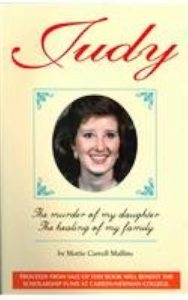

The first time I saw Judy Mullins, everything shifted into filtered slow motion like a scene from a teen movie. I was a high school senior attending a combined high school and college Sunday school class when she — a university student — flooded the room with angelic aura and breathtaking beauty.

Alabaster skin. Radiant red hair. Sea-blue eyes. Serene gaze. She was a religion major who became president of the ministerial association, quite an accomplishment for a female at a small Tennessee Baptist university in the 1980s.

Russell Freels as drum major at Jefferson County High School.

She met Russell Freels at that same university where both his father and mine were professors. Russell, a year older than I, had been drum major for our high school band. Other than two very brief encounters, I knew almost nothing about Russell. We never hung out, since his family went to the local Methodist church rather than the unofficially official Baptist congregation adjacent to campus where my family attended.

Prior to my own family moving to another church, in my childhood mind, if someone wasn’t a member of First Baptist Church, it was questionable if they were even Christians.

Even as a college sophomore, my suspicions were compounded when Russell and I had a conversation. He boasted that he had never paid the small annual fee for a parking pass. Since he never registered his vehicle, he just parked in visitor parking. I thought the mischievous sparkle in his eye was odd. I remember thinking, “Dude. As dependents of professors, we’re on tuition waiver. Just pay the fee.”

Judy and Russell married in 1987. A few years later, in 1993, I was just out of seminary and visiting my grandparents near Judy’s hometown when I saw the news that Judy had been brutally stabbed to death outside her parents’ home. With her that night were her and Russell’s infant and toddler sons.

The toddler awakened his grandparents and said a monster had hurt his mother and she was melting in the snow — a toddler’s glass-door view of his mother bleeding to death. Since Judy had stepped outside in her bathrobe in the freezing cold, authorities quickly reasoned she likely was killed by someone she knew.

The toddler awakened his grandparents and said a monster had hurt his mother and she was melting in the snow — a toddler’s glass-door view of his mother bleeding to death. Since Judy had stepped outside in her bathrobe in the freezing cold, authorities quickly reasoned she likely was killed by someone she knew.

Until I read Judy’s mother’s book much later, I didn’t know those details. At the time of the murder, when I saw a TV news interview with Judy’s parents and Russell, I made a call to my family and told them, “I hate to say it, but something was odd about Russell and the way Judy’s father looked at him when he was speaking during the interview. I think Russell might have been involved.”

It was a brutally heinous murder, actually carried out by some of Russell’s friends to whom he promised a portion of Judy’s life insurance policy. Later I learned Russell had gotten deeply into drugs and alcohol. He eventually would describe to me his teen and young-adult self as a Christian in name only.

He says he played the role but was devoid of morality. Amidst this moral void, he got his mistress pregnant and rashly decided to kill Judy and start a new life.

“I noticed he was dabbing his eyes with a wad of tissue even though there were no tears.”

Before Russell’s involvement was confirmed, I went to Judy’s funeral, where Russell cried loudly. In the foyer after the funeral, Russell and I greeted each other with a hug. I noticed he was dabbing his eyes with a wad of tissue even though there were no tears.

‘Your only offer’

Not long after, the prosecutor abruptly offered Russell a deal. Russell recently told me that 10 days before the murder, a new Tennessee law had gone into effect, making murder-for-hire equal to committing first-degree murder. The DA bluntly told Russell he could take life without parole or face the death penalty, concluding, “This will be your only offer.”

How does anyone — much less a drug addict — make a clear decision in that circumstance? How do we strike the balance between justice and redemption? If a drug addict makes the worst possible mistake of killing, can we execute our justice system when it often makes mistakes in killing the wrongly convicted? What do we mean by “Department of Corrections”? Is the prison atmosphere conducive to correction?

For example, after my experience getting through prison security check points, it is beyond my imagination that there is a drug pipeline in prisons. Yet, there is, and Russell told me that even in prison, he spent the first seven years still a drug addict. He also had a reputation as a brawler. He’s not a particularly big guy. One of his prison chaplains told me, “Those first few years, he would get the wax beaten out of him, but the other guys knew they’d been in a fight.”

High school senior portrait of Russell Freels fro Jefferson County High School, 1983.

Russell’s mother died early on in his sentence. It seemed clearly connected to the stress of the tragedy. Yet his father faithfully came to visit him. While Russell had grown up in a Christian family, faith never had been more than an obligation to go to church with his parents.

Due to his father’s commitment, Russell eventually took what Kierkegaard called a “qualitative leap” (commonly called a leap of faith) to let spirituality transform his inner self. In his case it was through what he describes as a now genuine commitment to following Christ. He devoted himself to prayer, meditation and studying Scripture.

A late start

I started writing him letters when he had been in prison about 13 years. I apologized for it taking so long but that being on our old campus, he kept coming to mind.

