Against all odds, Abram and Annie North rose up from slavery to own a home in Charlotte, N.C., that stabilized their family for generations. After Urban Renewal forced their descendants off their property, the most prominent church in town bought it at a bargain, and its value multiplied at least ninefold in just a couple of generations.

The story of the Norths’ home and its legacy within both their family and that church forms the core of Our Trespasses: White Churches and the Taking of American Neighborhoods, a new book by Greg Jarrell.

Greg Jarrell

The book traces the intersecting paths of the North family, once a solidifying force in Charlotte’s Brooklyn neighborhood, and First Baptist Church of Charlotte, which owns the land where the North home stood for generations. It’s a tale of the Norths’ aspiration, accomplishment and exasperation, as well as First Baptist’s theology, assumptions and power.

It’s also a tale repeated often across the country and through the decades. It echoes every time Black progress succumbs to white power. It repeats every time white meanings define the terms for Black existence. It multiplies every time white commercial value overwhelms Black community continuity.

Jarrell, a cultural organizer, musician and author who frequently writes for BNG, personalizes Our Trespasses by framing his story through the narrative of the North family’s rise, resilience and ultimate removal. Alongside, he focuses on First Baptist’s inability — or perhaps refusal — to acknowledge the consequences of its desire for place, prominence and power.

Our Trespasses spans more than 160 years, but its questions remain as relevant today as when they echoed through the decades. Most poignantly, they include:

- Why should white assumptions evaluate Black standards of living?

- What is the responsibility of the powerful, usually white people, to consider Black perspectives before making decisions that affect them both?

- How should a white institution, such as a church, consider the consequences of its actions when they impact neighbors?

- What is the obligation today of whites — who did not make race-involved decisions but still benefit from those decisions — to Black neighbors who continue to suffer the consequences of white power exercised upon their forebears?

- How does gentrification today mirror previous real estate practices and policies that exploited Blacks?

The questions haunt the tale, which Jarrell tells in three compelling acts.

Our Trespasses begins with Abram and Annie North and tells how a Black family in the South progressed from enslavement to home-ownership and the place of that family and their home in the community. Meanwhile, it also tracks the development of First Baptist Church, a congregation descended from enslavers.

Next, Jarrell introduces the havoc wreaked by Urban Renewal — how the North family and all their neighbors in Brooklyn were driven from their homes. Alongside their anguish, Charlotte’s Redevelopment Commission waved a temptation First Baptist chose not to ignore — relocation property near downtown, including the historic North homeplace, at an unreasonably low price.

And then the book examines the 60-year period from the church’s relocation to the present. It traces the economic damage inflicted on the North family and their former Brooklyn neighbors, but it also outlines the cultural and moral damage Urban Renewal inflicted on the white congregation.

