings, Niebuhr savaged Social Gospel liberals for their naïveté concerning the human potential for sin, especially of the corporate variety. Human institutions, Niebuhr asserted, are inevitably hamstrung by pride and moral compromise.

In a 1935 sermon titled “The Church Must Go Beyond Modernism,” Fosdick admitted that modernists, in their haste to harmonize their theology with modern science, had grown too accommodating to the dominant culture. Although Fosdick had little use for the intricate vagaries of Christian doctrine, he never questioned the transforming power of God. In 1902, while a student at Union Seminary, he suffered an emotional collapse that left him teetering on the verge of suicide. Fosdick cried out to God and, to his surprise and relief, the young theologue encountered the transforming grace of God.

Fosdick wanted to help people in much the way he had been helped. He preached for results, asking his listeners to question their priorities and make hard decisions. A keen student of psychology, Fosdick spent almost as much time counseling parishioners as he invested in his preaching. Fosdick always regarded himself as an evangelical Christian. He treated the crude materialism of religious skeptics like Bertrand Russell with the same harsh treatment he generally reserved for the hyper-orthodox.

Celebrity theologians

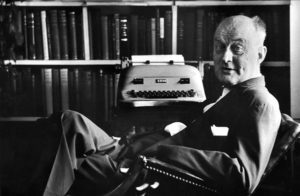

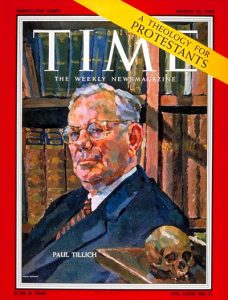

In 1933, Paul Tillich lost his professorship at the University of Hamburg in the Nazi purge of socialist intellectuals. Invited by Niebuhr to join the faculty at Union Seminary, Tillich accepted. By mid-century, three members of Union’s faculty (Fosdick, Niebuhr and Tillich) would grace the cover of TIME magazine. This was the golden age of the Christian intellectual.

Paul Tillich

Niebuhr rose to national prominence during and after the Second World War. His concept of “Christian realism” helped a generation of Christian preachers, professors and politicians harmonize their passion for peacemaking with the urgent need to confront fascism and Soviet-style communism.

Tillich’s existential theology created a sensation in elite academic circles. Following the insights of Soren Kierkegaard and Martin Heidegger, Tillich started with the human condition. We have been given the gift of being but, unlike other creatures, we are plagued by the knowledge of non-being. It is essential, therefore, that we discover “the courage to be” (the title of his most famous book). Everyone deals with this crisis of existence by embracing an “ultimate concern,” which may be God, but is more likely to be an idolatrous substitute for God.

God should not be regarded as one being among other beings, Tillich insisted. God is the “ground of being.” No one was sure what the German intellectual meant by this formulation. Was he saying God didn’t exist? Or was he merely echoing Thomas Aquinas’ belief that we exist in God? No one was quite sure, and Tillich’s calculated imprecision made him as popular with agnostics as with devout Christians.

There was a mystical quality to Tillich’s thinking. Because God is beyond human comprehension, he said, we can only say what God is not.

Wherever Tillich lectured, the hall was packed to overflowing.

Tillich, Niebuhr and Fosdick all stressed the critical difference between faith and national identify. Having been caught up in the patriotic jingoism that came with America’s entry into the First World War, Fosdick was an avowed pacifist throughout his later ministry. Following the lead of his pacifist friend George Buttrick, Fosdick opposed American involvement in the Second World War.

Although Niebuhr initially criticized Roosevelt’s military build-up in the late 1930s, he performed a dramatic about-face once the shooting started. His concept of “Christian realism” was formed in response to the Nazi threat and, after the war, the spread of Soviet communism.

Having narrowly escaped the arbitrary brutality of Nazi Germany, Tillich enthusiastically participated in anti-Nazi “Voice of America” broadcasts.

Tillich and Niebuhr both have been tied to the Neo-Orthodox tide that rolled over America between 1925 and 1960. In retrospect, neo-orthodoxy was a form of pastoral theology that allowed educated Christians to claim continuity with the Protestant Reformation without surrendering to fundamentalist obscurantism. God cannot be found in nature, Karl Barth insisted, or even in the Bible; only in Jesus Christ can the Word of God be found. This formulation helped ease the tension between Protestant orthodoxy and the “historical critical” study of the Bible.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt addressing the nation.

The domestication of American religious media

The period from 1925 to 1960 was an age of confluence and consensus. The harsh deprivations of the Great Depression, the communal sacrifice of a second World War and Cold War anxiety all encouraged wagon-circling solidarity. “The defense of religion, of democracy and of good faith among nations,” Franklin Delano Roosevelt insisted in 1939, “is all the same fight.”

Father Coughlin (Photo: Library of Congress)

In the same year, Roosevelt demanded that Father John Coughlin, the radio preacher who had become the president’s most deadly adversary, be stripped of his broadcast license. The Federal Communications Commission meekly complied. A Catholic priest, Coughlin was one of the first religious figures to build a mass following through radio. Initially an enthusiastic booster of Roosevelt’s New Deal policies in the early years of the Great Depression, Coughlin eventually became enamored of fascist strongmen like Benito Mussolini and Adolph Hitler.