He wrote back a kind letter and said if my letter had come any earlier, he likely would have ignored it, unready to face others. Despite his saying he would have ignored me, I felt a healthy amount of guilt realizing that regardless of his reaction, I was only responsible for making the effort.

Eventually I went to visit him — an experience described in an essay in Spirituality & Health. The relationship has deeply impacted my life.

“About an hour into our three-hour visit, he said that other than his father and some chaplains, I was the only person to ever come see him.”

At that first visit, I finally tracked him down at Unit 2 for prisoners with years of good behavior. About an hour into our three-hour visit, he said that other than his father and some chaplains, I was the only person to ever come see him. He asked why I had come. In my Spirituality & Health essay, I described my response this way:

After an awkwardly long pause, I began, “I want to be honest.”

He nodded.

Working up the nerve, I finally spit out the word, an awkward confession: “Duty.” I raised my eyebrows and shrugged. “Jesus said, ‘I was in prison, and you visited me.’ It’s what I’m supposed to do.”

He nodded.

I continued, “And … so many things from our hometown kept reminding me of you. I started wondering what change in the wind would have led me to be out there and you in here. And if our situations were reversed, I would want you to come see me.”

He nodded, seeming to appreciate my honesty.

From duty to transformation

What started as duty, bloomed into — as it almost always does — receiving far more than I have ever given.

Russell’s job in the prison is serving as assistant to the chaplain. He works 16- to 18-hour days studying and leading Bible study and support groups. I have seen numerous mothers, wives, girlfriends and daughters of prisoners come up to Russell in the visitation room, take his hands in theirs and gush, “Thank you so much for how much you are helping my (son, husband, boyfriend, father). He is such a better man because of you.”

A few months ago, I heard directly from one of the men when I received a call from Greg, one of Russell’s longtime mentees. Greg had just arrived at a halfway house after 15 years in prison. For several minutes, he described how much Russell had helped him rehabilitate his life.

I, too, have been a beneficiary of his ministry. I currently have several pastors in my life. Two are at churches affiliated with the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship — one locally and one in Virginia I started attending virtually during the pandemic. Others are at a local Methodist church I started attending because my son loved the youth program. Then there is Russell, my pastor at Bledsoe County Correctional Complex in Smack-Middle-of-Nowhere, Tennessee, an hour of snaking mountain roads south of my home in Cookeville.

“His use of Scripture is never weaponized.”

Russell is a deeply attentive and compassionate listener. He can quote copious amounts of Scripture. Here’s the thing though: His use of Scripture is never weaponized. It is always gentle guidance informed by the many books he has read on hermeneutics and pastoral care.

Generosity? Among many such activities, Russell helps lead the “Lifers’ Club” — a club for those serving life sentence. From their very small earnings from their prison jobs, they have given thousands of dollars to charities.

Humility and remorse? As I write this, he has scores of people urging him to apply to have his sentence commuted. Yet, over and over, I have heard him express rending remorse for his actions and express fear of the impact a commutation would bring to Judy’s family to whom he caused so much pain.

Pastoral care? I once heard Baptist theologian Molly Marshall say, “The Baptist doctrine of the priesthood of every believer is not just that we each are priests to ourselves in coming directly to God. It means that I am your priest, and you are mine.” In that sense, Russell pastors me.

I once walked through the valley of the shadow of the death of all I thought I knew. It was the most I ever felt like a broken-down misfit Brennan Manning describes in his stirring spiritual autobiography The Ragamuffin Gospel. In three-hour visitation increments, Russell walked with me through my agonizing divorce and then a trauma triggered by my stumbling initial forays into dating.

When I nearly went under

Before our first and only date, I told a church-going woman I met online that despite all the pictures of her at church and Christian concerts and mission trips, I could tell from her social media political comments we were not compatible long term. However, I told her friends had encouraged me to get to know a variety of people. She agreed that a conversation to appreciate our political differences would be nice.

At the end of our date, she asked if I was sure I wasn’t interested in anything long term. I said I was. As I was driving home, the texts began. It devolved to drunk texts. She would not accept a polite “no thank you” for a second date. She started stalking and harassing me in ways that literally made me fear for my life.

One night, I had had two police cruisers in front of my house, lights glaring and neighbors staring. That was a good day, though, because the police officer said, “Sir, you don’t need to explain a thing. I could tell in 10 seconds, that lady is crazy.” The rest of the bureaucracy of filing charges was a nightmare. At a victim advocacy center, I had spilled my briefcase in the floor and collapsed in the floor sobbing after getting the third degree yet again from authorities not used to a 6-foot-2-inch 200-pound man being the victim of a female’s harassment.

“During this agonizing pain over relational abuse, I went to visit my pastor: A man convicted of murder, the worst kind of violence.”

During this agonizing pain over relational abuse, I went to visit my pastor: A man convicted of murder, the worst kind of violence. Notice I did not say “convicted murderer.” Russell used to be a murderer. He’s not anymore.

For the umpteenth time, I told Russell the new tragedies going on in my life. He shook his head in disbelief the whole time. When I finished, he gently said, “I’m so glad you’ve come to visit me. You help me realize how good I’ve got it. I get three meals a day and have armed guards protecting me.”

