Data now shows the extent to which Americans are avoiding the “P” word – as in politics.

Nearly half of American adults say they have stopped talking politics, the Pew Research Center announced earlier this week.

Michael Usey

Preachers have seen it for quite some time.

“In general, Americans are uncomfortable with conflict,” said Michael Usey, the senior pastor at College Park Baptist Church in Greensboro, North Carolina.

As the conservative-versus-liberal construct has grown increasingly hostile, it’s also become increasingly personal, he said. It’s a dynamic Usey and other ministers say they have watched from the pulpit, from their desks and in their own encounters with friends and relatives.

“People come in my office about the things keeping them up at night, the interactions with extended family, the parenting issues that are coming up as a result of the political arena,” Usey said.

‘We need to stay away from it’

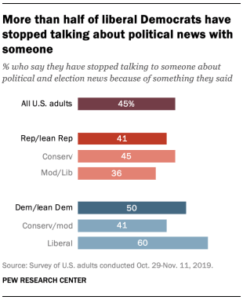

According to Pew, 45 percent of U.S. adults said they have ceased discussing politics and election news due to online or in-person encounters.

Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents are the most likely to avoid such interactions, at 50 percent. That’s compared to 41 percent of Republicans and Republican-leaning independents, the research organization found.

“How closely one follows news about politics and the election also comes into play,” Pew reported. “The closer people follow political and election news, the more likely they are to say they have stopped talking to someone about it.”

Solutions – if there really are any – vary. At least within their congregations, ministers say they caution against partisan talk.

At Franklin Baptist Church in Franklin, Virginia, there is a conscious effort among lay leaders and clergy to skirt political issues, said its senior pastor, Charles Qualls.

Despite being “staunchly split” along partisan lines, he said, the congregation has long been intentional in preventing those divisions from creating fissures within the membership.

Charles Qualls

“They have always fought off needless external threats to its culture,” Qualls said. “That’s how they’ve made it from 1871 to now.”

When called by the church, Qualls said he was specifically charged with helping maintain internal harmony.

“So, I challenge people pretty regularly to be more careful and mindful of the words they use,” he said.

Sunday school classes are asked not to discuss partisan politics as parts of lessons, Qualls added.

“It’s just fraught with too many bad possibilities,” he said.

That applies to social media use, too.

“You see people who are loving and serving in ministry and they are mission-minded, and then you watch what they post on Facebook and you cringe.”

‘Some humility around that’

From a ministry and even personal standpoint, the guiding motivation should be to preserve the connections between people, said Doyle Sager, the lead pastor of First Baptist Church in Jefferson City, Missouri.

“Relationships are more important than trying to win arguments,” he said.

“In church, we need to stay away from it,” Sager said of political topics. “It’s just not a good thing to engage.”

Such conversations are rarely logical and usually devolve into emotional spats.

Doyle Sager

“Politics has always been emotional, but it seems the emotions are all ramped-up now,” he said.

People of faith have contributed to the situation, Sager said.

“The church has not taught or modeled a good theology of conflict.”

If conversations around politics are to be healthy, he added, participants should avoid ascribing negative motives or questioning the faith or patriotism of others.

“I plan a sermon in the early Fall that says if there is any organization that ought to model civil dialogue and respect, it should be the church,” Sager said.

That modeling likely must avoid talking past others, Usey said.

“If there is a way out of the morass, it’s going to involve some really deep listening on our part,” he said. “What does it mean to really listen and to act on the concerns of other people?”

It means setting aside agendas and fear, he said. It requires swapping the “bazooka approach” of political debate for discourse that accommodates the views of others.

And that in turn requires humility, he said.

As an example, Usey recalled a man who approached him about joining College Park Baptist.

The man described himself as a conservative who practiced concealed carry and voted for Donald Trump. But he had been booted from another church because he affirms LGBTQ people.

“He said, ‘is there room in your church for me?’” Usey recalled.

“I said yes, because we are all trying to get it right and hopefully there some humility around that.”

Related commentary:

Doyle Sager: In a messy election year, let’s remember that the ‘Golden Rule’ applies to politics too