Earlier this summer, the United States Supreme Court ruled in a 5-to-4 decision that private religious schools should have the same access to public funds as private “nonsectarian” schools. Chief Justice Roberts’ majority opinion cited the Constitution’s protection of the free exercise of religion as a justification for allowing religious schools access to public funds available to private, non-religious schools.

The decision went against the reasoning of the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty, which argued in an amicus brief that the use of public money for religious schools too closely entangles government and religion. BJC contended that prohibiting the public funding of religious institutions, including those responsible for religious education, protects “the distinctiveness of religion” and promotes “values that advance religious freedom.”

The decision is likely seen as a “win” for Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos, who has spent much of the past three years working to advance programs that benefit private schools, including a proposed $5 billon federal tax credit that would fund scholarships to private schools and other educational programs. Secretary DeVos pitched the tax credits as benefiting “America’s forgotten children, who will finally have choices previously available only for the rich.” Framing such programs as an attempt to level the economic playing field sounds good in theory, but in reality, these programs bolster an educational system built upon a legacy of racism and white supremacy.

Protestant Christians like Secretary DeVos, who grew up in the Christian Reformed Church, have not historically been advocates of private religious schools. The support for private education among Protestants in the United States developed quickly in the wake of mid-20th century desegregation as white families sought to keep their children in white schools.

Catholic origins

The public school system in the United States emerged in the early 19th century with a strong bias toward Protestant Christianity. Historian Tracy Fessenden’s work Culture and Redemption: Religion, the Secular, and American Literature shows that 19th century Roman Catholics contended “state-run schools were instruments of a de facto Protestant establishment.” While the Constitution may have prohibited the establishment of religion, it did not mean the country always lived up to such standards.

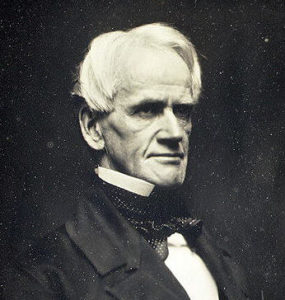

Horace Mann

Protestants argued that the public school system did not favor one sect of Christianity over another, characterizing public education as “nonsectarian.” Educational reformer Horace Mann incorporated the King James Version of the Bible into the curriculum to provide a general Christian education without focusing on any particular doctrines that might privilege one denominational group over another. Alternatively, public schools prohibited the use of the Douay Bible, used by Roman Catholics, as being too sectarian.

In selecting the King James Version of the Bible, however, the public school system already staked out its territory as a Protestant institution. The edition of the KJV accepted for use in the public schools, Fessenden writes, included a dedication that “referred to the pope as the ‘man of Sinne’” and a preface that “refuted the legitimacy of the Catholic Church.”

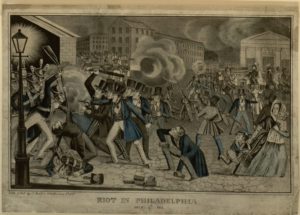

Catholics in Philadelphia in the 1830s and ’40s fought the Board of Controllers of the public school system to make exceptions for Catholic students to no avail. Such requests only further emboldened the voices of anti-Catholic Protestants. In May 1844, the tension between Protestants and Catholics in the city boiled over into what became known as the “Bible Riot,” which resulted in a number of churches and homes being destroyed by arson and at least 17 people killed. Such was the backdrop of the founding of Roman Catholic private institutions as an alternative to the public education for Catholic students.

As Roman Catholic institutions emerged across the country, Americans worried that public money might go to fund these overtly sectarian institutions. While the public education system, with its Protestant proclivities, was far from perfect, it had aspirations of being nonsectarian. Public money used for overtly sectarian reasons would violate the Establishment Clause of the Constitution.

As Roman Catholic institutions emerged across the country, Americans worried that public money might go to fund these overtly sectarian institutions. While the public education system, with its Protestant proclivities, was far from perfect, it had aspirations of being nonsectarian. Public money used for overtly sectarian reasons would violate the Establishment Clause of the Constitution.

In 1875, increasingly worried about the possibility of public money going to private sectarian schools, Rep. James G. Blaine of Maine proposed an amendment to the Constitution to explicitly prohibit the use of public money for sectarian purposes. While the amendment failed, numerous states across the country passed versions of the so-called “Blaine Amendment” within their state constitutions to protect public money from being used for religious training and education. Today these Blaine Amendments continue to exist in many states.

When Protestants started schools

For much of American history, the matter of private, sectarian education has been a Roman Catholic issue. Increasingly in the second half of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century, however, newly founded Protestant schools have complicated the issue.

