The formal death notice of Herman Paul Pressler III, a former Texas state appellate judge and the chief strategist behind a now 45-year rightward shift in the 14 million-member Southern Baptist Convention, hit me like a brick.

For months, I had been apprised of his declining health. For years before that, he had been largely out of sight and suffering the effects of a progressively debilitating condition. On Saturday, June 15, a few dozen members of Pressler’s family and remaining friends gathered at a small funeral chapel in Houston to grieve their loss and celebrate his life.

I had thought on occasion over the past several years about his death and prepared for its eventuality. But when the news finally came, a flood of unanticipated sadness overwhelmed me. As the obituaries were published across the major newspapers and online, I had to stop reading them. Not because they were untrue or unfair, but because there are only so many times a man should read the regurgitations of a friend’s reported transgressions.

“When the news finally came, a flood of unanticipated sadness overwhelmed me.”

And yes, Paul Pressler was my friend. And I already have missed him for many years.

Meeting The Judge

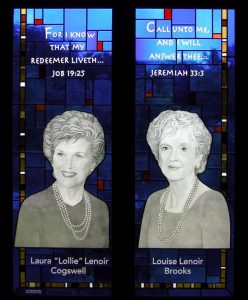

I first met “The Judge,” as he was most affectionately called by those who knew firsthand his tremendous generosity and unconditional kindness, in November 1994 at the annual meeting of the Baptist General Convention of Texas. As a Baylor sophomore (I graduated a year early from high school and entered Baylor with a full year’s worth of credits under my belt), I was introduced to Judge Pressler by Laura Cogswell and her sister, Lou Brooks, two card-carrying members of Phyllis Schlafly’s Eagle Forum and movement conservatives in Southern Baptist life.

Laura Cogswell and Lou Brooks enshrined in stained glass at Southwestern Seminary. (Photo by Don Young Glass Studio)

With Pressler’s help, I made a motion the next year at the BGCT meeting in San Antonio to investigate “heresy” at Baylor University, citing a popular New Testament textbook that was then being used in the religion department. That evening, Judge Pressler took a group of us — including Cogswell and Brooks — to Ruth’s Chris Steakhouse in San Antonio. As he often did, Judge Pressler picked up the tab for the group and invited me to visit him in Houston. His home, he told me, was always open for me to stay if ever I needed.

Months later, as I was preparing to attend the SBC annual meeting in New Orleans, I faxed the judge a handwritten letter telling him I would be in the Crescent City and hoped to see him there. He quickly faxed back several handwritten pages offering to pay my expenses in New Orleans in exchange for some assistance with his son, who suffered from a medical condition I never fully understood. I agreed, went out and bought a new suit and tie, and traveled to New Orleans for a week with the judge and his family.

It was there in New Orleans, following the president’s address by SBC President Jim Henry, that the judge asked me to accompany him to a private ballroom where a reception would be hosted for the newly elected president, Tom Elliff of Oklahoma. We were early to the room and sat there alone — just the two of us talking — until a portly and grayish-red-headed man entered the room. And so it was that on that evening of June 12, 1996, I was first introduced to the other half of the legendary coalition, Paige Patterson, then president of Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary in North Carolina.

“It was on that evening of June 12, 1996, I was first introduced to the other half of the legendary coalition.”

The three of us sat for a while before others arrived, and I listened to them express their frustrations with Henry’s address. Henry, in an effort to encourage Southern Baptists to move past the “wartime” effort of the Conservative Resurgence, had done the unthinkable and suggested leaders like Patterson and Pressler should follow the example of ancient Roman leader Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus by declaring victory and “returning to the farm.”

The mood that night was lighthearted. The two of them joked and teased each other. And I sat in quiet amazement, feeling as though some providential fortune had befallen me to hear these two men — whom I’d already learned to respect as heroes of the faith — talk about the convention’s past and future battles.

