I grew up in the shadow of the Christian Broadcasting Network. I even met Pat Robertson a few times. In high school, I acted in a commercial for The Family Channel. Some of the money Pat Robertson made from its sale paid for my full scholarship to Regent University.

While at Regent, I worked as a freelancer for CBN and I remember overhearing two lighting technicians talking about Pat Robertson: “He listens to the wrong people,” and “Anyone can get his ear,” and “He just goes with the last thing he hears.”

After sifting through several decades of my “neighbor’s” trash, I think they were right. Often the wrong person to whom Pat Robertson listened was himself.

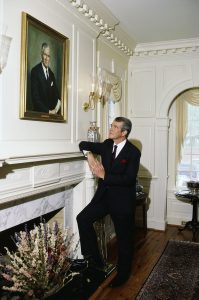

Pat Robertson looks at a portrait of his father in his home in Washington, DC.. Robertson was the founder of the Christian Broadcasting Network and tried to run for president of the United States in 1987. (Photo by © Shepard Sherbell/CORBIS SABA/Corbis via Getty Images)

Marion Gordon “Pat” Robertson had a knack for being in the right place at the right time. Born into a life of privilege, his father, Absalom Willis Robertson, was a senator from Virginia. Willis was what would become known in political parlance as a “Dixiecrat.” Anti-New Deal and pro-Jim Crow, Willis Robertson peppered his political diatribes with Scripture. He was against Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty because, “Jesus said, ‘The poor ye shall always have with you!”

The apple didn’t fall far from the tree.

Raised Southern Baptist

Pat Robertson was raised Southern Baptist, and both of his grandfathers were SBC pastors. One great-grandfather was the first corresponding secretary of the SBC Home Mission Board. Robertson said his father “used to tell me stories about the persecution of Baptists in this country. He did not like government intervention in the affairs of people and I think he’s passed that on to me.”

One intervention Pat Robertson didn’t mind was his father pulling strings to keep him out of harm’s way during the Korean War, when the younger Robertson served as a Marine — a fact that would come back to haunt him during his 1988 presidential campaign when he claimed to be a combat veteran.

After the war, Robertson graduated from Yale Law School and married a Catholic nursing student he met at Yale named Adelia “Dede” Elmer. After failing the bar exam, Robertson dabbled in politics and lost money in business. Aimless and depressed, he decided to become a minister.

In his autobiography, Shout It from the Housetops, Robertson recounts his conversation with Dede: “You know, I really feel God wants me to go into the ministry.” She replied, “I guess if you’re going to think seriously about going in the ministry, we ought to start going to church and find out what it’s all about.” Robertson hadn’t attended church since he was a teenager in Lexington, Va. After sampling a few churches in New York, he went home to Virginia to tell his mother his good news.

His mother, Gladys, was the primary spiritual influence on his life. Those who knew her described her as a “strange and remote” woman who “prayed and read the Bible almost ceaselessly.” She had been sending her son tracts and “preachy letters” for years. Gladys asked him bluntly: “But how can you go into the ministry until you know Jesus Christ?”

In 1957, Robertson’s mother arranged for him to meet the missionary Cornelius Vanderbreggen, who had a penchant for tying Scripture to real-world events. Vanderbreggen impressed Pat by taking him to a fancy restaurant where the waiters wore tuxedos. “God is generous, not stingy. He wants you to have the best,” said the missionary.

There Vanderbreggen distributed his tracts to eager waitstaff and read aloud from a huge Bible. After some coaching from Vanderbreggen, Robertson admitted aloud that Jesus had died for the world’s sins and his own. With this confession, Robertson says he finally understood God’s “love for him poured out through Jesus Christ.”

Southern Baptist minister, broadcaster and presidential hopeful Pat Robertson on set of The 700 Club with Ben Kinchlow and Danuta Soderman in August 1986 in Virginia Beach, Virginia. (Photo by Ed Lallo/Getty Images)

Charisma and TV

Robertson returned north and attended the nondenominational New York Theological Seminary, which may explain why he never espoused many traditional Baptist beliefs. Eugene Peterson, best known for his Bible paraphrase, The Message, attended seminary with Robertson; but the two emerged as very different ministers. Pat Robertson was drawn to the charismatic movement beginning to sweep the country and desperately sought out baptism by the Holy Spirit and the gift of speaking in tongues.

