On the Sept. 22, 2017, edition of the radio show “This American Life,” journalist Zoe Chace was interviewing members of a group called Proud Boys. One of its co-founders describes it as a “pro-Western fraternal organization.”

On the Sept. 22, 2017, edition of the radio show “This American Life,” journalist Zoe Chace was interviewing members of a group called Proud Boys. One of its co-founders describes it as a “pro-Western fraternal organization.”

Chace quickly learned that a common grievance among the men she interviewed was that they feel marginalized. “Men are very marginalized,” one man said. “White male Christians are the most marginalized group in the United States.”

Chace asked them to explain why they felt this way. Here’s a sampling of the responses:

“We’re seeing more women getting degrees in universities. We’re seeing less boys graduate from college.”

“There’s no day for men besides Father’s Day, and who cares about that.”

“What about this compulsion to have women in action movies like Ghostbusters?”

When Chace asked what’s bad about women being cast as heroines in action movies, the man said, “That’s women saying they want to take over male roles. They want to be men.”

This is what’s called “persecution complex.” One dictionary defines it as “an irrational and obsessive feeling or fear that one is the object of collective hostility or ill-treatment on the part of others.” There are an unsettling number of examples.

This is the time of year when we start hearing another one: the “war on Christmas,” the supposed marginalization of the holiday of the majority religion in the U.S., and the unfair or unmerited recognition of other holidays. I actually had started to think the whole thing was a short wick that burned out. I was starting to think that some of the bloggers I follow were critiquing it every year just as low hanging fruit to go after. But if you go to the right places, you will see that it’s alive and well.

Of course, one of the most difficult factors in trying to converse about such things is that persecution complex is a real belief. These groups — with power, a majority, and/or a history of cultural dominance that has diminished — genuinely believe that this loss of influence is persecution.

The sociological factors at work are far more complicated than my treatment here. But there is one simple and relatively reliable way to distinguish real persecution or marginalization. It’s the factor that Chace asked of the Proud Boys that they couldn’t provide: personal examples.

If a person can provide multiple, real life, personal examples of how they or their community have fallen victim to abuse, harassment or exclusion, based on who they are and with little recourse and choice, then it’s likely the real deal. If generalities are all a person can give in response, or if they return to a few isolated incidents that are not systemic, then it is likely manufactured (and likely stoked by certain media outlets).

Ask Spanish-speaking immigrants, and many can tell you stories of being treated with disdain. Ask black citizens, and many can tell you stories of receiving unmerited suspicion and aggression. Ask LGBT citizens, and many can tell you stories of bullying, family abandonment, and violence. Ask Muslims (or Sikhs mistaken for Muslims) who wear something that looks Middle Eastern, and many can tell you stories of facing extra scrutiny and hostility.

And, as we’re learning anew, you can ask women, and many — way too many — can tell you stories of sexual harassment and assault.

Women have tried, through many different campaigns and social media hashtags, to help others understand how prevalent and debilitating it is. Women have recorded themselves walking down the street to show how often they’re cat-called and intimidated (I remember a female friend on Facebook posting such a video with the comment: “Every. Single. Day.”). Women have started nonprofits to try to fight it. Women have given TED Talks to try to explain why many don’t report, and what would help them report.

More recently, women started to tell their stories with the hashtag #metoo. In my social media feeds, I saw many men express shock and disbelief as female coworkers, friends, and family shared what has happened to them, many sharing their story for the first time. “I had no idea,” some said. “I never thought of it happening to you.”

A recent poll showed that more than half of U.S. women have experienced unwanted and inappropriate sexual advances from men, with almost a quarter of those cases including the workplace with a man who has influence over their work situation. This prompted a Forbes article to call it “a full-blown epidemic.”

It’s not that things don’t occasionally happen the other way. Men have been assaulted. Men have been falsely accused by women. These stories must be taken seriously as well, but the problem is that they can and have been used to flip the narrative and dismiss the larger patterns.

Personal stories are what often separate real abuse and neglect from that which is imagined, and we have to get this right. We have to get this right because people who are already voiceless are being re-silenced by those won’t believe them. We have to get this right because people who already feel powerless are further disarmed by not having someone to stand with them, and by having no one to go to except those who don’t want it to be true or can’t let it be true if they are to protect their interests.

We have to get this right because, alongside the trend of women finding the courage to come forward, we are also seeing a dangerous trend of men defending the behavior. In response to the allegations against U.S. Senate candidate Roy Moore, Alabama state auditor Jim Zeigler inexplicably used the biblical story of Joseph and Mary to defend how Moore “fell in love with one of the younger women.” Ohio Supreme Court Justice William O’Neill, in a since-deleted Facebook post that conflated consensual encounters and assault, called the current wave of abuse reporting a “national feeding frenzy.”

We cannot miss the gravity and urgency of this. This goes beyond the normal victim blaming and shaming, which continues to be a problem. Here we see perpetrators trying to flip the narrative and say that they are the victim. Here we see people coming up with more and more creative ways to say, “This is OK.”

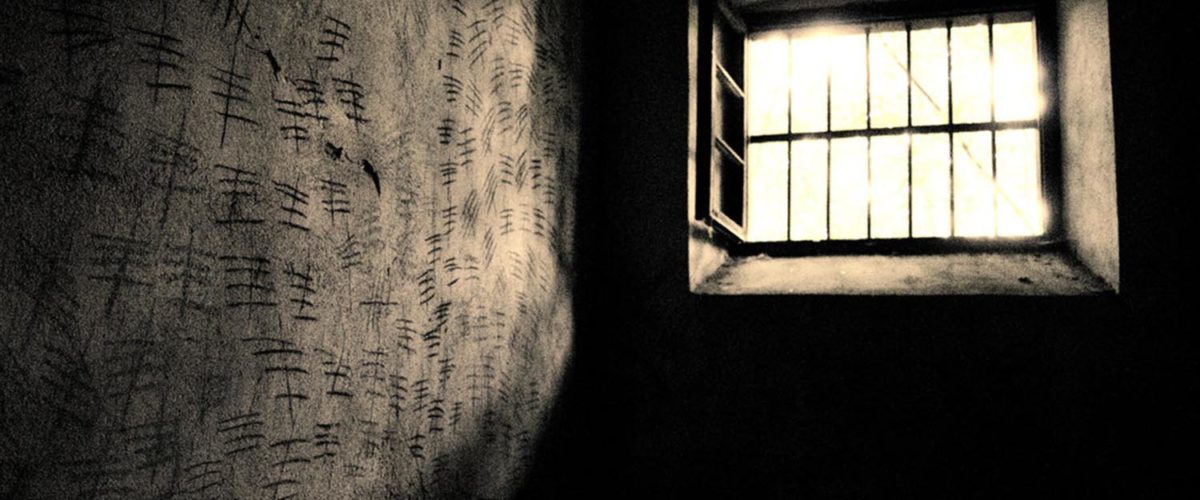

We have to get this right. The stories will tell us the truth. We must let the stories speak, no matter how hard they are to hear or no matter how much we dislike what they tell us about ourselves. We must not shove violence and neglect back behind closed doors where it has been for so many.

The gospel of God’s love for every person demands no less.