Achieving racial reconciliation can be hard work and often slow, but Christians are called to pursue it relentlessly, said speakers at a summit of Baptists seeking to bridge a racial divide that continues to bedevil the nation.

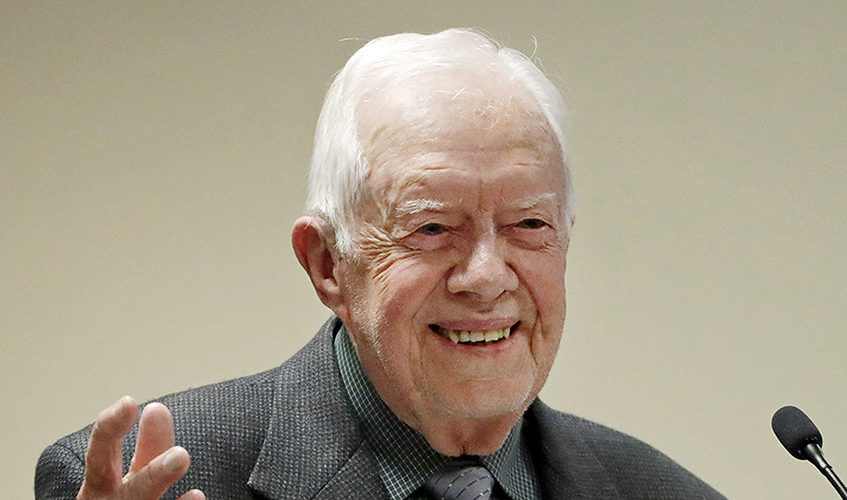

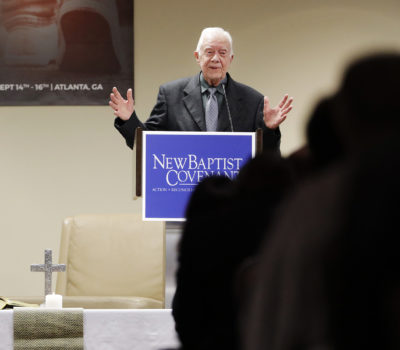

Former President Jimmy Carter joined national religious leaders in Atlanta for the New Baptist Covenant summit Sept. 14-16, urging participants to challenge a “resurgence of racism.”

“The New Baptist Covenant can be a powerful potential weapon to set an example not just among Baptists and among churches, but in communities and among people of all faiths,” said Carter, who lent his support to the organization’s beginning in 2007 and convened its first meeting. “I hope that we can set an example to the world. Accept my personal thanks for what you are doing to maintain momentum that exists and increase its impact.”

The NBC was created to unite Baptists of different races, which it has fostered with a series of gatherings and summits. The three-day meeting in Atlanta highlighted emerging partnerships between predominantly black and white congregations working in their communities to address racial and social justice.

Framing the message at the Atlanta summit was what many there saw as a resurgent racism which followed a brief burst of optimism after the election of the nation’s first black president. The killings of black men and women by police, the disproportionate percentage of blacks incarcerated in U.S. prisons, the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement, and a volatile presidential campaign all lent a sense of urgency to the meeting.

Former President Jimmy Carter says some white Americans stay quiet when they see racism or discrimination, fearful of losing a “position of privilege” in society. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

“We’ve seen a resurgence of racism in our country,” Carter said. “Because of Martin Luther King Jr. and President Lyndon Johnson, we had begun to breathe a sigh of relief in the 1970s. We thought, we’ve finally resolved the racial issue. After the civil rights movement was successful, schools were integrated. We thought we could stop worrying about it.

“But in the last few years we’ve seen a resurgence.”

Carter, now 91 and a lifelong Baptist, expressed embarrassment at the presidential campaign between Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump. But he also said he was confident in the nation’s “beautiful mosaic” of races and religions and in its past resilience in the face of division.

“I think there will be a positive reaction after this election,” he asserted. “I pray it will come out a certain way, but I think there will be a lot of lessons learned. And I think the average person now will be looking at how to do better things, how to have a superb American policy on peace and human rights and other aspects of life. I think we’ll raise our standards as a public and I believe our next president will accommodate that inclination.”

Echoing Carter’s concerns was Traci Blackmon, acting executive minister of justice and witness for the United Church of Christ. A well-known speaker on race and religion, Blackmon offered a pastoral presence in Ferguson, Mo., following the fatal police shooting of black teenager Michael Brown in 2014.

“It often seems like justice can take forever. But we cannot give up. We cannot quit,” she said.

Prayer is an essential component in the struggle but is most effective when we “pray with our feet,” Blackmon said, quoting the 19th-century social reformer and abolitionist Frederick Douglass: “I prayed for freedom for 20 years, but received no answer until I prayed with my legs.”

“God so desires our obedience and cooperation that God is unwilling to carry out God’s purposes until men and women have energized and honored their participatory role in their own prayers,” she said.

“I am not suggesting that work and prayer are the same thing. Work is not a substitute for prayer. They are not to be equated but neither are they to be separated. Prayer must include the obedience of one’s conviction and a willingness to seek that which is good and just. Dormant prayer must not be a substitute for action.”

Blackmon said those advocating for racial justice could take hope in a parable found in the Gospel of Luke describing an unjust judge who neither feared God nor respected people, but who nevertheless granted justice to a widow who persisted until she received it. Though the text explicitly says the judge never “changed his heart or mind,” the widow’s dogged persistence effected a change in his behavior.

Traci Blackmon says racial reconciliation often appears to be a slow process, but Christians cannot give up on the task. (BNG photo)

“The Voting Rights Act didn’t pass because of changed hearts and changed minds but because righteousness prevailed,” she said. “Let me be clear that when it comes to the lives of those I fight for in the streets, I’m not concerned about changing your heart but changing your behavior. On Sunday mornings your heart is my concern, but on the streets I want to change your behavior. Your heart is welcome to join you.”

Over the past year, the New Baptist Covenant has encouraged “covenants of action” between congregations as vehicles to pursue racial reconciliation. Pastors of three pairs of congregations described their efforts at the summit, including one between Friendship-West Baptist Church and Wilshire Baptist Church, both in Dallas.

“In our journey of thermostatic two-ness we are out to transform the world,” said Frederick Haynes, senior pastor of predominantly black Friendship-West Baptist. “Jesus has sent us out two-by-two to stand up against structures of injustice.”

George Mason, senior pastor of the mainly white Wilshire Baptist, added: “This two-by-two thing is important. It’s about bringing our stories together. The American story is not one story. We want to make it one story, but in doing so, we deny the story of another. We need a two-narrative ecclesiology about the white church and the black church discovering one another.”

The two churches have engaged in pulpit swaps and choir visits and have collaborated to combat predatory lending in Dallas.

“It is clear we can be faithful to Christ’s vision of beloved community only when we walk side-by-side, have each other’s backs and go on this journey together,” Mason said.

Other “covenants of action” highlighted in Atlanta were First Baptist Church and First Baptist Church of Christ in Macon, Ga., and First Baptist Church and Providence Baptist Church, both in Greensboro, N.C. Also reporting on their covenant were the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship of Oklahoma and churches representing Native American tribes in the state.

This year’s summit was an opportunity for the diverse group to share stories and experiences as well as engage in sometimes difficult conversations, said Hannah McMahan, executive director of the New Baptist Covenant.

“Through the stories of others we are seeing pieces of the Kingdom of God that we have never known,” said McMahan. “The spirit of the Lord is upon us and God has anointed us for this time and this place. Under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, when we come together we can change the world.”

— With reporting by Carrie McGuffin, assistant communications specialist for the Cooperative Baptist Fellowship.