By 1939, more than 30 million Americans (a quarter of the U.S. population) were tuning in to Coughlin’s program. The Catholic firebrand’s wild accusations could easily be dismissed by informed people, but in 1935, only 5% of adults had a college degree, and most hadn’t completed high school.

Although he was a Catholic priest, Coughlin’s message dovetailed neatly with the views of prominent fundamentalists like W.B. Riley. The Minneapolis preacher’s admiration for Coughlin’s brand of American fascism was so unbounded that, in 1935, Riley circulated a pamphlet written in praise of Coughlin. In 1933, Riley quoted Hitler himself in support of Coughlin’s antisemitism. Like J. Frank Norris’ close identification with the Ku Klux Klan a decade earlier, Riley’s Christo-fascism tarnished the fundamentalist brand.

Major broadcasting companies like NBC and CBS didn’t have to be convinced Coughlin was a problem. As early as 1933, the broadcasting industry had introduced a strong dose of quality control into its religious programming. According to the new standards, Catholics, Protestants and Jews would enjoy free and equal access to the airwaves with the proviso that Catholic speakers would be selected by the National Council of Catholic Men, Jewish programing would be left in the hands of the Jewish Seminary of America, and Protestant representatives would be chosen by the Federal Council of Churches. When television broadcasts began in the early 1950s, the same standards applied.

Riverside Church made the most of this environment. Since the late 1920s, Fosdick had served as the senior minister on NBC’s nondenominational Protestant radio program, “National Vespers.” Robert McCracken inherited this role when he succeeded Fosdick as Riverside’s pastor in 1946.

Fundamentalist preachers were left in the cold. They could, and did, buy time on local radio stations, but generally were relegated to what Baptist humorist Grady Nutt called “the weird end of the dial.”

Speaking in precise, never stagey tones, Bishop Sheen discusses a variety of subjects. His only prop is a blackboard on which he draws simple diagrams to help the audience grasp more easily the philosophical points he is making. (Getty Images)

Monsignor Fulton Sheen, a debonair and highly educated Catholic parish priest, was one of the first religious figures to take advantage of this new love affair between mainstream religion and mainstream media. Affable and sincere, Sheen spent 30 hours each week preparing his radio sermons, translating his presentations into German and Italian as an aid to memory. On camera, he spoke fluently without notes. When he made the transition to television, Sheen appeared in his full clerical regalia, with nothing but a shelf of books and a blackboard for props. Judging from the flood of letters that arrived from listeners every week, two-thirds of Sheen’s avid listeners were Protestant.

Following the publication of his 1952 bestseller, The Power of Positive Thinking, Norman Vincent Peale, the popular pastor of New York’s Marble Collegiate Church, became a media darling. Like Fosdick, Peale addressed the emotional concerns of his audience, but he lacked Fosdick’s nuance, polish and intellectual prowess. Peale’s popularity rested in the unvarying simplicity of his attitude-is-everything message. The apostle of positivity was particularly popular with the business class and with those who aspired to affluence.

The religious programming of the postwar period was designed for mass appeal. Patriotic boosterism and critiques of godless communism proved to be highly marketable commodities that offended hardly anyone. Institutional religion was promoted as wholesome, positive and practical. Sectarian specificity was discouraged.

Charles Templeton was the first host of the CBS television program “Look Up and Live.” The National Council of Churches selected the Canadian evangelist for this role because he looked good on camera.

In an early half-hour episode from 1954, the word “God” didn’t appear until the 25th minute. Aired on Sunday morning, the program was aimed at unchurched young people. A racially integrated quartet in military uniform opened the show with a humorous ditty about a battleship captain and his shipmates. Next, Templeton used a battleship replica as an object lesson. The 5-minute “sermon” presented religion as a sure-fire antidote to the hardships of life. In the final segment, Templeton slipped on a clerical robe and stole before declaring, “Well, I’m on my way to church. Why don’t you join me?”

Charles Templeton, Torrey Johnson and Billy Graham in a publicity photo for the European trip taken in the YFC offices in Chicago. Ca. March 1946. (Billy Graham Center Archives, Wheaton College)

Templeton began his evangelistic career touring postwar Europe with a young Billy Graham, but the two men eventually parted ways. Templeton began to question the evangelical piety he had imbibed as a young man and enrolled in Princeton Theological Seminary. In 1949, just as Graham was preparing for his first major crusade in Los Angeles, Templeton gave his old friend the bad news: the sin-and-salvation message they had preached in Europe was hopelessly out of date. If Graham really wanted to address the needs of mid-century America, he needed to get a seminary education.

Billy Graham captures the Protestant Mainline

Billy Graham often lamented his lack of theological training, but the curriculum of most Mainline Protestant seminaries would have shaken his confidence and blunted his effectiveness. Graham preached a simple gospel message because, like the working-class men and women who flocked to hear him, it was what he knew.

When he made a simple appeal to biblical authority, people responded. By the millions. His fans knew what he was going to say before he said it; but his predictability was why they filled arenas and football stadiums night after night.

