The Acts of Peter is a fragmented, early Christian text made up of three parts: the “Coptic Act of Peter,” the “Acts of Peter the Apostle,” and the “Martyrdom of the Holy Apostle Peter.” These writings are not included in the Christian biblical canon and are considered apocryphal.

The Coptic Act of Peter, the first of the three parts, is a short two-chapter-long narrative of Peter’s 10-year-old unnamed and disabled daughter.

Mallory Challis

In the narrative, Peter’s daughter becomes paralyzed after a man spying on her while she is bathing becomes sexually aroused. The disabling of her body is intended to prevent other potential suitors from lusting after her, likely because of the social shame attached to disability in ancient society, as well as ancient ideals correlating disability with infertility. Men of this time likely would not seek Peter’s daughter out as a marriage partner if her body remained unhealed.

Peter tells this story after being prompted by a crowd member who questioned why he would not heal his own daughter. He laughs at this remark, heals her in front of the crowd to prove that he has the power to, then immediately un-heals her, leaving her paralyzed as she was before.

Throughout this narrative, Peter’s daughter has no dialogue, nor does she have agency in what is done to her body. This story is told again by a later Christian writer in the Acts of Nereus and Achilleus in a narrative that attempts to offer her more agency by giving her the name “Petronilla” and recording that she prayed over healings and helped others obtain salvation. She also is regarded as a saint and in the early centuries was considered a martyr.

In this article, I will use the name Petronilla with the understanding that although these differences are present in the two narratives, they represent the same person and/or idea.

“Peter’s healing and unhealing of Petronilla seems like our modern concept of sexual purity.”

Peter’s healing and unhealing of Petronilla seems like our modern concept of sexual purity, hinting at the transactional blame placed upon the bodies of women when men experience sexual temptation. In fact, rather than punishing a man for making sexual advances on his 10-year-old daughter, Peter in this story subjects Petronilla to physical ailment so that her body no longer will bring others to sin, even though she has done nothing wrong.

This narrative portrays Peter utilizing his healing and unhealing abilities to assert power and control. But that is not necessarily a good thing, even though Peter is an apostle.

We can critique this apocryphal narrative by recognizing how he disregards the well-being of Petronilla by forcibly disabling her, refusing to heal her, then using her condition to display his power in front of crowds. There is a lot to unpack in this narrative.

Passages like this, in which disability is viewed as a form of punishment or flaw that imposes a spiritual hindrance upon a person can be problematic for readers. Of course, ancient conceptions of disability were not as good as ours today. Modern science allows us to understand much more than early Christian writers ever could.

“There are plenty of canonical passages wherein persons with disabilities are viewed as lowly, then healed and rejoiced over.”

But modern readers cannot ignore the text’s repeated subjugation of persons with disabilities. There are plenty of canonical passages wherein persons with disabilities are viewed as lowly, then healed and rejoiced over.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, one in four adults in the United States has some type of disability, with the highest percentage of people living with disabilities being in the South. That is 61 million American adults total.

Further, one in three disabled adults does not have a regular health care provider and has been unable to meet their health care needs because of the cost in the past year. One in four of these adults did not have a routine check-up in the past year.

Disability rights should be extremely relevant to our readings of texts like this.

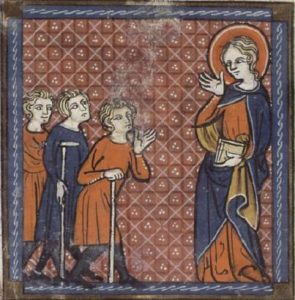

Saint Petronilla and the Sick, from 14th-century French manuscript.

Passages like these have an impact on the disabled community, especially when interpreted by able-bodied and neurotypical readers, like myself, in ways that do not aim to illuminate the importance of disabilities. How can we find power among disabled characters within these troubling texts?

Our first step is to recognize the power dynamic at hand in these passages. Peter, both as the patriarch of the family and as an apostle, has a great deal of power over Petronilla. She depends on him to care for her and can only be healed if he chooses to do so. Yet, because her disabled body is useful in his ability to deliver his message, she is not healed.

Our second step is to consider the problematic nature of our desire to heal everyone with a disability. Often, able-bodied people view disability as an obstruction of agency. I and other able-bodied writers must take care when making assumptions about texts and narratives such as these.

“I and other able-bodied writers must take care when making assumptions about texts and narratives such as these.”

In some ways, disability may obstruct agency, but this can often be because we lack in our efforts of making the world an accessible place for everyone. Petronilla’s narrative is messy because we do not have access to her opinion about being disabled. Maybe she is bitter toward her father for utilizing her body in such a public and socially marginalizing way. Or perhaps she does not want to be healed because she, too, wants to reject sexuality in protest of the spying man’s perverseness. We as readers can speculate, but we cannot make that decision for her.

What we do know is that Peter’s use of her body strips her of this choice completely as he decides two things: the perpetual disabling of her body, and the shame that her disabled body symbolizes. But modern readers can reject these things, recognizing that although she is forcibly disabled, and ancient readers would have viewed her as a social outcast, it is her disabled body that drives the narrative.

Here is my attempt to redeem her narrative.

By simply existing, Petronilla forces Peter, the crowd and all the men who see her body to move around the space she takes up. Her disabled body is responsible for the salvation and spiritual edification of others (although against her own will) and is the example by which Peter bolsters and solidifies his message. Without her body, Peter would have no power.

Modern readers could view this narrative as a triumph for Peter’s ministry, asserting sexual chastity against all odds.

Or we could empathize with the real main character — Petronilla — and see how her body’s willfulness in this narrative rejects sexualization and patriarchal power by forcing those around her to consider how important her disabled body is. She becomes a holy spectacle around which the narrative survives.

Her disability, although intended to be a punishment, is the most powerful aspect of her story.

Mallory Challis is a senior at Wingate University and serves this semester as BNG’s Clemons Fellow.

Related articles:

As Americans with Disabilities Act turns 30, barriers remain

How the male-centered image of God marginalizes women and disabled persons | Opinion by Mallory Challis

Pastor counsels churches to greet disabled with compassion, not exclusion or fear

I knew the truth about women in the Bible, and I stayed silent | Opinion by Beth Allison Barr