Robertson had done some preaching over the radio in Lexington and found he had a knack for it. His mother received word from a friend that a small television station was for sale in Portsmouth, Va., and asked, “Would Pat be interested in claiming it for the Lord?”

With $70 in his pocket, so the story goes, Robertson moved his family to Portsmouth and formed the Christian Broadcasting Network in 1960. Then he set about finding a church to ordain him.

Robertson chose Freemason Street Baptist Church in Norfolk to perform his ordination.

Returning to his Baptist roots, Robertson chose Freemason Street Baptist Church in Norfolk to perform his ordination. With a building designed in 1850 by the same architect who designed the U.S. Capitol, Freemason was a church for “high church” Baptists (Freemason left the SBC to align with the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship in 1993).

William Latane Lumpkin, then senior pastor at Freemason, had served Manly Memorial Church in Lexington, where Robertson was baptized, attended Sunday school and participated in Royal Ambassadors as a child. Robertson then served as minister of education at Freemason for 15 months and remained on the church roll, even though he rarely attended after his ordination, saying it was “boring.”

He later gave up his ordination when he ran for president in order to appeal to voters.

The tiny UHF Portsmouth station, which Robertson renamed WYAH as a nod to “Yaweh,” the sacred Hebrew name for God, had such a weak signal it only reached sections of Norfolk, Portsmouth, Virginia Beach and Hampton. But with a broadcast license for that small station, Robertson had his foot in the television door. It was from here that he would lay the groundwork for a worldwide media empire.

Pat Robertson

A technology breakthrough

The station struggled in its early days. In 1963, short on funds, CBN held its first telethon and recruited 700 subscribers to pay $10 a month to keep the station on air. CBN met its goal and in 1966 Robertson renamed his television program The 700 Club in honor of this achievement. Then, in 1977, CBN joined the three major networks and HBO and began transmitting its programs via satellite on RCA’s Satcom1. People in places like the Philippines, Japan, Canada, Taiwan, Puerto Rico and Hong Kong could now watch The 700 Club.

CBN was in the vanguard of a broadcasting shift that would change the way media was delivered and consumed. These advancements, and the way Robertson wielded them, would have far-reaching religious and political ramifications.

When Portsmouth challenged his tax-exempt status in 1979, Robertson moved CBN’s base of operations to Virginia Beach. Once a sleepy Southern resort town, Virginia Beach was on its way to becoming the most populous city in the state. Billy Graham delivered the keynote address for the new CBN’s grand opening, and it wasn’t long before tourists began coming to watch tapings of The 700 Club.

A university

Next door to CBN’s headquarters, Robertson bought 70 acres on which to build a graduate level university for “God’s glory.” He claimed he heard this commandment from God over lunch one day, but he must have drawn some inspiration from Jerry Falwell’s Liberty University and Oral Roberts University. ORU’s A.W. Coburn School of Law (including books, willing students and approved faculty) would later move from Oklahoma to Virginia to become the Regent University’s Law School.

The original school anchoring CBN University, later renamed Regent University, was the School of Communication and the Arts. With access to CBN’s production facilities and worldwide distribution network, such a school was a natural fit. Early communication faculty members, a mix of academics with varying Christian perspectives, were sometimes at odds with Robertson, who saw his university as a way to influence the courts and the culture. However, Robertson’s interest in CBNU waned as he became increasingly preoccupied with his political ambitions.