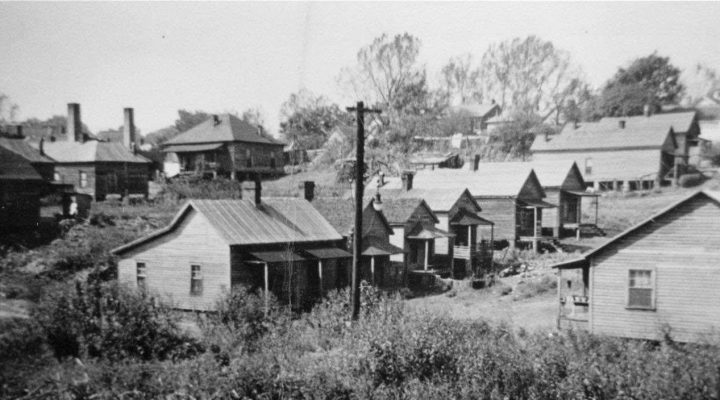

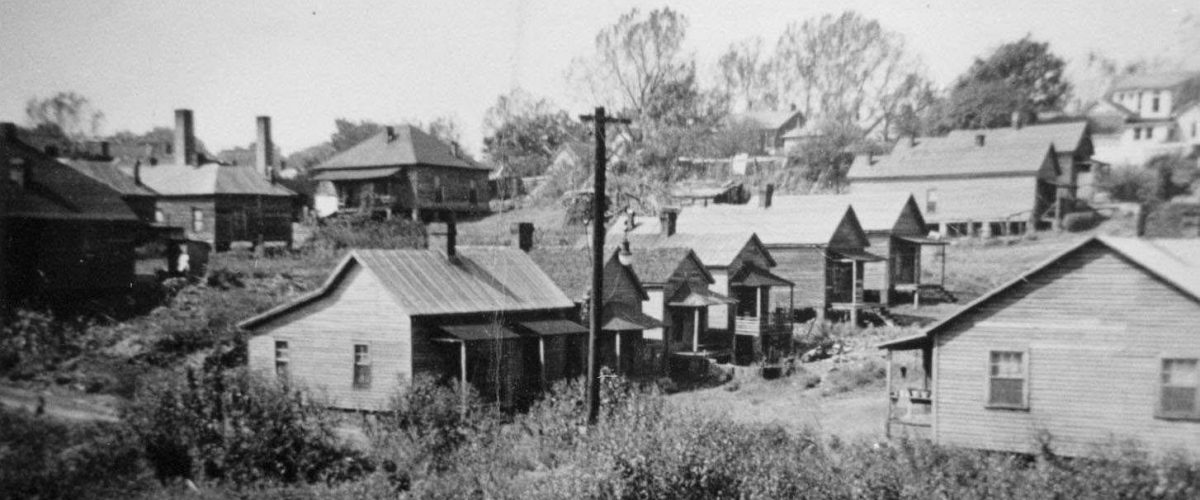

Brooklyn business district on South Brevard Street, with Mecklenburg Investment Company Building in foreground, Grace AME Zion church in background. (Photo courtesy of the Robinson-Spangler Carolina Room, Charlotte Mecklenburg Library)

Although Urban Renewal ended about 50 years ago, the dynamics at work on the Norths, on Brooklyn and on FBC Charlotte persist, particularly regarding urban poverty, Jarrell says.

“What happened in Charlotte maps well onto what happened (with Urban Renewal) around the country, and continues to happen in changing forms that lead to the same results,” he notes. “Yesterday’s displacement by Urban Renewal is today’s displacement by gentrification.”

In an interview, Jarrell said he hopes readers take away at least two lessons from Our Trespasses.

“Part of what I want folks to do is recognize this is not a Charlotte story,” he said. “As important as the details are for me, this will provide an example of the kind of work that needs to be done all over the country.

“I also want folks to know we still live inside this story. What I’ve written is recognizable across the country, in places as diverse as Waco and San Francisco. The story arc has been buried deep inside of us as part of our Baptist formation and as part of the formation that is whiteness.”

Christians who have benefited from whiteness are responsible for figuring out what to do about those benefits, Jarrell added.

“It’s important to note this stuff didn’t happen that long ago.”

“It’s important to note this stuff didn’t happen that long ago. Sixty years in the course of institutional lives is not very long,” he said. “It’s not simple but not difficult to track what could have been. It’s reasonable to suggest public and private institutions should join together to pay some kind of reparations for what can be calculated. Our lives are not monetary, but they are impacted by money.”

And churches should dig into their pasts with open eyes and open hearts, he added.

And churches should dig into their pasts with open eyes and open hearts, he added.

“Part of the work that has to be done in our congregations is to understand the stories of our places and to be responsible to the people who came before us,” he stressed.

“Rather than suggesting a program of restitution or repair, I would suggest if you studied your place and were able to develop solidarity relationships with people who came before you, that might open up imaginative possibilities with the descendants of those who went before. If you ignore the past, you snuff out those possibilities.”

Robert Welch, pastor of First Baptist Charlotte when the book was researched and now pastor of Legacy Hills Church in Celina, Texas, declined to comment. Rob Wilton, newly arrived pastor of First Baptist Charlotte, did not respond to requests for comment about Our Trespasses.

Related articles:

What to do if you unearth a history of slavery in your church, college or institution?

Dig deeper when looking for your church’s racist or anti-racist history, Gardner advises