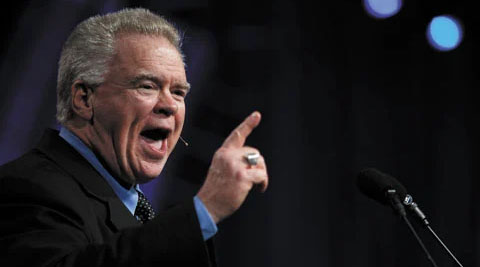

Paige Patterson addresses the Southern Baptist Convention annual meeting in San Antonio., Texas, in 2007. (Photo by Matt Miller, Baptist Press)

Southeastern College

Later that evening, Pressler suggested to me that I should leave Texas and move to North Carolina to attend the new college Patterson had launched on the Wake Forest campus. Within months, I followed Pressler’s advice and with his generous help and the financial support from longtime members of Bellevue Baptist Church, I enrolled at Southeastern Baptist Theological College.

The next year in Dallas, Pressler would again underwrite my convention attendance after a pre-meeting visit to Houston with another Southeastern student. A few days before the annual meeting, the judge, Nancy, their son and the two of us piled into the Presslers’ blue Cadillac and made the four-hour trek north, stopping at a rest area along the way to have a picnic lunch Nancy had prepared for us.

In 1998 in Salt Lake City, in Atlanta in 1999 and again at the 2000 SBC annual meeting in Orlando, Judge Pressler paid for my hotel and meal expenses in exchange for my assistance with his son during the annual meeting. At other times, the judge invited me to attend meetings of the Council for National Policy with him. He also took me to meetings of the International Mission Board, and he generously funded the first two international mission trips I ever took.

While at his home one Saturday evening in 1999, Judge Pressler became ill and determined it was unwise for him to teach his Sunday school class at First Baptist the next morning. Cal Thomas, the conservative columnist, also was staying at his home that evening but was unable to fill in. So it fell to me to teach Pressler’s adult Sunday school class.

A few days later, the judge invited me to join him at the Houston Country Club for lunch, where I met a Texas Railroad commissioner and a former Republican congressional leader. He also invited me to the University Club, attached to the Houston Galleria, and I rode stationary bikes and sat in the steam room and sauna with him. At no time — not once ever — did he act inappropriately or even suggest anything immoral. I had no reason to suspect any character issue or moral deviance on the judge’s part. He was always a kind, courteous, generous and encouraging friend.