For Graham, everything came down to a simple decision for or against Jesus. But he wasn’t simply counting converts; he wanted to spark a national religious awakening. This ambition distanced Graham from the separatist sectarianism that had shaped his early faith. The decision cards that were evaluated after every major crusade showed Graham’s audience included Catholics and Mainline Protestants as well as conservative evangelicals. Graham kept his message simple so he could grow his audience as big as possible.

Graham’s big breakthrough came in 1957 when 800 congregations in New York City, most of them affiliated with the Protestant Mainline, invited him to hold revival meetings in Madison Square Garden and a host of other venues throughout the New York area.

Although Riverside Church and Union Seminary provided cautious support for the Graham crusade, Reinhold Niebuhr withheld his blessing. Niebuhr argued that Graham’s singular focus on individual conversion revealed a fundamental misunderstanding of the systemic nature of sin.

Although Riverside Church and Union Seminary provided cautious support for the Graham crusade, Reinhold Niebuhr withheld his blessing. Niebuhr argued that Graham’s singular focus on individual conversion revealed a fundamental misunderstanding of the systemic nature of sin.

Henry Van Dusen, president of Union Seminary, gently chided his celebrity professor. Many of Union’s students had become Christians in response to Graham’s preaching, Van Dusen noted. He even admitted that he had come to faith at a Billy Sunday revival.

While in New York, Graham tried to arrange a meeting with Niebuhr, but the famous professor refused to see him. Graham told reporters he had read every book Niebuhr had written and had benefited greatly from his insights. There is no reason to doubt this statement. Niebuhr’s critique of liberal religion and Soviet communism, and his steady focus on human sin, would have resonated with the preacher from North Carolina.

Van Dusen realized that Union Seminary, Columbia University and well-heeled congregations like Riverside appealed to high-status folk who, in all likelihood, would be under-represented at a religious revival. But Graham was reaching people Riverside and Union never would touch.

America’s mid-century religious revival had something for everybody.

Marquee at Madison Square Garden in 1957 (Billy Graham Archives)

In a book published in 1961, Fosdick praised Graham for integrating his crusades. While preaching in Nigeria, Fosdick reported, Graham had admitted to a Nigerian pastor that Christian worship in America is almost always segregated. “God help our Christian enterprise here in Africa,” the Nigerian pastor responded, “if our people ever find that out!”

Graham believed every bit of the old-school theology Fosdick had long abandoned, but the Baptist preachers both emphasized the transforming power of God and the necessity of decision. Game recognizes game.

Graham spoke 97 times in the course of the New York Crusade, including a service in Times Square that drew 125,00 people. Graham even invited a young Black pastor from Montgomery, Ala., to lead in prayer. His name was Martin Luther King Jr. And when Ethel Waters, the Black Broadway singer, rededicated her life and joined Cliff Barrows’ choir, Graham invited her to favor the Madison Garden choir with her signature song: “His Eye is on the Sparrow.” Waters would sing that song, virtually nonstop, at Graham crusades until her death in 1977.

By the time the New York crusade ended, Billy Graham had become the smiling, confident face of American religion. To virtually all evangelicals, most Mainline Protestants and many Catholics, Graham’s simple message was the essence of Christian faith. Seminary educated preachers might find fault with Graham’s approach, but they learned to keep their opinions to themselves.

One nation under God

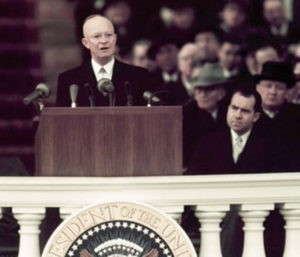

At mid-century, the acolytes of American organized religion had achieved iconic status and an anxious nation had embraced a generic brand of civil religion. Coughlin-style paranoia still flourished in the shadows, but when Joseph McCarthy accused liberal clergymen of complicity with the communist foe, President Eisenhower cried foul.

President Dwight D. Eisenhower giving his inaugural address in 1953.

With Eisenhower’s blessing, America added the words “under God” to the Pledge of Allegiance in 1954 and affixed the phrase “in God we trust” to its money in 1956. These fragments of civil religion were consistent with the First Amendment, the Supreme Court ruled. Being purely ceremonial, they were devoid of significant religious content.

But for many Americans, these carefully placed expressions of civic piety were far from ceremonial. They meant that America, in contradistinction to the communist world, rested on the foundation of religious faith. Eisenhower said it best: “Our form of government has no sense unless it is founded in a deeply felt religious faith, and I don’t care what it is.” To which he hastily added, “Of course, it is the Judeo-Christian concept, but it must be a religion with all men being created equal.”

Graham’s New York Crusade was entirely consistent with Eisenhower’s idealism. Liberal and conservative congregations banding together to invite a Bible-believing, Niebuhr-reading, country preacher to speak in Madison Square Garden with a Black preacher leading in prayer and a Black soloist leading the choir. At long last, America was living up to the opening line of the Declaration of Independence. As subsequent events would prove, the truth was a bit more complicated. That’s for next time.

Alan Bean

Alan Bean serves as executive director of Friends of Justice. He is a member of Broadway Baptist Church in Fort Worth, Texas.