Prophecy is a big deal within the world of American nondenominational Christianity. I’m not talking about the kind of application of apocalyptic biblical texts to current events that Hal Lindsay and Tim LaHaye made popular back in the day. No, our latter-day prophets receive messages straight from God. And the messages they receive relate to all the burning concerns of the day, everything from the winner of the World Series to the next American president.

Alan Bean

America’s new crop of Christian prophets unanimously predicted a Trump victory. Given their social location, it is hard to imagine them predicting anything else. But they were wrong. And that’s a problem.

Jeremiah Johnson, a Christian prophet who gained notoriety in 2015 by correctly predicting a Trump victory in 2016, has apologized to his followers for getting it wrong in 2020. Johnson probably would have been OK if he had ignored his mistake or blamed the unexpected outcome on election fraud. But he was up-front about it.

“I was wrong. I am deeply sorry, and I ask for your forgiveness,” he told his fans. “I would like to repent for inaccurately prophesying that Donald Trump would win a second term as the president of the United States.”

The result of his confession, inevitably, has been an avalanche of hate mail and death threats.

What is prophecy?

When I was in seminary in the late 1970s, my professors told me that biblical prophecy wasn’t about predicting the future. Prophets like Elijah and Jeremiah, they said, were all about “speaking truth to power.” Prophecy, we were taught, is more about “forthtelling” than “foretelling.”

That was way too simple.

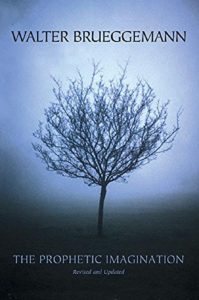

Walter Brueggemann’s 1978 book, The Prophetic Imagination, sent a seismic shock through the world of Christian theology. Whenever the gap between God’s unrelenting purpose and realities on the ground became intolerably immense, the Old Testament professor said, the prophets offered Israel an alternative future, conjured through the power of sanctified imagination.

Walter Brueggemann’s 1978 book, The Prophetic Imagination, sent a seismic shock through the world of Christian theology. Whenever the gap between God’s unrelenting purpose and realities on the ground became intolerably immense, the Old Testament professor said, the prophets offered Israel an alternative future, conjured through the power of sanctified imagination.

I have seen this kind of prophetic ministry up close and personal.

A lesson from Mariah

Fifteen years ago, I was working full time as director of Friends of Justice but was contemplating a return to pastoral ministry. Then I got a call from a Black Cajun woman named Ann Colomb who, along with three of her sons, had been charged with running a massive crack cocaine ring out of their modest FHA bungalow.

We met in the lobby of one of the big hotels in the French Quarter and retired to the nearest McDonald’s. Ann was traveling with her daughter, Jennifer Price, and Mariah, her 4-year-old granddaughter. While Nancy kept Mariah entertained, Ann and Jennifer showed me the five binders of legal documents their attorneys had given them.

Ann Colomb

The federal prosecutor told Ann he would let her off if her boys would plead guilty. She laughed in his face. “We didn’t do none of this,” she told me, “and I’ll be damned if I’m gonna send my boys to prison on a lie!”

It soon was obvious that none of the 30-odd government witnesses possessed actual knowledge of the Colomb family. Most of them couldn’t even get the name right. There is no parole in the federal legal system, but inmates facing long sentences can win time cuts by snitching on their friends. It was a system ripe for abuse. I told Ann she needn’t worry. No federal prosecutor would take facts this flimsy to trial.

When I discovered I was wrong, I cancelled vacation plans and drove the 725 miles to Louisiana. Each day, I would make the drive from Church Point to the federal courthouse in Lafayette with Ann and her family. Every evening, I would blog about the case and make calls to local news agencies. When the jury handed down a conviction, Ann, Danny, Sammy and Edward were taken into custody. Their families collapsed in horror and disbelief.

A month later, I was visiting with the Colomb clan in Church Point, hoping against hope that this legal travesty could be righted. When little Mariah asked me to read her a story, I found an illustrated children’s Bible and turned randomly to a family friendly rendition of Joseph and Potiphar’s wife. The picture showed the hero languishing in prison.

“Who’s that?” I asked, pointing to Joseph.

“That’s Jesus,” Mariah told me. “He’s in jail with my granny, and God’s gonna get them out.”

“That’s Jesus,” Mariah told me. “He’s in jail with my granny, and God’s gonna get them out.”

Mariah was quickly proved right. A federal inmate had been brought to Lafayette for the trial but wasn’t needed. He had assumed that Ann and her boys were guilty until he read my blog posts and conversed with two of Ann’s sons behind bars. Realizing that Ann’s boys didn’t fit the drug dealer profile, the inmate told the judge that neither he, nor any of the other witnesses, knew anything about Ann and her sons. He had participated in perjury parties, he said, in which identifying information on the defendants was passed from witness to witness. Everybody wanted a piece of the action.

