Once upon a time, I was a conservative. The last remnants of my conservatism died on Nov. 8, 2016, when Donald Trump was elected the 45th president of the United States of America, forever unmasking for me that whatever “conservatives” were trying to conserve was something in which I wanted no part.

In the years leading up to that fateful night, I’d found myself consistently less prone to self-identify as a conservative, but that was the Rubicon that, once crossed, brooked no return.

In the eight years since then, I’ve found myself moving steadily leftward in my political commitments, while also consistently deepening my commitments to orthodoxy in my theological outlook and commitments. These twin movements have complemented each other wonderfully.

Eugene R. Schlesinger

And while they probably could be disentangled — in that I am very well aware there are “conservatives” who are committed to orthodoxy — in my experience, it’s been my orthodox commitments that have motivated just about all my progressive turn.

My past as a conservative

Looking back at my past self, the reversal is almost comical. I was truly insufferable in my early 20s, particularly while attending seminary for my master of divinity degree.

Having undergone an evangelical conversion experience in my late teens, and having been brought by that experience into the heart of Southern Baptist evangelicalism, I took for granted the framework that to be a committed Christian meant to be a conservative. And, so, desirous of being a committed Christian, I set out to adopt the most conservative positions I could on any political or ethical question presented to me.

Seminary classmates and I would try to outdo each other in our hardline conservative positions.

Nazis come looking for Jews hidden in my attic? Well, the ninth commandment forbids lying, so I’d have to tell them the truth but then do all I could to stop them from reaching those hidden innocents. (Note that such would-be morally “heroic” positions were nothing more than fantasy, focused on a hypothetical situation from the past, with very little attention to the reality in which we lived with its injustices and needs for authentically gospel-informed Christian action.)

“The Bible” instructs us to preserve life? Well, that means there are no circumstances when one could legitimately withdraw care from a patient, including those in persistent vegetative states, kept alive solely by the ventilator. My long-suffering wife is a nurse, and my hardline commitments on these fronts especially horrified her, to the point where she put a friend from her work in charge of any end-of-life questions that might arise with her, for fear of what I’d do if the decisions fell to me.

“Looking back, I can affirm the impulse that drove me to take these positions: a desire to be faithfully Christian.”

Looking back, I can affirm the impulse that drove me to take these positions: a desire to be faithfully Christian. But I utterly repudiate so many of the places it took me and thank God I have lived in times where I wasn’t faced with making any of the sort of ethical decisions I took such glee in entertaining as hypothetical tests of fidelity.

That impulse to faithfulness was stultified by my own immaturity and failure to entertain a whole host of relevant questions, not least the identification of Christian fidelity with conservatism.

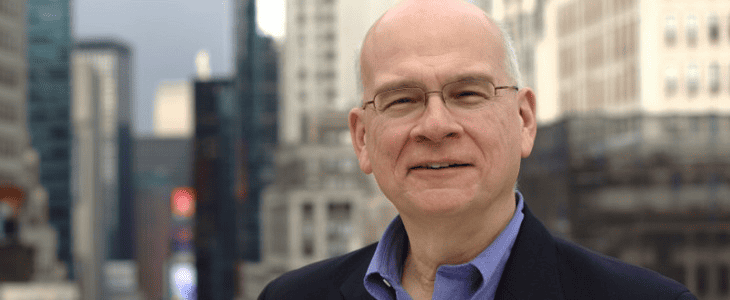

Tim Keller

Tim Keller

Fast forward a few years, when I came under the influence of the late Presbyterian minister Tim Keller. While I’m now worlds apart from Keller and those circles that looked to him for guidance, I also have no intention of disparaging him, much less now that he is among the faithful departed, but I did pick up a problematic habit from him, namely substituting “orthodox” for “conservative.”

Keller’s Redeemer Presbyterian Church is situated in the midst of Manhattan, and Keller, in his endeavor to winsomely mediate his Reformed evangelical faith to the denizens of this metropolis, sought ways to frame matters that would not lead to an immediate disengagement on the part of his audience.

So far as it goes, this is a pretty good pastoral and missional strategy. One should never hide who one truly is, nor soft-pedal the truth as they see it, but if you know that folks are going to get so hung up on terminology that they don’t even bother to consider the meaning you’re conveying, it behooves you and benefits all involved to use different language. People may still be turned off by and reject the message, but you want to give them the opportunity to get that far, rather than foreclosing the prospect of them even considering the message because you used a word that set off alarm bells. And in his Manhattan context, Keller recognized that describing his or his church’s theological positions as “conservative” would end most conversations about the faith before they got started.

This seemed like a grand strategy to me, and so I started using “orthodox” as a self-descriptor, rather than conservative. I did this particularly to hold in abeyance questions that I would have rather avoided, particularly on my (or the churches I served) positions on sexuality and gender.

“Looking back, I can recognize that the positions themselves are misogynistic and homophobic.”

