Mental health professionals and ministers working together can help change the social narratives that justify racism and oppression in the United States, an online panel of therapists and clergy said Aug. 28.

But they also must possess that awareness and be willing to exercise that leadership to contribute to systemic change.

Nathaniel Strenger

“Those of us in socially oriented professions wield enormous influence,” Nathaniel Strenger, a psychologist with The Center for Integrative Counseling and Psychology in Dallas, said in opening the Zoom discussion titled “Understanding racism and anti-racism: Lessons learned from therapy and ministry that can bridge racial divides.”

“Racism can begin in our offices, but so can ending it,” Strenger said.

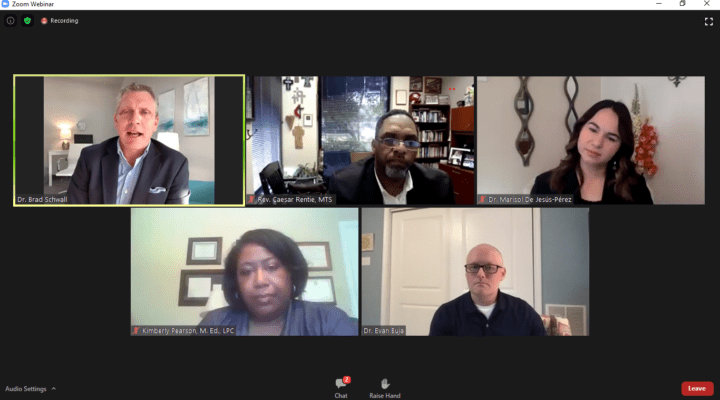

Moderated by Brad Schwall, president and CEO of The Center, which hosted the event, the conversation ranged from the impact of racism on individuals and communities to practical steps to help clients and community members process the anger and shame caused by systemic oppression.

Caesar Rentie

Panelists also shared how racism reveals itself within their ministries and practices.

“How has race impacted my work? It always has,” said panelist Caesar Rentie, vice president for pastoral services at Methodist Health System in Dallas.

As a chaplain, Rentie said he sees how racism plays out in the lives of patients and staff. It also affects the way he, as a Black man, interacts with others. “I realize that (racism) impacts me and impacts my ability to be present for those who come to the hospital seeking our help. Being aware of race itself is a daily task.”

The COVID-19 pandemic, he added, mirrors the Black experience in America. Between hiding true identity behind masks and never knowing who has the virus, the coronavirus outbreak allows people to be their true selves only at home. That’s how African Americans always have existed, he said.

“We are all living this Black experience in America where you have to live two lives.”

The heightened stress from the pandemic and from protests over police brutality have enabled some clients to more readily see the deeper sources of their anger and anxiety, said panelist Kimberly Pearson, a staff therapist at The Center who practices at local churches in communities populated mostly by people of color.

Previously, clients usually cited work or family troubles for their depression or anxiety. Current events reveal how emotional health is denigrated by social, economic and legal discrimination, she said. “Now with these external events, that trauma is more apparent. The real work can be done. Now we can get to the core of some of these things … so clients can truly heal.”

The symptoms of that deeper issue include anger and shame. Pearson said she practices in church settings because they are traditionally considered safe spaces in Black communities. “In my experience, church is a place of healing and refuge.”

Kimberly Pearson

The emotional impact of systemic racism isn’t limited to people of color, said panelist Marisol De Jesús-Pérez, a staff psychologist at The Center.

Some Black clients have experienced feelings of empowerment during this period of racial protest, while white clients have nervously admitted to feelings of shame.

Hispanics have remained largely disconnected because they are simply trying to survive, added De Jesús-Pérez, an ordained minister in the Free Methodist Church. “These events have made very clear the need for changing our narratives. As a country we have had narratives that justify violence and slavery.”

Slavery, she added, remains operative in the forms of higher incarceration rates for Blacks and in lower numbers of African Americans in high-paying jobs. Trying to justify such disparities makes everyone sick. “We have been having this conversation forever,” she said.

Marisol De Jesús-Pérez

Rentie added that he sees the disparity at play in the way former President Barack Obama, a dedicated family man, is denigrated, while President Donald Trump, who is beset by scandal, is celebrated.

“It’s a double standard I have had to live my life by,” Rentie explained. “That’s the experience of all the Black people I know.”

Despite the benefits of therapy, the panelists noted that mental health services can be a hard sell for many Blacks concerned about being further stigmatized.

“Not only am I Black, but I’m crazy,” Rentie said the reasoning goes. “When someone comes and says, why are African-Americans so resistant to mental health (treatment)? It’s because it’s one more label.”

Another theme that emerged in the discussion was the importance of not rushing to reconciliation.

Conversations about building bridges between people of color and dominant white culture are necessary but must be preceded by a process of lamentation and amends, participants said.

“If we tap into the narrative of reconciliation without restoring justice, we are doing more harm,” De Jesús-Pérez said.

Likewise with clients, she explained, it’s unwise to try to bury difficult emotions connected to life-long discrimination. “So, I explore the anger and I explore the shame.”

Rentie added that a process of lamentation communicates empathy with the oppressed, and empathy opens the door to healing love. “Then we can begin to have a real discussion of what we are afraid of.”