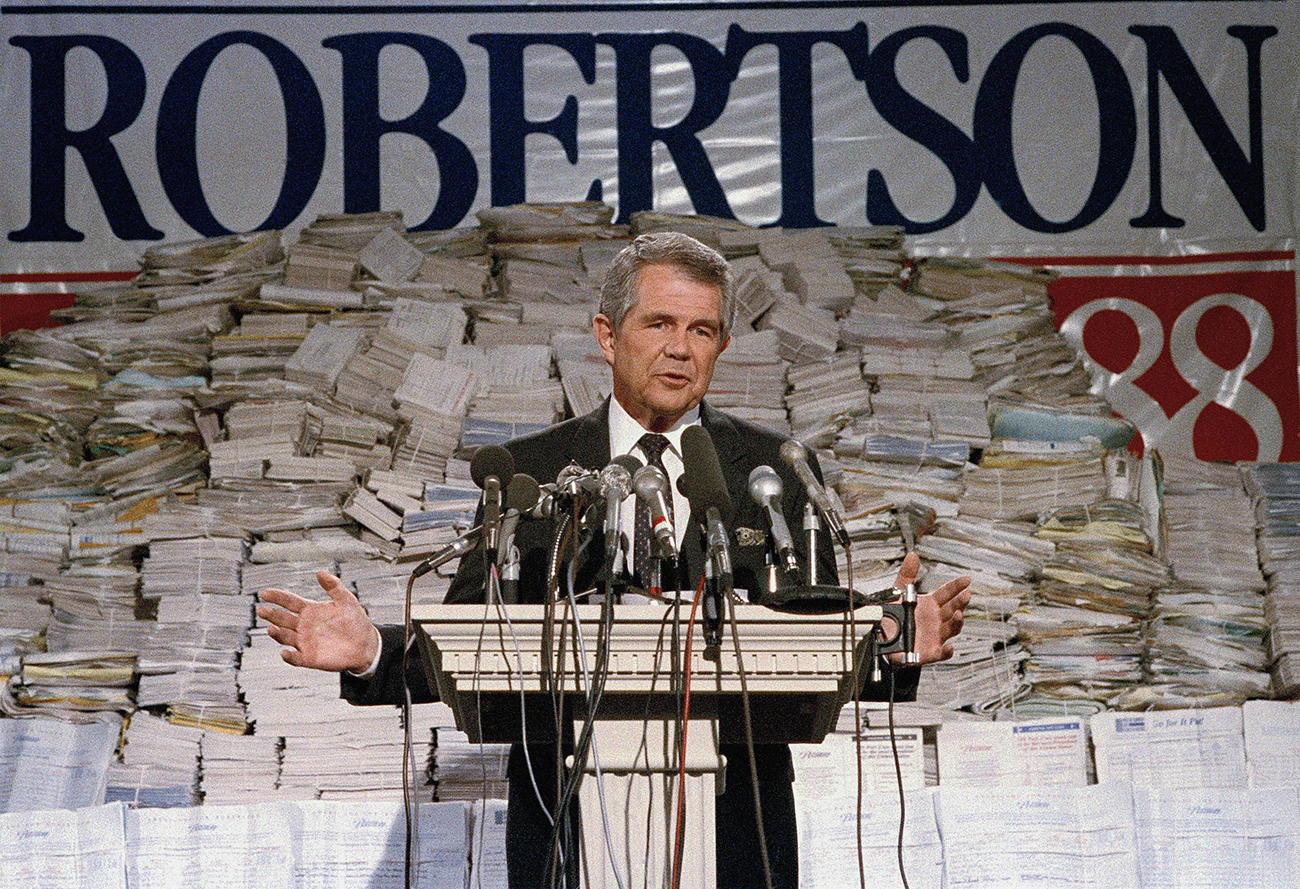

Pat Robertson stands in front of stacks of signatures for his presidential run as he announced his intentions to collect a total of 7 million signatures during a news conference in Chesapeake, Va., on Sept. 15, 1987. (AP Photo/Steve Helber, File)

Politics and presidential aspirations

Things weren’t working out for Robertson on the political front. In 1981, he had created a subsidiary called the Freedom Council to involve evangelicals more directly in the political process. Backed by money from donations to CBN, the group lobbied hard for a constitutional amendment establishing prayer in schools. With only tepid support from President Ronald Reagan, the measure flopped. Although beloved by evangelical Christians, Ronald Reagan himself was interested in their support more than their agenda.

Robertson decided if he wanted anything done, he would have to do it himself. In 1987, he announced, “I have made this decision (to run) in response to the clear and distinct prompting of the Lord’s Spirit. I know this is his will for my life.”

Once again, God agreed with something Robertson already had decided.

Pat Robertson, speaking at poster adorned podium, amid flurry of snowflakes, in front of his campaign bus. (Photo by Cynthia Johnson/Getty Images)

After some early success, his 1988 presidential campaign fizzled. Robertson deployed to swing states a reinvigorated Freedom Council backed by millions of dollars of contributions to CBN and armed with donor rolls from The 700 Club. His charity, Operation Blessing, established to deliver medical aid overseas, showed up in Iowa handing out money to farmers. Churches mobilized their buses to bring supporters, from inside and outside the state, to the Iowa caucus to vote for Robertson, giving him a second-place finish after Bob Dole. But it was momentum he could not maintain. He performed poorly on Super Tuesday and exited the race soon after.

With his political connections and media background, running for office should have been a breeze for Robertson. However, his charismatic beliefs and claim to have prayed Hurricane Gloria away from CBN (with an assist from the Outer Banks of North Carolina) did not play well on the national stage. The public also lumped Robertson with fellow televangelists, such as the Bakkers and Jimmy Swaggart, all of whom were embroiled in a series of scandals at the time, and Oral Roberts ,who was atop his prayer tower in Oklahoma telling his followers God would “call him home” if he didn’t raise $8 million.

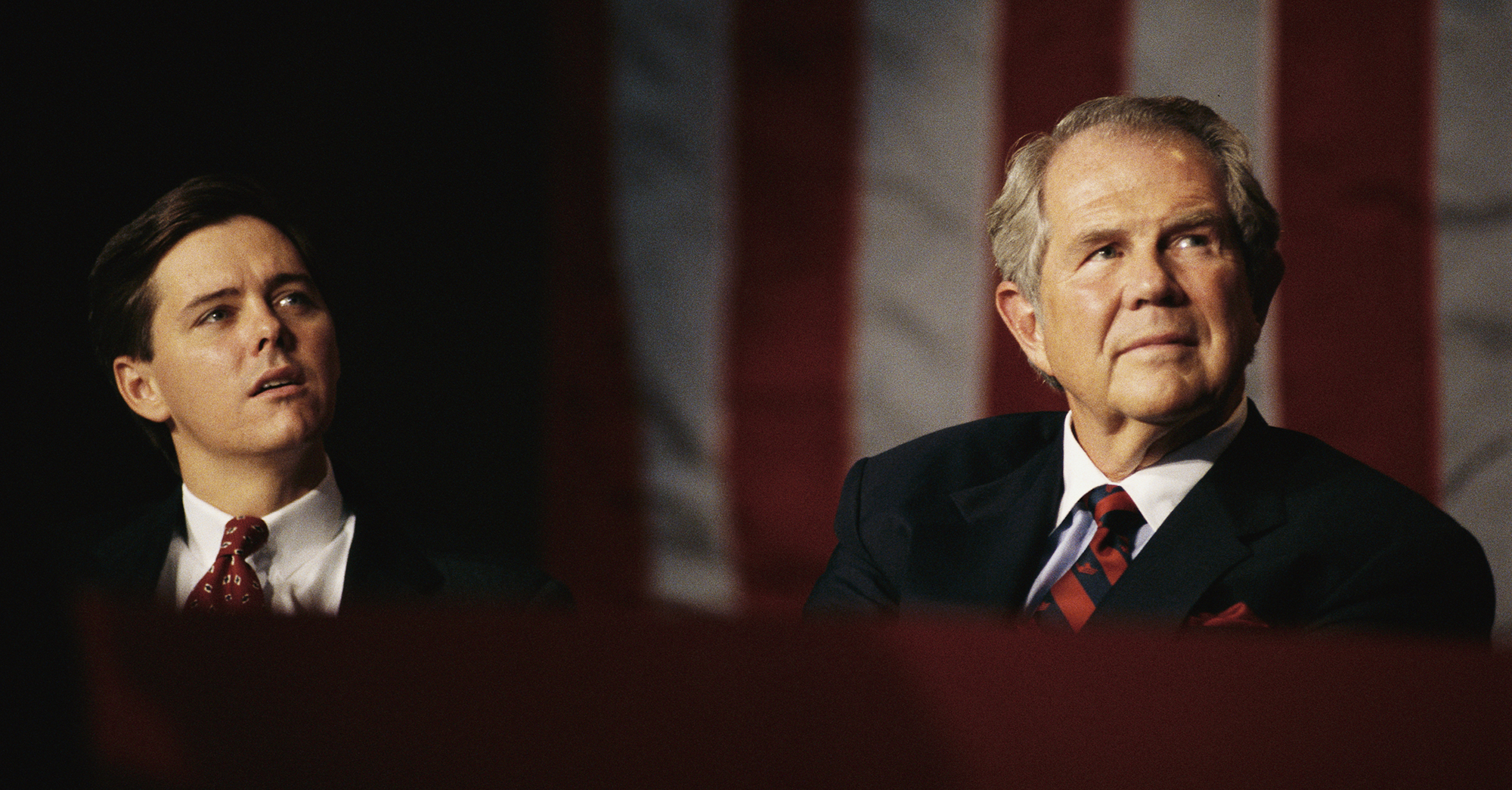

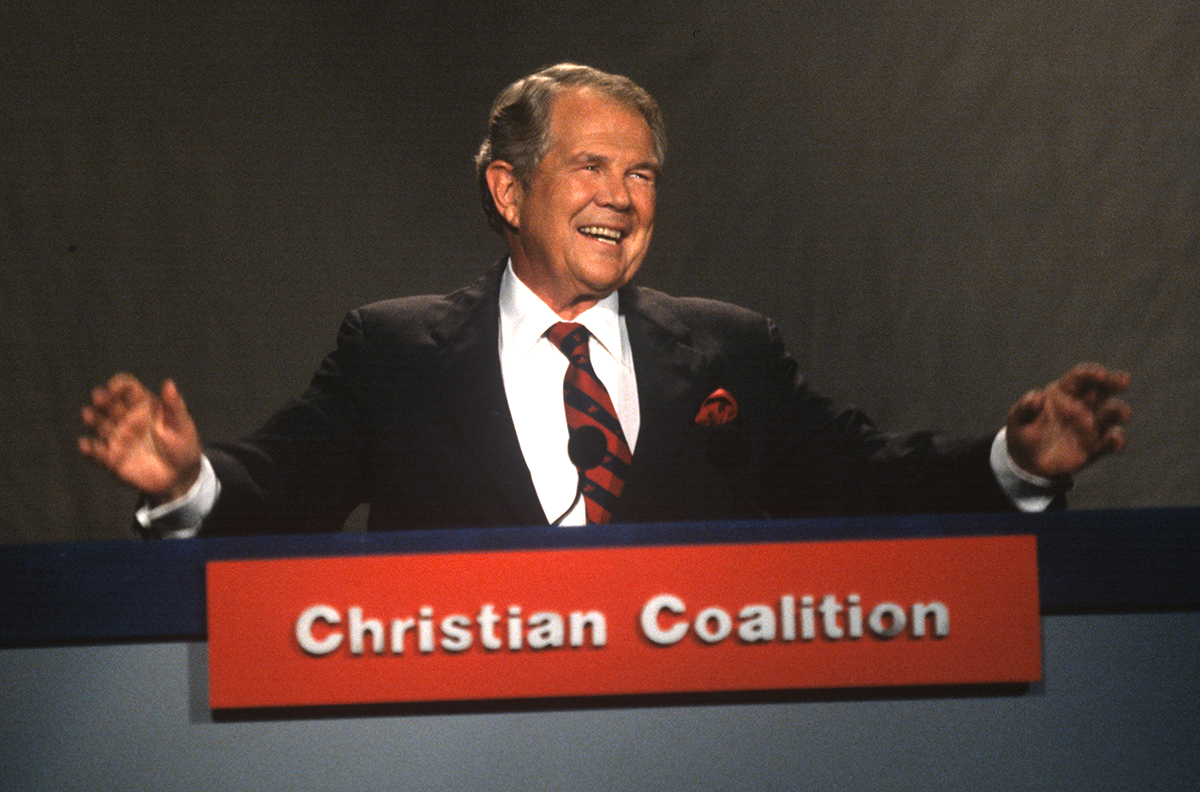

Ralph Reed and Pat Robertson at Christian Coalition Convention (Photo by © Wally McNamee/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images)