I held the conservative viewpoints that men were supposed to lead women in the family and the church and that LGBTQ identities and expression were prohibited by Christian faithfulness and, if asked directly, I would answer honestly about them, but I didn’t want to invite those questions, and this was a way of postponing them. I didn’t hold these views out of any particular animus toward women or LGBTQ folks, but because I thought faithfulness to “the Bible” led to such positions. But looking back, I can recognize that the positions themselves are misogynistic and homophobic.

I should note here that this was my own equivocation, and that I’m not attributing it to Keller, per se. I’ve not listened to or read him in something like 12 years, so I don’t recall exactly what he said about this, and I certainly had no access to his interiority as he thought through these matters. What I did with the use “orthodox” instead of “conservative” strategy is my responsibility and not his.

Communion service at St. Timothy’s Anglican Church in Houston. (Photo from church website)

Switch to Anglicanism

Fast forward a bit more to when I moved from Southern Baptist evangelicalism to the Anglican tradition. My entry into Anglicanism was through the newly formed schismatic Anglican Church in North America, largely because it held to those conservative views I mentioned above (ACNA was formed explicitly because a cadre of conservative Episcopalians could not countenance remaining in communion with other Episcopalians who favored the affirmation of LGBTQ Christians and their full inclusion in all dimensions of the life of the church, such as marriage and ordained ministry), and because I was convinced Christian faithfulness demanded such LGBTQ exclusion of the church and of me.

Over time, my inhabiting of the Anglican tradition and my reading of Augustine’s anti-Donatist writings convinced me the schism and formation of the ACNA was unjustifiable, and my engagement with female priests and with LGBTQ Christians led me to reconsider my previous positions on sexuality and gender. (I talk about this journey in more depth in chapter three of my forthcoming book, Ruptured Bodies: A Theology of the Church Divided.) But that’s only tangentially related to this essay.

What I want to foreground is the way “conservative” Anglicanism (whether schismatics like the ACNA, the loyal opposition in my own Episcopal Church or conservatives in other Anglican provinces) tends to use “orthodox” to mean conservative positions on sexuality (gender too, sometimes, but it’s mainly about opposing gay marriage).

But here’s the thing: None of that is what “orthodoxy” means.

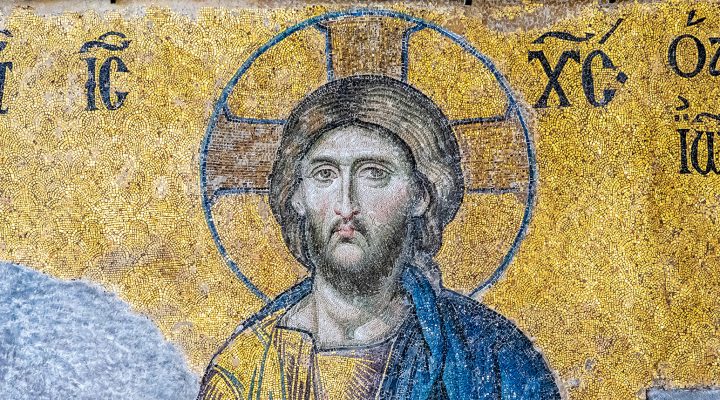

“To insert other matters, even true ones, even important ones, into our notion of orthodoxy actually downgrades orthodoxy.”

Orthodoxy was forged as the ecumenical councils discerned, clarified and defined the church’s faith on such matters as the divinity of the word and the Holy Spirit, giving rise to the doctrine of the Trinity; the union of Christ’s assumed humanity with his divine hypostasis; the necessity of divine grace and unbridgeable role of human freedom in salvation. To insert other matters, even true ones, even important ones, into our notion of orthodoxy actually downgrades orthodoxy, demoting matters vitally connected to our salvation and definitively taught by the church to the same status as more ancillary matters with lesser ecclesial standing.

It’s also ironic to conflate orthodoxy with conservatism, because as Rowan Williams demonstrates in his masterful study of Arius, the arch-heretic was driven to his positions due to a rather conservative outlook and commitments. Repeating positions from or the wisdom of the past is no guarantee of faithfulness in the present, particularly if it keeps us from addressing newly arisen questions.

Following my Anglican tradition’s Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral, which regards the Nicene Creed as the “sufficient statement of Christian faith,” I more or less restrict the meaning of orthodoxy to the Nicene faith (I’d add Chalcedon, as a further valid extension of Nicaea, but with the proviso that the ecumenical rapprochements with non-Chalcedonian churches are valid and to be celebrated). Within these parameters, the disagreements among Christians are intramural. Overly expansive definitions of orthodoxy obscure and subvert this.