Despite the longstanding Protestant privilege within America’s system of public education, two factors led to the growth of Protestant support for private education alternatives. The first, the Supreme Court decisions in Abington v. Schempp (1961) and Engel v. Vitale (1962) prohibiting mandatory Bible readings and state-sanctioned prayer in public schools, respectively. Prior to these rulings, however, was the slow and delayed implementation of Brown v. Board of Education (1955) mandating the integration of public schools across the country.

Arkansas soldiers from the 101st Airborne Division escort African American students to Central High School in Little Rock in September 1957, after the governor of Arkansas tried to enforce segregation. (Photo courtesy National Archives)

Many churches stood at the forefront of delaying the integration of the public school system. Shortly after the “Little Rock Nine” integrated Central High School in Little Rock, Ark., the Baptist Joint Committee’s Report from the Capital reported that Baptists in Little Rock, “continue their efforts to provide education for children out of schools closed due to efforts to avoid integration.” The governor had closed Little Rock’s public high schools for an entire academic year.

Whether the reactions of local Baptists favored integration or segregation depends on one’s perspective. Ouachita Baptist College, which did not accept Black students until 1962, began operating an all-white high school out of First Baptist and Second Baptist churches in Little Rock. Ralph Phelps, president of the college, wrote in the Biblical Recorder that this action should be seen as favoring neither integration nor segregation, even though the school admitted only white children. Among his reasons cited: “The Baptists of Arkansas who own and operate Ouachita have not desegregated in their churches and have not authorized the college to do so.” (Another view of this event is given by a former pastor of Second Baptist Church in Little Rock.)

Although Baptist High in Little Rock was short-lived, the pressures facing these churches were not an isolated trend. Across the American South, churches became part of a larger development of private education alternatives for white children to avoid integration. According to the Southern Education Foundation, a nonprofit committed to “advancing equitable education policies and practices that elevate learning for low-income students and students of color in the Southern states,” private education grew dramatically in the period after Brown v. Board of Education.

“From 1950 to 1965, private school enrollment grew at unprecedented rates all over the nation, with the South having the largest growth,” according to the SEF. As the number of private schools grew nearly 130% in the South between 1950 and 1965 and 90% in the rest of the United States, legislatures in the South moved to block and delay the integration of public schools to varied levels of success.

Creating ‘Segregation Academies’

Some of the private schools that emerged in South have been termed “Segregation Academies” and many of them are still in existence today. While Segregation Academies like Indianola Academy in Mississippi are not all explicitly “religious,” when Indianola opened in 1970, students met in the school’s satellite campus in a Baptist church.

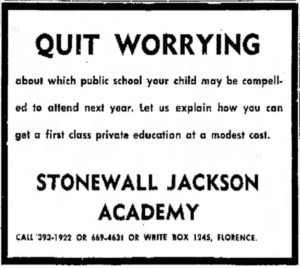

A 1970 advertisement for a segregation academy appealed to parents who were concerned about desegregation busing.

While some of these academies have sought public funding as “nonsectarian” schools, other private institutions emerging in the mid-20th century embraced a conservative Protestant identity. The Association of Christian Schools International, for instance, formed in 1978 when multiple regional school associations joined together. The ACSI now serves 24,000 schools in more than 100 countries. The international identity of the organization today obscures the more nefarious and racist reasons that led to the rise of private Protestant education in the first place.

Many of these private schools now justify their existence to offer an alternative to the “liberalism” taught within the public school system. This pivot emerged in the 1970s as the Internal Revenue Service threatened to revoke the tax-exempt status of private schools that discriminated on the basis of race. Bob Jones University tested the constitutionality of the IRS’s policy at the Supreme Court and lost in 1983. So long as religious schools sought to keep their tax-exempt status, they could not formally engage in racial discrimination. Today, under the banner of combatting liberalism and propagating conservative Christian values, many of these schools remain predominantly white.

The present moment

The year of our pandemic 2020 may prove to be a pivotal moment in the history of American public education. As President Trump and Secretary DeVos demand public schools physically reopen this fall or risk losing federal funding, they put an already underfunded system in jeopardy.

Public education reflects — and has reflected for more than a century and a half — a collective effort on the part of our country to educate the future generation. As the pandemic strains our ability to collectively combat a deadly and infectious virus, it similarly strains our country’s collective educational project.

More than 50 million students attend public schools, compared to less than 6 million students in private schools. With questions swirling around whether or not schools can reopen in the fall, now is the perfect time and perhaps a pivotal time to reinvest in public education rather than create avenues for a few students to attend private schools founded in an effort to resist racial integration.