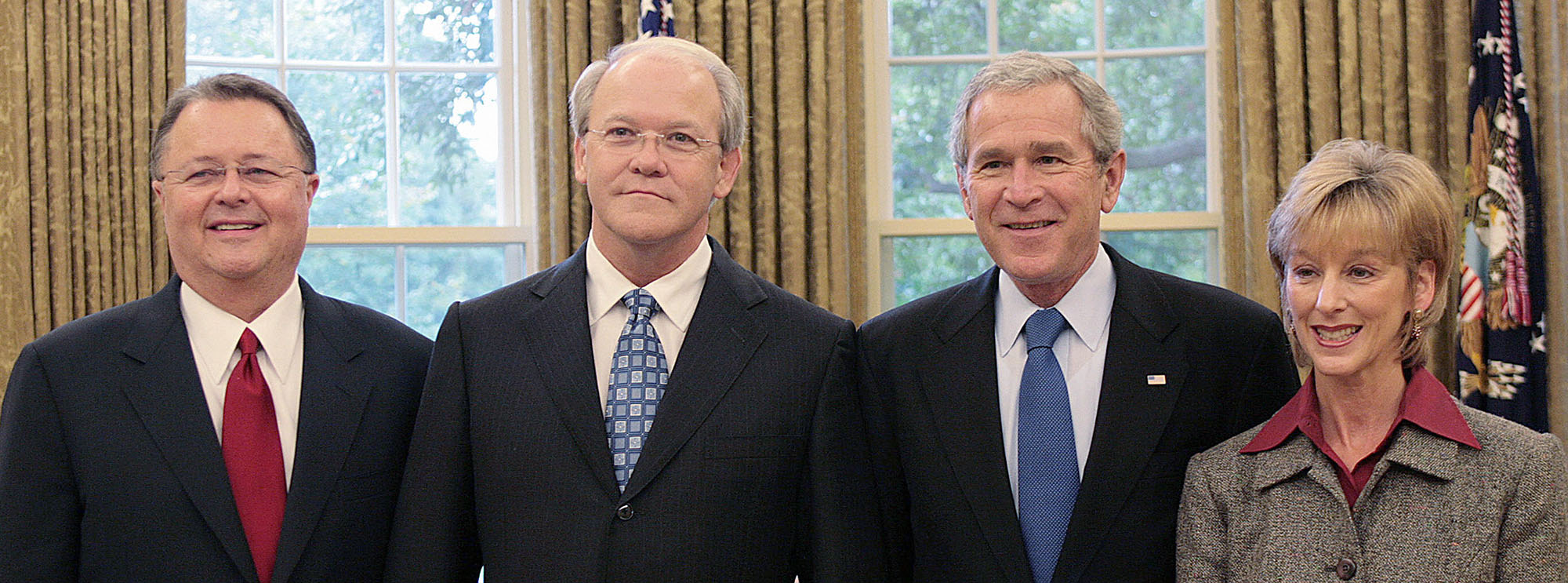

President George W. Bush poses with Southern Baptist Convention President Frank S. Page (2nd L), Dayle Page (R), and SBC Executive Committee President Morris Chapman October 11, 2006. (JIM WATSON/AFP via Getty Images)

Inklings of allegations

It wasn’t until the spring of 2006 — during the fiercest of those early days of Baptist blogging — that I heard the first report of Pressler’s alleged offenses. A religion reporter for the Dallas Morning News called me and told me one of his colleagues, an investigative reporter who was working on a story involving a Texas-sized tale of a 22-year-old street hustler, Baptist preachers, murder, and the prison sentence of a young Black man, wanted to talk. Later that week, I went to lunch with the reporter, who asked me what I knew about Judge Pressler.

I sat there incredulous. A few years earlier, according to the court documents I was shown, Pressler had settled a civil lawsuit with a young man who accused him of “assault.” The court records did not indicate the assault was sexual in nature, but the circumstances of the alleged assault raised all kinds of red flags.

“Have you ever experienced anything like this,” he asked me.

“Not ever,” I told him.

“Do you know of anybody who has?” he pressed.

“Not at all,” I replied.

I left that lunch meeting rattled and placed a call to a denominational executive who was intimately familiar with the case that prompted my initial contact with the Dallas reporter. I asked him if he had heard anything about the settlement arising from an alleged “assault” in a Dallas hotel room. He had heard the same thing I had, but neither one of us were interested in asking the judge about it.

It was a settled matter, and the settlement agreement was sealed. I never thought about it again.