Political influence

Robertson lost his bid for the presidency but ultimately emerged a winner in the arena of political influence. He began to fancy himself a kingmaker in the Republican Party. Drawing on his mailing list of campaign supporters, many new to politics, Robertson founded the Christian Coalition in 1989 with the intention of remaking the Republican Party in his own fundamentalist image. He then hired wunderkind Ralph Reed to run it.

The Christian Coalition distributed millions of voter guides to local churches to “educate” voters about candidates’ stances on issues like gun control, abortion and school vouchers. Although skirting the lines of legality for a religious nonprofit, these guides were effective in helping Republicans win the House in 1994 and the White House in 2000.

Making millions

With his political influence on the rise, Robertson began exploring business ventures outside broadcasting. He created a multilevel marketing business selling overpriced vitamins and a protein powder called The American Whey. CBN pushed the products on its website as part of Robertson’s anti-aging regiment, asking, “Did you know Pat Robertson can leg press 2,000 pounds! How does he do it?”

Because viewers trusted his spiritual discernment, they also trusted in his money-making schemes. But as with all pyramid schemes, it was only Robertson and his family who were making money. Using contributions from CBN to seed these businesses, the Robertsons had little to lose and they gained much. All these ventures flopped for the viewers who bought into them.

Because viewers trusted his spiritual discernment, they also trusted in his money-making schemes. But as with all pyramid schemes, it was only Robertson and his family who were making money. Using contributions from CBN to seed these businesses, the Robertsons had little to lose and they gained much. All these ventures flopped for the viewers who bought into them.

Robertson’s biggest financial success came through CBN’s spinoff, The Family Channel. Originally funded by donations from viewers, Robertson realized it would soon prove too profitable for a nonprofit like CBN to justify owning. He and his son Tim separated The Family Channel from CBN by privately buying it from the network for $183,000. When The Family Channel’s stock went public, they made $90 million in profit.

Commenting at the time, James Dunn of the Baptist Joint Committee on Public Affairs said, “It may be as legal as it can be, but to me it’s immoral to build your business empire based on tax-deductible gifts to a ministry. (Pat Robertson) goes from ministry to marketing with very few pangs of conscience.”

The Robertsons later sold The Family Channel to Rupert Murdoch for $1.9 billion.

Working with dictators

Robertson’s conscience also was remarkably pang-free during his diamond mining days in the Democratic Republic of Congo, formerly known as Zaire. His contract with the country’s dictator, Mobutu SeSe Seko, stipulated 50% of the income generated would go toward humanitarian aid in the country; but the operation was a fiasco from the start. Robertson lost millions.

Mobutu, however, used his connection with Robertson to legitimize his tyranny. His soldiers gunned down 250 Christians gathering for a peaceful pro-democracy rally after church, many still clutching their Bibles and prayer books.

Immediately, Mobutu phoned his new friend Pat Robertson, who arrived three weeks later, embraced the dictator and called him a “fine Christian democrat.” Having learned nothing from this episode, Robertson entered into a gold mining partnership two years later with Liberian president and future convicted war criminal Charles Taylor.

Pat Robertson speaks at the Christian Coalition’s annual meeting on September 9, 1995, in Washington D.C. (Photo by Andrew Lichtenstein/Corbis via Getty Images)

Hysterical rants

Robertson’s high profile and broad exposure also gave him a national platform for his outrageous and often homophobic and racist rants. He told Disney World to look out for “earthquakes, tornadoes and possibly a meteor” after the park flew rainbow flags for its Gay Days. He agreed with Jerry Falwell and blamed 9/11 on “the pagans and the abortionists and the feminists and the gays and the lesbians.” He called for the illegal assassination of Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez and attributed the Haitian earthquake to a supposed “pact with the devil” the country made in 1804 to escape French control.