Once more, the distinction between speculative theology and doctrinal teaching proves its utility. There are certain constraints with which we must operate if we would be Christian. Jesus as fully divine and fully human is not up for discussion. But within those constraints, as our friend Henri de Lubac alerted us, there’s quite a bit of latitude for exploration and argumentation. Foreclosing those avenues betrays a lack of confidence in the Holy Spirit’s guidance of the church in its sojourn and an impulse toward rigidity rather at odds with what we see in the life of Jesus of Nazareth.

“To use ‘orthodox’ when one means ‘conservative’ is rather to miss the point.”

So, to sum up, to use “orthodox” when one means “conservative” is rather to miss the point. To use it to mean particular moral positions, instead of the trinitarian, Christological and soteriological teachings of the councils, is to risk seriously downgrading and diluting orthodoxy.

Richard Hays

I’d drafted more or less all of the foregoing back in January, when I was toying with the idea of launching my SubStack. Then, about a month ago, a new book by Richard Hays was announced, making my reflections here relevant in a way I’d not quite anticipated.

Richard B. Hays and Chris Hays

For decades, Hays has been one of evangelical Christianity’s preeminent New Testament scholars, and his classic The Moral Vision of the New Testament was a go-to text for a fulsome defense of the traditional viewpoint that heterosexual marriage alone is an acceptable forum for sexual expression. Apparently, the new book The Widening of God’s Mercy articulates a shift in Hays’ views, one which affirms LGBTQ people and relationships.

I learned of this book on Twitter when I saw someone lamenting Hays’s fall into “heresy.”

I immediately tweeted something along the lines of what I’ve articulated above, though, as is unfortunately characteristic, I didn’t do so as generously as I probably should have (calling those who conflate “conservative” with “orthodox” “unserious”). This unleashed several concerned replies, worrying that this would surrender our ability to make moral claims or to insist that orthopraxy (right practice) is also crucial for Christian fidelity.

I don’t think that my claims here do anything of the sort, and that for a couple of reasons.

First, it’s perfectly possible for something to be true, to be important, to be something Christians believe or do, and not fall within the specific category of orthodoxy. I’m staking out my claims vis-à-vis gender and sexuality, and I think I believe as I do in concert with Scripture, with theological reasoning, with attention to the tradition.

“I also do not make the claim that holding these positions is orthodoxy and that denying them is heretical.”

I also do not make the claim that holding these positions is orthodoxy and that denying them is heretical. I hold these views because I think they’re correct, and good, and true, and vitally connected to my Christian faith, but that doesn’t make them orthodoxy. By the same token, I could be wrong in my judgment, but that doesn’t make me heretical. It might make me wrong or mean that I’m leading people astray (God forbid!), or something like that, but heresy has a particular meaning, and it’s not just “being wrong,” even seriously wrong.

Similarly, as I noted at the beginning of this essay, the Trump administration and the trajectory of the post-Trump Republican Party has convinced me I will never vote for a Republican again and that no one else should either. And I hold this position as an outgrowth of my Christian conviction. But it would be grossly inaccurate for me to say opposition to MAGA is orthodoxy and that a vote for the GOP is heretical. We need categories for things we think are true and good and even connected with fidelity that are, for all that, not “orthodoxy.”

Second, going back to the question of heresy, even if it is the case that Christian teaching is that LGBTQ affirmation is wrong and that gay sex is always and only sinful, or whatever else (I do not grant any of this. Some Christians teach this, but there are other Christians who teach otherwise. So “Christian teaching” is ambivalent and pluriform on this front.), it still wouldn’t be heretical, because there is no formally defined heresy that corresponds to this.

We’ve got lists of heresies, and it’s stuff like Arianism, Modalism, Pelagianism and so forth. If there were a formal declaration of heresy concerning such matters as gender and sexuality (and even the recent declaration from the Catholic Church’s Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith, Dignitatis Infinita, which does stake out positions against “gender ideology,” which some have pointed out don’t actually seem to correspond to anything in reality, does not amount to a formal exercise of definitive Catholic teaching), then the charge of heresy might stick. But unless and until such a formal declaration occurs, labeling such viewpoints — even if you think they’re wrong, bad and dangerous — as heresy is irresponsible and inaccurate.

I, for one, do not believe any such declaration ever will occur, because I believe the Holy Spirit will lead the church into all truth and prevent it from making definitive pronouncements that lead the faithful astray.

My point in these last few paragraphs is this: It’s fine for folks to disagree with the positions I’m staking out on gender and sexuality. They think I’m wrong. I think they’re wrong. But for such disagreements, we need a different framework than that of orthodoxy and heresy.

This column originally was published at the author’s Substack, Per Crucem in Deum and is republished here with permission.

Eugene R. Schlesinger is lecturer in the Department of Religious Studies at Santa Clara University. He earned a Ph.D. from Marquette University and is the author of four books, most recently Ruptured Bodies: A Theology of the ChurchDivided and Salvation in Henri de Lubac: Divine Grace, Human Nature, and the Mystery of the Cross.