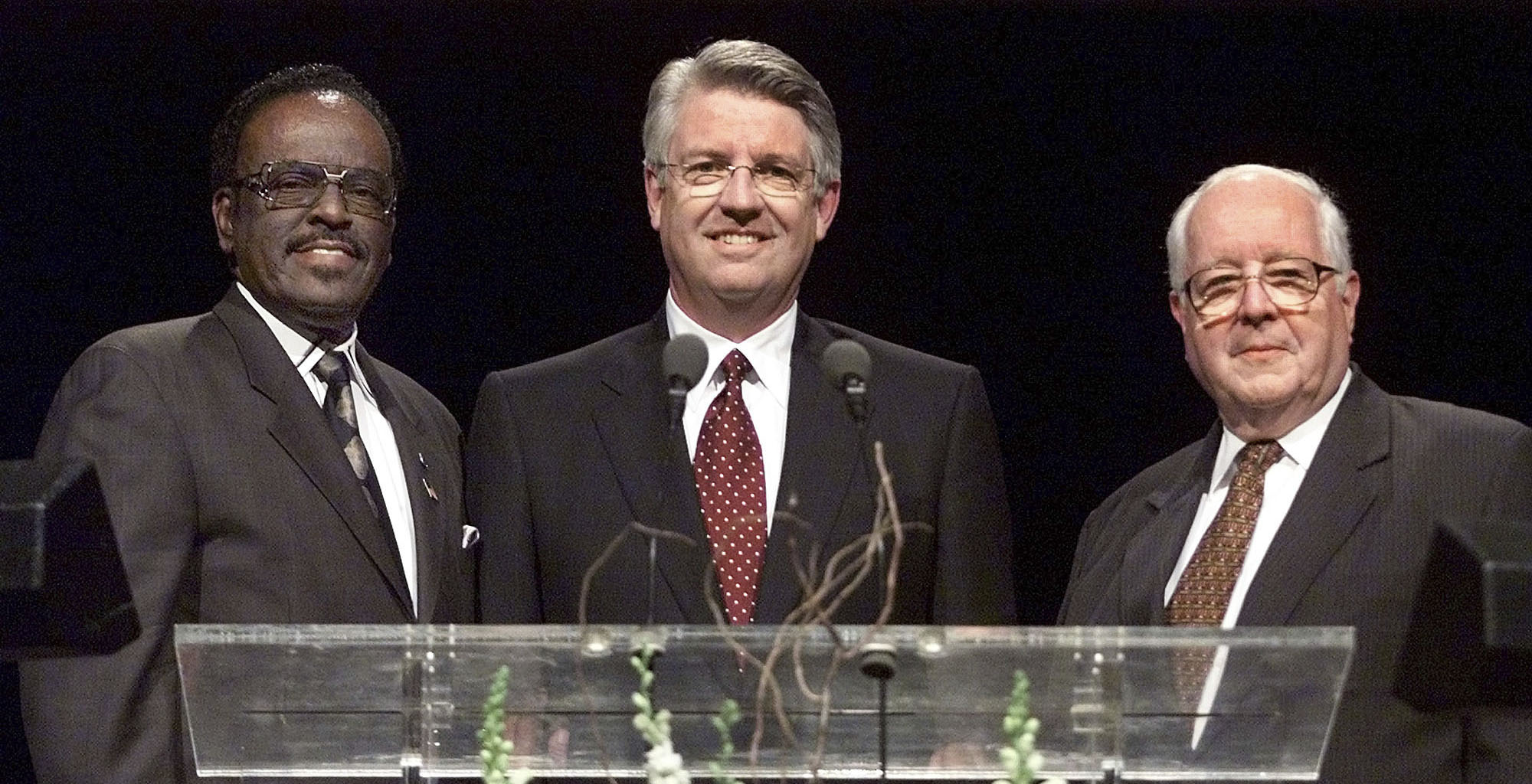

In 2002, newly elected officers of the Southern Baptist Convention pose for a photo: Second Vice President E.W. McCall of Lapuente, Calif., President Jack Graham of Plano, Texas, and First Vice Pesident Paul Pressler of Houston. (AP Photo/Tom Gannam)

Life moves on

Over the next few years, the judge and I corresponded and talked on the phone numerous times. I saw him at a few more conventions. We met for dinner during one visit he made to the Washington, D.C., area for a political event. And then life directed our paths in different directions.

The judge largely retired from active involvement in the SBC, and I channeled my energies to legislative work in the nation’s capital.

“The judge shared with me that he and Patterson had experienced a fracture in their friendship, largely over our continued friendship.”

At one point, the judge shared with me that he and Patterson had experienced a fracture in their friendship, largely over our continued friendship. Patterson wrote Pressler a letter — a copy of which I obtained — telling him he wanted no contact with him so long as the judge maintained a friendly relationship with me. The judge turned over copies of letters back and forth with Patterson that were exchanged in the run-up to the 2006 annual meeting that further indicated their broken relationship.

Those letters show how Patterson — along with R. Albert Mohler Jr. — was backing the candidacy of Arkansas megachurch pastor Ronnie Floyd in his quest for the convention presidency. Pressler, who never had gotten over Floyd’s whisker-thin defeat a decade earlier of Virginia layman T.C. Pinckney to serve as chairman of the powerful SBC Executive Committee, refused to back Floyd and supported the candidacy of Tennessee pastor Jerry Sutton instead.

Both men lost to a relatively unknown South Carolina pastor named Frank Page. To some degree, I was instrumental in helping to secure Page’s election along with the strategic collaboration of other bloggers who were taking the convention by storm at the time. Pressler wasn’t enthusiastic about Page’s election, but he was gracious as ever and didn’t allow it to come between friends.

Patterson, on the other hand, seemed to have grown deeply bitter over Pressler’s refusal to back Floyd (thus resulting in the election of Frank Page and the elevation of Cooperative Program support over party loyalty as a prerequisite to convention office) and his unwillingness to end a friendship with me in the fallout of the 2006-07 controversies.

By the time charges of rape were made public against Pressler in 2017, Patterson and he had partially mended fences although Patterson, by then president of Southwestern Seminary, was too preoccupied to help Pressler on account of growing charges of his own institutional mismanagement and mishandling of abuse.

“The two men … had no more capital to spend in defense of each other.”

The two men, who had decades earlier forged a coffee shop confederacy to expose the theological aberrations they perceived in Southern Baptist agencies, had no more capital to spend in defense of each other. To my knowledge, their interactions have been limited ever since.

Final judgment

And last week, while Paul Pressler’s body lay dead in a Houston funeral parlor, Patterson was still slowly walking the halls of the convention that once celebrated and revered him before the truth all started to come out in court filings and convention reports.

Before he died, Pressler appears to have settled all his earthly business and made acceptable financial restitution to those who accused him of wrongdoing. Patterson, on the other hand, it seems, has some outstanding scores to settle. And while Pressler died in Houston surrounded by family who love him and friends who have forgiven him, Patterson remains defiant as he awaits rulings from the Texas Supreme Court and the Fifth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals.

Paul Pressler (left) and Paige Patterson, architects of the SBC takeover, sit at Cafe duMonde in New Orleans June 9, 1990, comemmorating their meeting at the same spot 20 years earlier to conceive the plan to gain control of the nation’s largest non-Catholic denomination. (Photo by Thom Scott)

To put a point on it, Paul Pressler has now appeared before the only courtroom where any man is ever guaranteed a completely fair trial. Patterson still has pending legal action against him in both federal and state courts. Had Pressler’s cases ever gone to trial, I would have willingly testified that my personal association and frequent interactions with him were substantially different from the characterizations made by other young men who worked alongside and traveled with the judge through the years.

I owe it to my friend to publicly state that in 30 years of our friendship, I never witnessed or experienced anything like what others have accused Judge Pressler of having done. On the other hand, for almost those same 30 years, I’ve seen multiplied and convincing evidences of what his onetime convention collaborator has been alleged to have done, repeatedly and without a hint of remorse.

I truly grieve Pressler’s death this week, although I can respect the sense of closure and even moral satisfaction that his accusers must feel. And in a weird way, I similarly grieve the shell of a man I saw struggling to perambulate while grousing in Indianapolis. In the providence of God, the effects of aging and his ultimate death kept Pressler from attending recent annual meetings where he would have been forced to walk the halls and endure potential scowls and sneers.

Patterson, on the other hand, chooses to attend the annual meetings and cast his ballots for those candidates and causes that reflect his own warped views on abuse reform and his increasingly eccentric theological commitments. He also got to see a censure motion against one of his former seminary colleagues brought to the floor, an experience Patterson himself never has endured. In a way, it was both tragic and poetic.

And the fact remains that it never had to be this way. In the end, it is my prayer that Pressler’s lost reputation and death alongside Patterson’s continued legal jeopardy and diminished stature will serve as a permanent warning to all Southern Baptists — be they powerful seminary presidents or activist laymen — of what can happen when zealous ecclesiastic reform gets entangled with personal ambition, political machinations and the corrupting power that still haunts the nation’s “largest Protestant denomination.”

Benjamin Cole

Benjamin S. Cole is a crisis communications consultant who lives in Plano, Texas, and tweets about SBC life under the pen name The Baptist Blogger.

Related articles:

Paul Pressler died and the SBC said nothing

Confidential settlement reached in Pressler sexual abuse case

Patterson and Southwestern settle with Pressler’s accuser

New court documents show First Baptist Houston leaders knew of allegations against Pressler in 2004