“Pat Robertson contributed greatly to some of the worst trends in American Christianity over the last 40 years,” said Mercer University ethicist David Gushee, speaking to Word & Way. “The fusion of conservative white Protestantism with the Republican Party, the use and abuse of supernaturalist Christianity to offer spurious and unhelpful interpretations of historical events, and the development of a conservative Christian media empire that made money and gained power in the process.”

Robertson claimed God would speak to him and then he would set out to bring that word to fruition; if he had an idea, then God must have planted it there. However, because Robertson believed God spoke directly to him, he never sought counsel from anyone else. As a result, there was an impulsivity and immaturity in his spiritual discernment that followed him throughout his ministry and business dealings.

Robertson claimed God would speak to him and then he would set out to bring that word to fruition; if he had an idea, then God must have planted it there. However, because Robertson believed God spoke directly to him, he never sought counsel from anyone else. As a result, there was an impulsivity and immaturity in his spiritual discernment that followed him throughout his ministry and business dealings.

Because he was so convinced his own plans and prejudices were God’s, he also believed the ends justified the means. His example taught many other Christians and politicians to think the same way, even about him. Robertson was willing to take the Social Security checks of seniors and step over the graves of murdered Africans to fund his schemes.

In much the same way, Republicans entertained his illuminati conspiracy theories and satanic panic in exchange for votes from the Christian Coalition. It’s a trade-off they continue to make with Donald Trump and the MAGA wing of their party.

The charismatic movement already was in motion when Pat Robertson joined it, but he managed to mix it with the reactionary conservatism of Nixon and Reagan and had the means to distribute the resulting caustic cocktail through his television network.

A ‘new Gnosticism’

Many of us with a different perspective on faith and politics weren’t tuning in, but we made a mistake in writing off those who were.

Pat Robertson preached a “new Gnosticism” full of end times conspiracy theories only he could unravel and only those “in the know” could understand. His daily appearance on the small screen in people’s homes created an intimate connection through which to share his secret knowledge of the Bible, empathize with viewers’ cultural grievances and agitate their fears. Robertson sowed the seeds, and QAnon, Tucker Carlson and Donald Trump have reaped the harvest.

Regent University chancellor Pat Robertson delivers remarks at a campaign event for Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump at Regent University October 22, 2016, in Virginia Beach, Virginia. (Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images)

No doubt Pat Robertson fancied himself a modern-day prophet sprung from the pages of the Hebrew Bible, calling down fire and brimstone on sinners, forecasting doom, waiting like Jonah to watch the world burn. But unlike Jonah, he never seemed to comprehend God’s inherent mercy.

Other prophets such as Amos (2:6-16), Zephaniah (3:1-2), and Isaiah (5:8) were much more concerned about the abuse of the poor and marginalized than they were any individual’s perceived sins — and admonished those who lived in luxury while the people suffered. They called folks to return to a God who established sabbath and jubilee to ensure abundant life for everyone.

It’s revealing that in his profession of faith, Robertson says he understood God’s love poured out for him but completely overlooked the fact that God’s love and grace extends to others.

Despite the broadcast networks, the political power, the billions in the bank, much of what Pat Robertson had to show for his life in the end is little more than a noisy gong and a clanging cymbal because there was little if any visible love behind it. I say much because during my time at Regent and CBN, I did meet loving, caring people who were doing real ministry within the confines of the media empire Robertson created.

Many of these people were women and minorities who had come from all over the world to learn and work and make a difference in an industry that was, and in many ways still is, primarily the realm of white men like Pat Robertson.

But Robertson was so obsessed with what he wanted to do and who he wanted to hate in God’s name, that he missed what God was doing behind the scenes and the reality of God’s love. With his death, the loss is not the man himself, whose arrogance and vitriol will not be missed, but the loss of what could have been.

Kristen Thomason is a freelance writer with a background in media studies and production. She has worked with national and international religious organizations and for public television. Currently based in Scotland, she has organized worship arts at churches in Metro D.C. and Toronto. In addition to writing for Baptist News Global, Kristen blogs on matters of faith and social justice at viaexmachina.com.