Research once again shows that confidence in organized religion remains at all-time lows.

But what the numbers don’t reveal is the toll that the erosion of reputation and relevance has had on churches and ministers throughout the decline. It’s often described as an astonishing and disturbing experience.

“In the early part of my ministry you could go up to a door and introduce yourself as a pastor and you would get a cordial reception,” said Charles Updike, pastor emeritus at First Baptist Church in Glendale, California.

“Today in some neighborhoods of LA you’re asked, ‘why are you coming here?’ or ‘why do you want to pray for me?’” said Updike, who was ordained in 1973.

But it’s not just Los Angeles. A recent Gallup survey reports that respect for churches and other religious organizations has reached “another low point” across the U.S.

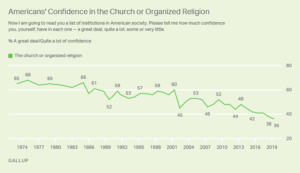

“Americans’ confidence in the church or organized religion continues to erode,” Gallup said in a summary of the survey conducted earlier this year. Only 36 percent of respondents reported having either “a great deal” or “quite a lot’ of confidence in faith groups.

The research also looked at other institutions, finding the church in sixth place behind the military, small business, police, the presidency and the U.S. Supreme Court.

That wasn’t always the case. Confidence in churches and other religious institutions reigned supreme from 1973 to 1985. The televangelist scandals of the 1980s and the Catholic sexual abuse revelations of the early 2000s eroded that trust, Gallup said.

“Since then, in 2018 and 2019, Americans’ confidence in religion has been below the 40% mark.”

‘We have blurred the lines’

But that shift in attitudes wasn’t limited to those outside the church, said Danny West, professor of preaching and pastoral studies at the Gardner-Webb University School of Divinity and previously a senior pastor ordained in 1979.

Danny West

West recalled a church he led in the 1990s where attendance began to dip as members had competing priorities, including youth travel sports teams, on Sunday mornings.

“They were much more affluent and had lots of opportunities to be gone – and they were,” he added. “That was a wake-up call to me that church was not as important.”

The trend stood in stark contrast to his own experiences growing up and even to the earlier part of his career.

“It was then I began to notice church was not as important to people as I imagined it would have been.”

Televangelist and sexual abuse scandals clearly have taken their toll, West said, but so did the “Baptist wars” within the Southern Baptist Convention and the church effort to cater to an ever-pluralistic society.

Changes in worship, embracing politics and watering down theology and Christology have served only to confuse a wider population that needs a clear, hopeful message from the church, he said.

“We have blurred the lines between the sacred and the secular virtually to the point where the two are indistinguishable,” he said.

Legalism hasn’t helped, either.

“Too often we worship the god of the (church) constitution and bylaws.”

‘The culture is more skeptical’

Grief was often present as clergy and church status diminished, said Ronald “Dee” Vaughan, who served as a chaplain and a youth minister before becoming a senior pastor in 1982.

Growing up in the church and attending seminary in the era he did provided no warning that change was coming.

“One thing I remember from my early days was the assumption of credibility” that came with ministry, said Vaughan, the pastor at St. Andrews Baptist Church in Columbia, South Carolina.

Ronald “Dee” Vaughan

“There was a basic feeling that you are a pretty good person if you are in ministry, that you are probably someone working for the good in people’s lives.”

That meant most first-time encounters with people were positive.

“While that is still sometimes true, I run into more situations now where the response is neutral or negative,” he said.

In part, the dim view people have of churches, and by extension ministers, is reflective of attitudes Americans have toward institutions in general.

“The culture is more skeptical of anyone who has any kind of authority,” he said. “There is an overall skepticism in our culture.”

‘More and more marginalized’

Yet, many Christians are in denial about those changes, said Robert Creech, professor of pastoral leadership at Baylor University’s George W. Truett Theological Seminary in Waco, Texas.

Creech previously served as a lead pastor after finishing seminary in 1976.

Throughout the decline some clergy and congregations have perceived themselves as a mistreated majority rather than an increasingly marginalized minority.

Robert Creech

“We think we have a lot larger market share of people’s loyalty and confidence than we really do,” he said.

Suspecting that was the case in the late 1980s, Creech led a group from his Houston congregation to ask local residents about the churches in their neighborhood. The results were startling.

“We might as well have been Buddhist temples – we were not on their radar,” Creech recalled. “Had I said ‘name three donut shops’ they would have done better. We were not in their field of vision.”

Nowadays, seminarians are being prepared for these realities, he said. This includes learning how to handle sexual abuse allegations and how be a minister in a society that doesn’t trust organized religion.

“It doesn’t mean you’re a trusted person, anymore,” he said. “You have to earn that confidence in the congregation as well as in the community.”

‘I can handle it myself’

Charles Updike

But even that is hard to do in a society that’s become increasingly unaware of the church, Updike said.

He witnessed that development as computers, the internet and social media dominated not only American culture, but church culture.

Meanwhile, trends such as destination weddings and the ability to parse scripture-without-context from apps has led many Americans to seek to do the tasks once associated with ministers and churches – such as weddings and funerals.

“What I’ve seen is a shift away from letting church handle it or letting clergy handle it to ‘I can handle it myself,’” Updike said.