Jennifer Ikoma-Motzko, a Japanese-American mom and Baptist minister, says an unusual weariness crept over her this summer when news broke of the forced separation of immigrant children from their parents at the U.S.-Mexican border.

“As the images and stories started pouring into my newsfeed, I realized I was shutting down because I’m imagining what it must be like to be separated from my kids,” said Ikoma-Motzko, who formerly served as senior minister at Japanese Baptist Church in Seattle.

But the anguish created by Donald Trump’s “zero-tolerance” policy – rescinded after mass outcries in June –has been pushing other buttons for Ikoma-Motzko, as well.

Jennifer Ikoma-Motzko

“I think it’s because, subconsciously, I’m making a connection to what happened to my family.”

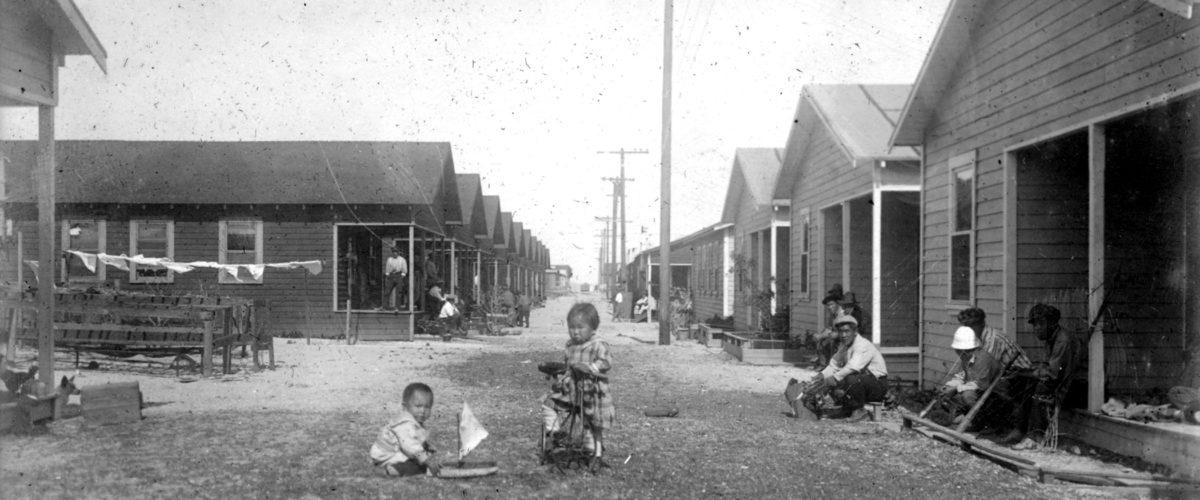

What happened to her family was one of the darkest chapters in U.S. history when close to 130,000 Americans with Japanese ancestry, including children, were forced into internment camps during World War II.

The parallels between the two situations, Ikoma-Motzko said, are striking. Both policies were carried out by executive order, both claimed to enhance national security and both dehumanized those who were targeted.

Which raises troubling questions for people of faith in the United States, she said.

The answer, she said, is giving loyalty to Christ and the kingdom ahead of governments.

“If people consider themselves Christians, then their citizenship expands beyond geopolitical boundaries.”

Ikomo-Motzko, who recently moved to Minnesota with her family, spoke with Baptist News Global about what it means to be disciples of Jesus in a zero-tolerance era. She also shared how the wartime experiences of her relatives and former church members shaped her ministry. Here are her comments, edited for clarity.

Before we jump in, how did some of your ancestors become Baptists?

I’m a fourth generation Christian in my family and fourth generation Japanese-American. I have some Buddhist family members, and I am not clear on when some of my relatives became Christians. But I did grow up in a Baptist church. My parents got married and dedicated me and a younger brother at Northshore Baptist Church in Chicago. When I decided to get ordained, I was interning at an American Baptist church. So, when I felt a calling to become a pastor, that’s where I was ordained. Then I applied to become the senior pastor at Japanese Baptist Church in Seattle.

You had church members there who had survived World War II, both in the U.S. and in Japan. How did they manage to navigate their differences after the war?

Going through World War II was such a definitive chapter for some of those at JBC. But there wasn’t a sense that the people who were interned were more important than the people who had the atomic bomb dropped on them. There’s also a shared mentality of being told you can’t be American, you look like the enemy so you can’t be loyal. They knew that wasn’t true, but that’s what people kept telling them.

How formative were the camps in their lives?

Some of the very first Japanese-Americans to experience this injustice were members of this church. Some of the survivors were very little at the time. We have people at JBC who were born in the camps. After experiencing that and returning from the camps and trying to rebuild their lives, they found themselves sitting next to someone who is a Hiroshima survivor. And maybe their brother fought in the 442nd (a U.S. Army regiment made up of Japanese-Americans who fought in Europe).

How were your own relatives impacted?

My grandmother, my mom’s mom, saw her dad being taken away before the war when the FBI started targeting influential people they thought needed to be detained. My great grandfather was one of those men. So, the FBI knocked on their door and they took him away, leaving my grandmother and her siblings at home, parentless. He was the only parent in the home, and those children were just left alone.

What happened to them once the war started?

My grandmother and her siblings had to figure out how to get to the assembly sites and actually went to the camps without their father, who was in a different camp.

That sounds very much like what’s happened this summer at the border.

Yes. People said about the Japanese-Americans: “What could we do? It was wartime. It was legal. The government said it was necessary to protect our borders, to protect the West Coast. We needed to do this to protect America, and it was completely legal because the president signed the executive order.” That’s horrifying to hear that again in the news today.

How did those issues play out in your family?

My parents were not born yet during World War II. They are a generation raised by parents who never talked about the war, almost like it never happened. My parents grew up not hearing about the internments. Their grandparents just wanted to rebuild their lives and to have their kids be as American as possible so none of this could happen to them. My parents grew up speaking only English.

When did the war and the internments begin to be talked about?

My parents grew up and had kids and suddenly my grandparents realized they had grandchildren who don’t know about this history or what’s happened. Suddenly they felt the need to share this history so that it’s not forgotten. In my family it was especially my mom’s mom who started talking about what happened during World War II.

In what ways did she share that history?

She would give me children’s books about the internment experience. Grandma could bake a mean apple pie, but she was also an advocate for social justice who organized letter-writing campaigns to make the government apologize. And she testified before Congress. She was very vocal and wanted to be sure the country knew, and she especially wanted her grandchildren to know. She wanted no one to forget.

How has all of this shaped you and your ministry?

My grandma had a very strong identity as a Christian and she was in many ways a role model for me. She presented a very holistic picture of what it meant to be a Christian. She modeled personal piety and how your life should look more like Christ’s life every day. She also had a calling to serve the collective good and to fight for justice because all people are created in God’s image. I’ve definitely taken that into ministry with me.

Related coverage:

Baptist uses literacy work to promote love, oppose ‘zero-tolerance’

‘Zero-tolerance’ support thrusts Sessions into Methodist justice process

Opposition to Trump ‘zero-tolerance’ must go grassroots, organizers say