Former Southern Baptist statesman Paige Patterson claimed a religious liberty defense, while denying the bulk of allegations in a lawsuit over his handling of sex abuse claims, in an answer filed Aug. 26 in federal court.

Patterson, widely acknowledged as co-founder of a movement in the late 20th century to move the Southern Baptist Convention sharply to the right, denied that Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Fort Worth, Texas, was an unsafe place for women when he served as president there from 2003 until his termination last year at age 76.

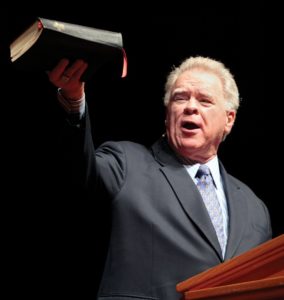

Paige Patterson

He also disputed accounts of a private meeting with a former female student identified in court documents as Jane Roe, while at the same time claiming any information shared in the conversation is protected by the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.

In a lawsuit filed in May in U.S District Court in Sherman, Texas, an Alabama woman using a pseudonym claimed she was stalked and later sexually assaulted multiple times by a male student employed on campus as a plumber.

She said Patterson refused to believe her stories until he had a chance to – in his own words – “break her down.” She said in an August 2015 meeting also attended by her mother, Patterson defended the decision to enroll an alleged sexual predator, grilled her with questions about whether their sex was consensual and told her rape might in the long run be a “good thing” because the right man to be her husband would not care if she is a virgin.

Patterson gave a blanket denial to those allegations, claiming that any harm done to the woman resulted from actions of someone other than him. Trying to hold him liable for conduct delegated to others under the governing documents of a religious body like a seminary, he said, would violate the First Amendment.

Patterson, who before leading Southwestern Seminary served nine years as president of Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary in Wake Forest, North Carolina, got swept up in last year’s #MeToo movement protesting the abuse of women by powerful men when old sermon comments counseling a battered wife to stay with her abusive husband and sexually objectifying a teenage girl resurfaced on the Internet.

That opened the door to new allegations that he mishandled rape reports at both Southeastern and Southwestern seminaries by blaming, shaming and bullying female accusers. The controversy led to his firing last May by the executive committee of Southwestern Seminary’s board of trustees and cancellation of two addresses Patterson was scheduled to make at the 2018 SBC annual meeting in Dallas.

This year’s SBC annual meeting in Birmingham, Alabama, focused on allegations of widespread abuse and coverup in Southern Baptist churches and institutions accumulated in a series of investigative newspaper reports by the Houston Chronicle and San Antonio Express-News.

The most recent installment, published just last week, found a number of old videos and documents detailing Patterson’s alleged defense of a young pastor protégé accused of sexual misconduct by dozens of women in the 1980s.

In his legal response, Patterson disputed characterization of his behavior as “extreme and outrageous.” He also denied sharing false information about Jane Roe for purposes of distribution.

Patterson also claimed Roe’s allegations of negligence and gross negligence against him are time-barred by a two-year statute of limitations, rather than a five-year window to sue someone for sexual assault.

He further argued that allowing a secular court to judge whether it was reasonable for the seminary to enroll the alleged perpetrator would create “an excessive entanglement with religion in violation of the First Amendment.”

Patterson denied causing any of the injuries or damages claimed by Roe, saying they were the result of unforeseeable circumstances unrelated to him. He also denied liability for injuries resulting from “pre-existing and/or unrelated medical or mental conditions.”

In addition to Patterson as an individual, the lawsuit names Southwestern Seminary as a defendant. In their response, lawyers representing the seminary denied responsibility, saying any offenses or omissions by Patterson were committed outside his scope as a seminary employee.

In his answer, Patterson said similarly he “is not personally liable for the liability of SWBTS.”

Previous story: