Princeton Theological Seminary announced Jan. 25 that it has changed the name on its campus chapel to avoid further association with a slaveholding professor.

Samuel Miller was the second professor hired at the Presbyterian seminary. Born in 1769, he was a native of Delaware and joined the seminary faculty in 1813 after holding a pastorate in New York City.

Samuel Miller

Princeton’s audit of slavery in its past, published in 2019, identified Miller as someone who “employed slave labor in his lifetime, including while he lived in Princeton.”

That report quotes Miller’s son explaining his father’s position: “But greatly as he disliked the institution (of slavery), he did not, we have seen, consider slaveholding in itself, of necessity, a sin; and even during the earlier part of his residence in New Jersey, at different times, held several slaves under the laws providing in that state for the gradual abolition of human bondage. In fact, he held them only for a term of years, in a sort of apprenticeship, excepting in one case, in which he found himself deceived by the vendor as to the age of a man-slave, and obliged, by law, to hold him and provide for him for life.”

The report summarizes: “While Miller did not like slavery and hoped for its eventual demise, he did not consider the use of slave labor as sinful and was not averse to employing it himself.”

In a Jan.25 letter, Princeton Seminary President Craig Barnes said the seminary’s board of trustees just that day had voted unanimously “to disassociate the name of Samuel Miller from the chapel.”

The building will now be known as Seminary Chapel, he said. “The board also voted to create a task force charged with developing guiding principles and decision-making rubrics for naming, renaming and conferring honor in buildings and spaces. This task force will include students, faculty and alumni.”

Trustees issued their own statement that said “all official conversations concerning the names of buildings, old or new, and other forms of honor on sites and objects will cease until the seminary officially adopts a set of governing principles based on the work of this task force.”

Craig Barnes

The trustee statement explained that removing Miller’s name from the chapel “is another step in Princeton Theological Seminary’s earnest commitment to greater equity, including reformation and repair of yesterday’s wrongs.”

After releasing its historical audit and announcing a series of reforms and new initiatives, the seminary’s response was deemed insufficient by the Association of Black Seminarians and others. Among the concerns was that the seminary was allocating only a small fraction of its assets — including a $1 billion endowment — toward reparations when the seminary was founded and built on the legacy of slavery.

Since 2019, the seminary has dedicated 35 full scholarships plus stipends to descendants of the enslaved and those from historically underrepresented groups to pursue masters’ and doctoral degrees; named the seminary library for Presbyterian minister and abolitionist Theodore Sedgwick Wright, the first African American graduate of the seminary; enhanced programming resources for the Betsey Stockton Center for Black Church Studies; and incorporated the historical audit into the first-year curriculum for every master’s-level student.

Both Barnes and the board thanked the Association of Black Seminarians for its persistence in advocacy.

“It has been a moving testimony of covenant community to see how diverse students united to lament the pain of having to worship in a chapel named for a slaveholder, opponent of abolitionism, and advocate for the American Colonization Society, which sought to send freed Blacks to Africa,” Barnes said.

Chapel interior

Yet the fact remains that Miller was, indeed, one of the seminary’s founders.

“Samuel Miller is, and will always be, a part of Princeton Theological Seminary’s story,” Barnes said. “We are not trying to remove him from our history. Yet the board chose to disassociate his name from a place of tribute in the chapel, where the community gathers into the one body of Jesus Christ. As part of the historical audit, we want to ensure future generations will always know Samuel Miller’s story and the reasons why this generation believed that it was no longer appropriate to have his name synonymous with community worship.”

This decision somewhat parallels a 2021 decision by Wake Forest University to rename one building in its chapel complex while retaining the name of a former slaveholder on the chapel itself as an intentional reminder of complex legacy.

At Wake Forest, Wait Chapel is named for Samuel Wait, the school’s first president, who was a slaveholder, as were his three successors, including Washington Manly Wingate, the fourth president. In May 2021, Wake Forest University President Nathan Hatch announced that trustees had voted to remove Wingate’s name from a building attached to Wait Chapel but to retain the chapel name.

Wingate Hall was renamed “May 7, 1860 Hall” in memory of the 16 slaves bequeathed to Wake Forest College from the estate of Baptist layman John Blount and sold on that day, with Wingate’s approval.

Of retaining the chapel name, Hatch explained: “We acknowledge the inherent contradictions that summon our intellect and moral conviction. The complexity and contradictions create a tension that invites engagement with our story and the people whose lives are remembered and honored.”

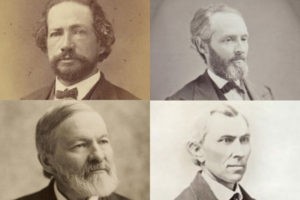

Southern Seminary founders, clockwise from top left: Boyce, Manly, Williams, Broadus.

The flagship seminary of the Southern Baptist Convention, meanwhile, has declined to remove the names of slaveholding founders from its buildings.

Al Mohler, president of Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Ky., said he and the trustees determined that just as the Bible retains the names of imperfect, sinful leaders like Abraham, Moses and King David, so the seminary should do with the names of James P. Boyce, its first president, and founding faculty members John Broadus, Basil Manly Jr., and William Williams.

Concerned alumni and Southern Baptist pastors had called on the seminary to remove the names of Boyce, Broadus, Manly and Williams from campus buildings.

Southern Baptist Theological Seminary is one of the nation’s largest seminaries, with more than 4,000 students. Its student body is 87% white, 6.6% international students, 2% Black, 1.7% Asian, and 1% Hispanic.

Princeton Theological Seminary, the second-oldest seminary in America, is a more average-size seminary, with about 360 students. The student body is 64% white, 10% international students, 9.7% Black, 7% Asian, and 5% Hispanic.

Related articles:

Princeton Seminary’s gift of reparations? Let’s talk instead about cultural competency | Opinion by Wendell Griffen and Lauri Umansky

Naming and un-naming: Slavery, schools and the present moment | Opinion by Bill Leonard

Southern Seminary won’t rename buildings but creates scholarships for Black students

What to do if you unearth a history of slavery in your church, college or institution?