Now, you know you are in a horrible place in life when a person serving life without the possibility of parole doesn’t want to trade with you.

When I left the prison, I pulled over on the side of the road in a driving rain and sobbed as I beat the steering wheel.

‘A matter of geography’

I got that out of my system and felt myself filled with hope amidst the pain. That hope came from the other thing Russell said: “Brad, incarceration is just a matter of geography. We must make the most of where we are. You went on a date last week to the Knoxville Museum of Art. You likely would have preferred to go to the Louvre in Paris, but geography made that option unavailable, so you did what you could.”

He pointed out the open door to a playground for visiting children. “For the rest of my life I can never go farther than that first razor wire fence. There are outdoor plants, and there are indoor plants. But even an outdoor plant growing free by a stream can’t go anywhere else. I know most folks in the world out there will never see me as anything more than the worst decision I ever made. I know I’m not that person anymore. Still, I’m an indoor plant. But I’m going to be the best indoor plant I can be by making a difference in the lives of men who will leave here.”

“I know most folks in the world out there will never see me as anything more than the worst decision I ever made.”

Yeah, that gave me hope.

Looking at all the good Russell does, I also can engage in spiritual practices to transform my pain and to help me be the best fruit-bearing plant I can be, where I am. That is salvation.

Russell, the man who became a drug addict and organized the murder of his wife is now a gentle man who pours his life into helping others. His eyes are filled with peace and joy. His faith has helped him turn the worst manure of life into fertilizer, and his life bears good fruit. That is salvation.

Parallel lives

I once asked Russell if he could identify a specific point where our parallel lives forked — a moment that nudged him on a path toward drugs and murder. He shifted his gaze over my shoulder and stared into the past. I could see controlled pain in his eyes and the almost imperceptible Parkinson-like tremor of his head. Multiple times his lips tried to start.

Finally, he nodded slowly. Then, he told me his story.

It’s his story. All I’ll say is I’ve never done drugs or committed a murder. But neither have I had my adolescent pain squared or cubed. Given how poorly I have managed my own pain, I’m very fortunate I didn’t have the combination of experiences Russell described.

Yet, how do we respond to those who commit horrible acts? When I taught graduate counseling at a Christian university, I had a class watch the HBO documentary Child of Rage. It is a case study of a girl with reactive attachment disorder. As a toddler, Beth Thomas savagely tortured her infant brother. She was placed in intensive therapeutic foster care. The version of the film I showed included a supplement showing Beth as a well-adjusted adult who had become a nurse.

Twice in my career, I’ve had to step between students when their classroom debate got too heated. The graduate student discussion of this film was one of them.

The students were sitting in a U-shape. After the film, I asked, “If your child were a patient at Children’s Hospital and you found out Beth was the night nurse, would you leave your child alone with her?”

About half said no. A spokesperson for the naysayers said, “With someone like that, we never know when they might snap again.”

“If people can’t change, what the hell are we doing here in a counseling program?”

One of the males who said he would feel safe with his child in Beth’s care was sitting on the opposite side of the chasm between himself and the vocal naysayer. He got visibly angry, and an increasingly heated exchange began. Finally, the muscle-bound athlete yelled, “SHE WAS 5 YEARS OLD! IF PEOPLE CAN’T CHANGE, WHAT THE HELL ARE WE DOING HERE IN A COUNSELING PROGRAM?”

I stepped into the chasm and held my hands out like a traffic cop stopping traffic in both directions. We then talked about how family therapists talk about content and process of conflict.

In other words, we have what we argue about and how we do it. Clearly, there was irony in a discussion about violence becoming that heated. Still, the question was fair — especially for Christians. How much do we really believe in the power of redemption and transformation? And as a society, is justice more about punishment or reformation? From a sheer policy level, are we not more benefited by reformation?

My favorite hymn is often referred to as a children’s song. It makes more sense for adults to sing it.

(God’s) still working on me, to make me what I ought to be. Took (God) just a week to make the moon and stars, the Earth and the Sun and Jupiter and Mars. How loving and patient (God) must be, (God’s) still working on me.

Indeed, God is still working on me.

A tremendous guide on my journey is a redeemed and transformed convict. The world and I are much better off because he was not executed.

Like Jean Valjean in Les Miserables, Russell Freels has a number. Like Javert, we impoverish our lives even unto death when we reject others’ redemption and transformation. God calls us to better.

I rejoice that Chaplain Russell Freels has my number and, between our visits, calls me. Yea, though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death, my shepherds are with me. One of my pastors just happens to be in prison, where he is currently serving life — abundant life — to those whom he shepherds: prisoners and a ragamuffin Ph.D. family therapist alike.

Brad Bull

Brad Bull has served as a hospital chaplain, associate pastor and university professor, and he’s always trying to slip an Oxford comma past the BNG editor. He currently works as an online private practice family therapist in Tennessee and Virginia. His therapy and retreat services run via DrBradBull.com.