Correction: This story was updated after posting to correct an error in the sixth paragraph.

By Bob Allen

Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary convened a panel Sept. 11 for a 50-year retrospective on a controversy that many believe planted seeds for the so-called “conservative resurgence” in the Southern Baptist Convention beginning in 1979.

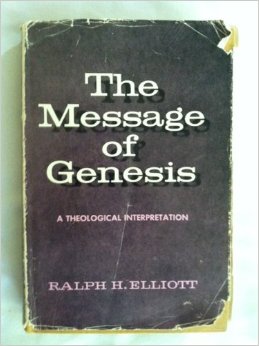

Jason Allen, president of the SBC seminary in Kansas City, Mo., described uproar over Ralph Elliott’s 1961 Broadman Press book The Message of Genesis as one of the top-five controversies in the history of the nation’s second-largest faith group founded in 1845.

“Fifty years isn’t very long when you consider the vast expanse of history, but it is long enough to reflect and to be able to gauge what has happened and what we can learn from it,” Allen said.

“Fifty years isn’t very long when you consider the vast expanse of history, but it is long enough to reflect and to be able to gauge what has happened and what we can learn from it,” Allen said.

Allen traced roots of the conflict to the founding of Midwestern Seminary established by vote of the Southern Baptist Convention in 1957.

“You can’t think of the founding of this seminary without looking eastward to Southern Seminary in Louisville,” he said. “The reason I say that is because almost the exact same time this seminary was founded there was a massive controversy in Louisville that led to dismissal of 13 professors and a dramatic relocation from there. Many of those professors came here. Many of those professors went to Southeastern Seminary, and the theological liberalism that was at Southern — and in some ways was at all our seminaries — made a dramatic spread in light of that controversy.”

Ralph Elliott was the first member elected to join Midwestern’s first faculty as professor of Old Testament and Hebrew. After the move, he completed the book he started at Southern Seminary, in which he took a symbolic rather than literal approach to Genesis by stressing its “theological and religious purpose.”

Critics charged the work denied the historicity of the first 11 chapters of Genesis. K. Owen White, pastor of First Baptist Church in Houston, responded with a widely distributed essay titled “Death in the Pot,” based on 2 Kings, 4:40, which labeled Elliott’s book “liberalism pure and simple.”

Critics charged the work denied the historicity of the first 11 chapters of Genesis. K. Owen White, pastor of First Baptist Church in Houston, responded with a widely distributed essay titled “Death in the Pot,” based on 2 Kings, 4:40, which labeled Elliott’s book “liberalism pure and simple.”

Fearing the controversy would split the SBC, the 1962 convention voted to form a special committee to study the 1925 Baptist Faith and Message and bring a report the following year. The committee revised the confession of faith adopted during the fundamentalist-modernist controversy of the 1920s with adjustments that came to be known as the Baptist Faith and Message of 1963.

Midwestern’s trustees eventually fired Elliott, not for heresy, but for insubordination after he refused a request not to offer his controversial book for republication.

Greg Wills, dean of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary’s school of theology, cited “extreme challenges” to traditional beliefs that drove the controversy.

The “historical-critical” or “higher criticism” method of Bible interpretation that took root in the 19th century, he said, “was attempting to put the Bible under the rational scrutiny of a historical method, a scientific method.”

Meanwhile, he said, moral objections to the Bible were “raised very powerfully” in questions like, “Did God really command people to genocide, this kind of thing, wiping out the Amalekites?”

Finally, he said, there was “the intense challenge presented by evolution in particular.”

“All of these things presented intense pressure upon Christians to change their view of inspiration,” Wills said. “We need to have a view of inspiration that will allow us to keep our confidence in the scriptures as a religious document but at the same time allows us to accept the claims that are coming out of historical science and moral science and evolutionary science.”

“This is liberalism, and this is the main threat to historic faith of the church over the last 150 years,” Wills said. “So it’s not surprising that most of our controversies — in fact our most intense controversies — have been expressions of, on the one hand, the people and most of the pastors seeking to retain their full confidence in the inspiration and the inerrancy of the Bible, and on the other hand, some of our more progressive leaders — mostly professors — pushing for a more open, more progressive tolerance of these new ideas.”

John Mark Yeats, pastor of Normandale Baptist Church in Fort Worth, Texas, and a former church history faculty member at Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, said Elliott saw no contradiction between affirming the moral teaching of the Bible but not its historical accuracy.

“What I think is even more shocking is that as Elliott writes later reflecting on the controversy, he says this was consistent among all of our schools,” Yeats said. “This is what all departments were teaching.”

In his 1992 book The Genesis Controversy Elliott wrote of “doublespeak,” the tendency by professors to speak clearly within a critical tradition when they were with other scholars, but in church and convention settings to sound as if they agreed with the least-educated person present.

While presumably meant to keep everyone happy, the concept prompted conservatives to scour out-of-print books and secretly record seminary classroom lectures seeking to root out heresy during the height of the SBC controversy in the 1980s.

Wills said he doesn’t know of a single professor at an SBC seminary who objected to the use of methods of higher criticism during the era. “If they had all communicated what they truly believed, all the seminaries would have been shut down within one year,” he said.

Michael McMullen, professor of church history at Midwestern, said the SBC publishing house didn’t learn its final lesson from the Elliott controversy, evidenced by a later skirmish that forced the then-Baptist Sunday School Board to withdraw and reissue Volume 1 of the Broadman Bible Commentary in 1969.

“The Genesis one,” Wills interjected. “The Exodus [volume] was just as bad; Exodus [was] written by a professor here.”

The author of the Exodus commentary was Roy Honeycutt, who went on to serve as president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary from 1982 until 1993 and died in 2004.