A special hearing was quickly scheduled, the jury verdict was vacated, and, on a sweltering hot summer’s day, Ann and her boys walked free.

Imagining an alternative future

How could little Mariah anticipate these developments when I couldn’t? She saw no visions. She had no special word from the Lord. But she knew her granny didn’t belong in prison and that God wouldn’t stand for it. Instinctively, she imagined an alternative future where the crooked was made straight and all flesh beheld the glory of the Lord.

Biblical texts, Brueggemann explains, “are acts of imagination that offer and propose ‘alternative worlds’ that exist because of and in the act of utterance.” They don’t just say what’s going to happen next; they make it happen.

William Blake

William Blake arrived at a similar conclusion late in the 18th century. In The Marriage of Heaven and Hell, the painter-poet informed his readers that, just the other night, “the prophets Isaiah and Ezekiel dined with me.” Since childhood, Blake had been given to vivid visions in which he conversed with ancient worthies from Elijah to Shakespeare. So, he may have described a mystical encounter. More likely, the conversation was merely a poetic device.

Prophetic speech, Brueggemann says, “must be imaginative because it is urgently out beyond the ordinary and the reasonable.” If it sounds absurd, “it is an absurdity that may be the very truth of obedient imagination.”

“I was persuaded, and remain confirmed, that the voice of honest indignation is the voice of God.”

Blake asked his dinner guests how they “dared so roundly to assert that God spake” to them. Isaiah, by Blake’s account, freely admitted that he neither heard nor saw God. “But my senses discovered the infinite in everything, and I was persuaded, and remain confirmed, that the voice of honest indignation is the voice of God.” Therefore, the prophet explained, “I cared not for consequence but wrote.”

The gap between the real and the ideal was so huge that God had to be outraged.

Does believing make it so?

Blake voiced the obvious objection: “Does a firm persuasion that a thing is so, make it so?”

“All poets believe that it does,” the prophet answered. “And in ages of imagination this firm persuasion removed mountains.” Unfortunately, in Blake’s day, “many are not capable of a firm persuasion of anything.”

Ezekiel agreed with Isaiah’s account.

Last week, Ann Colomb passed into the eternal mystery while her husband, James, was fetching her a cup of coffee. The family is grieving, but they also rejoice that Ann was able to live out the last 15 years of her life with the family she loved. So, did young Mariah bring about her gramma’s release by uttering her prophetic word?

Maybe. How would I know?

What we know about the unknown

In his 1910 book on Blake, G.K. Chesterton argued that when we limit the regions of truth to what can be objectively verified, we are “turning the key of the madhouse on all the mystics of history. You cannot take the region of the unknown and calmly say that, though you know nothing about it, you know all the gates are locked. We do not know enough about the unknown to know that it is unknowable.”

“If we are firmly persuaded that the God of Jesus lives, all bets are off.”

But if we are firmly persuaded that the God of Jesus lives, all bets are off. The word of prophecy becomes not only possible but appropriate; not merely appropriate, but necessary.

In the preface to the second edition of The Prophetic Imagination, Brueggemann envisions a day when real flesh-and-blood churches will function as “prophetic subcommunities” set against the flagrant injustice and numbing consumerism of our time. But that can’t happen, he cautions, apart from “a shared willingness to engage in gestures of resistance and acts of deep hope.”

And this kind of “evangelical will for public engagement,” demands a new kind of pastoral leadership.

An example in Fort Worth

Fortunately, men and women are stepping forward to point us in the needed direction. Thanks to the prophetic leadership of pastor Ryon Price, Broadway Baptist Church in Fort Worth, Texas, has created an ACT council. ACT stands for “acknowledge, confess, transform.” We acknowledge our complicity, historical and present, in systems of sin. As we confess, we are transformed into prophets.

“Jesus taught his disciples to pray that God’s kingdom would come ‘on earth as it is in heaven,’ the church’s website reminds. “At Broadway we pray and we work for the hope of heaven come near. We invite you to pray and work with us.”

William Blake spent most of the hundred years after his death disparaged as a crackpot. But since 1916, his most famous poem, “Jerusalem,” has evolved into the unofficial national anthem of Great Britain. “I will not cease from Mental Fight,” Blake declares, “nor shall my sword sleep in my hand, ’til we have built Jerusalem in England’s green and pleasant land.”

As an appendix, Blake quoted Numbers 11:29: “Would that all the LORD’s people were prophets, and that the LORD would put his spirit on them.”

May it be so!

Alan Bean serves as executive director of Friends of Justice, an alliance of community members that advocates for criminal justice reform. He lives in Arlington, Texas.